There seems to be an emerging global trend of overtly corrupt leaders strengthening their vice-like grip on power, whether with electoral backing or not. Similar stories are being heard in Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Italy, China, North Korea and Russia, and the overlapping patterns are becoming increasingly difficult to ignore.

Cobbling together coalitions

“It is a sign of how deeply the 42-year-old former Prime Minister Matteo Renzi foundered in his bid to infuse fresh life into Italian politics that the 81-year-old, scandal-plagued, four-time former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi looks on track to succeed him as Italy’s political comeback kid,” writes the New York Times on current Italian politics.

Berlusconi’s coalition is headed by Nello Musumeci, who failed to secure an outright majority. Sicily will face a hung parliament if he doesn’t do so. But, as the NYT points out, “cobbling together coalitions to win elections is not the same thing as delivering stable governance.”

Mr. Berlusconi’s coalition includes the anti-immigrant Northern League party and the right-wing Brothers of Italy party. “In addition, Mr. Berlusconi — who is barred from holding office because of a 2013 fraud conviction — has made it clear that he is the real power behind the coalition.”

Within the larger European context, this situation poses a problem. A hung government “is a fate economically struggling Italy, on the front lines of Europe’s migrant crisis, can ill afford next spring. And it would make it harder for President Emmanuel Macron of France and Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany, whose hand is weakened following German election results in September, to hold together an already shaky union.”

An incorruptibly early election

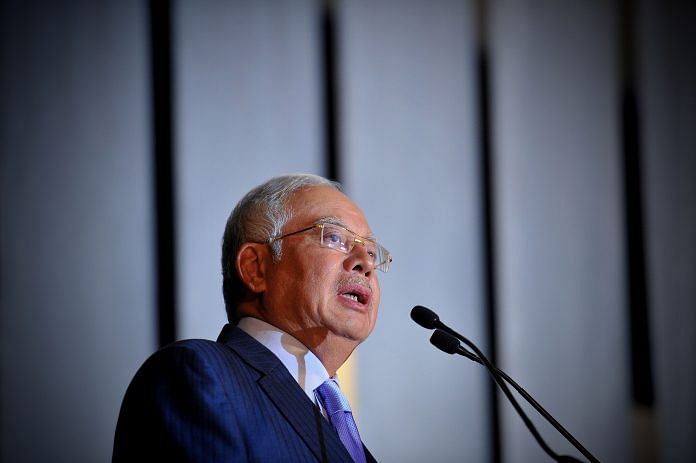

The Malaysian Prime Minister, Najib Razak, looks ready to call – and win- an election, writes The Economist.

Despite being deeply implicated in embezzlement two years ago, Mr. Najib has worked assiduously to bury it, while purging opponents and distracting voters. “Mr Najib does not dispute that roughly $700m entered his personal bank accounts shortly before the previous election, in 2013. But he says it was a gift from an unnamed Saudi royal, and that most of it was returned.”

“Confronted with a strengthening opposition, Mr Najib might choose to hold the election sooner, rather than later. But a vote in the next two months would probably coincide with seasonal flooding in rural areas, which might both suppress the vote and make the voters who do turn out irritable. A short delay could avoid this. But the prime minister will not want to wait for long.” This is because Anwar Ibrahim, a leader of Pakatan Harapan (PH), an opposition coalition, is currently in jail for sodomy, on flimsy evidence. Given that Mr Anwar may walk free from April, Mr Najib looks ready to call the election now.

The Rich and Mighty

“There are countries in which you are accused of an act of corruption and then you are arrested. And then there are countries in which someone decides to arrest you and only then are you called corrupt,” writes Anne Applebaum in the Washington Post.

She places Saudi Arabia in the second category, where Mohammad bin Salman used the excuse of corruption to arrest several people.

“In China, Trump’s new friend, President Xi Jinping, has used charges of “corruption” in a strikingly similar manner. As in Russia and Saudia Arabia, almost everyone in the nepotistic Chinese ruling class has extraordinary access to money, jobs and even state assets. The decision to call anyone “corrupt” is just as political in Beijing as it is in Riyadh. Since taking power, Xi has, like Putin, used that tool to eliminate political rivals, to scare his colleagues and to establish himself as the unchallengeable ruler. And by using the language of “anti-corruption,” he, like Putin, seeks public approval in a society that is well aware that the system is skewed against them.”

But Applebaum points out that Western democracies like the United States of America shouldn’t be left out of the narrative. “But Trump is also part of the story. By his own example — through his disdain for courts and for the media, through his scorn for ethical norms — Trump has cast doubt on the Western model. He may even have encouraged the Saudi prince more directly. Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law, a living embodiment of American nepotism, visited Riyadh for long talks — officially to promote Mideast peace, but perhaps business and politics came up, too — in the days before the arrest.”

The Dictator’s Standard Operating Procedure

In Saudi Arabia, Mohammad bin Salman seems to applying what Fareed Zakaria for the Washington Post terms as the “new standard operation procedure for strongmen around the world”.

Drawing parallels with Putin’s rise to power and following similar trajectories in China, Turkey and the Philippines, Zakaria points out that “Leaders have taken to using the same ingredients — nationalism, foreign threats, anti-corruption and populism — to tighten their grip on power.”

“Classic centralized dictatorships were a 20th-century phenomenon — born of the centralizing forces and technologies of the era. They maintain the forms of democracy — constitutions, elections, media — but work to gut them of any meaning. They work to keep the majority content, using patronage, populism and external threats to maintain national solidarity and their popularity. Of course, stoking nationalism can spiral out of control, as it has in Russia and might in Saudi Arabia, which is now engaged in a fierce cold war with Iran, complete with a very hot proxy war in Yemen.”

Zakaria also zooms out to a more global picture, and admits that “in countries such as India and Japan, which remain vibrant democracies in most respects, there are elements of this new system creeping in — crude nationalism and populism, and increasing measures to intimidate and neuter the free press.”

On the warpath

Donald Trump’s stance on North Korea has always been controversial. After taking on a softer tone at the start of this week, Trump once again made a confrontational speech on Wednesday that reinforced the course that he has set—”a strategic momentum that, left unchanged, stands a growing chance of leading to war,” writes Evan Osnos in the New Yorker.

Osnos writes that Washington seems to be grappling with the idea of waging a preventive war now rather than a larger war later, much like the situation in 2002. “Faced with that kind of choice, there is a temptation to think that, by attacking first, America could more easily define the scope and the consequences.”

“The Trump Administration has succeeded more than most observers expected in pushing China to squeeze North Korea, through the use of sanctions and financial restrictions. That strategy deserves more time to bear fruit. The alternative to war is diplomacy and pressure, and, at the moment, that option is urgently in need of a stronger lobby in Washington.”