We live in a world where the “end of history” is being redefined in ways dramatically opposite to how it was conceived two decades ago. Stalinism is ominously taking root in the world, and omissions of history would have us believe that communist sympathisers are romantics, not fanatics. Yet, is there anything really unprecedented about this era? Or are we, like past generations, taken over by “the parochialism of the present”?

Communist sympathisers aren’t romantics. They’re fools.

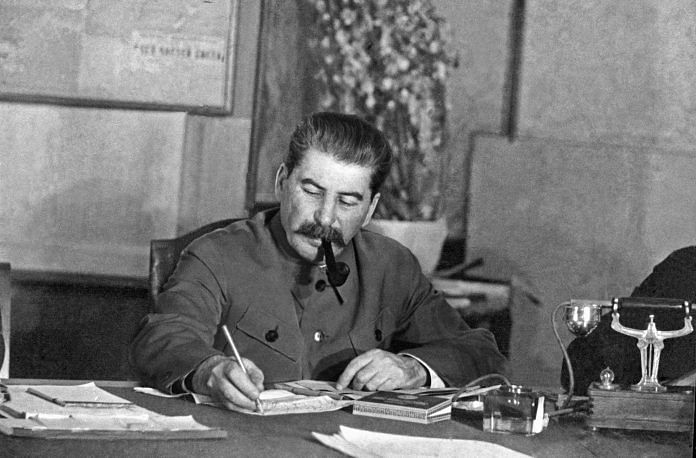

Too many of today’s progressives remain in “a permanent and dangerous state of semi-denial about the legacy of Communism a century after its birth in Russia,” writes Bret Stephens in The New York Times. The worst bit, he argues, is that “we treat its sympathisers as romantics and idealists, rather than as the fools, fanatics or cynics they really were and are.”

“They will insist that there is an essential difference between Nazism and Communism — between race-hatred and class-hatred; Buchenwald and the gulag — that morally favours the latter. They will attempt to dissociate Communist theory from practice in an effort to acquit the former. They will balance acknowledgment of the repression and mass murder of Communism with references to its “real advances and achievements.” They will say that true communism has never been tried. They will write about Stalinist playwright Lillian Hellman in tones of sympathy and understanding they never extend to film director Elia Kazan.”

“It’s a bitter fact that the most astonishing strategic victory by the West in the last century turns out to be the one whose lessons we’ve never seriously bothered to teach, much less to learn. An ideology that at one point enslaved and immiserated roughly a third of the world collapsed without a fight and was exposed for all to see. Yet we still have trouble condemning it as we do equivalent evils.”

Putin’s omissions of history

While nobody, not even Putin, knows what the future holds for Russia, few people in Russia’s elite expect the succession to happen constitutionally or peacefully, argues a piece in The Economist. And that’s partly why Putin wants Russia to forget the Revolution.

“But perhaps another reason Mr Putin is so reluctant to recall the overthrow of the ancien régime is because he has modelled himself on its rulers,” it says.

“There is little doubt that Mr Putin will be reaffirmed as Russia’s president after the election next spring. But his victory will only intensify the talk of what comes afterwards. The point of the election is not to provide an alternative to Mr Putin, but to prove that there is none. And yet it is not just a formality. Although the tsar is not accountable to any institution, he is sensitive to public opinion and ratings. These are closely watched by opportunistic elites.”

Navalny, Putin’s main challenger, is dangerous for Putin even though he can’t beat him. What he offers is “not just a change of personality at the top of the Kremlin, but a fundamentally different political order—a modern state. His American-style campaign, which includes frequent mentions of his family, breaks the cultural code which Mr Putin has evoked. His purpose, he says, is to alleviate the syndrome of ‘learned helplessness’ and an entrenched belief that nothing can change.”

A Chinese ‘end of history’

Stalinism of the 21st Century is ominously taking root is China, writes Jackson Diehl in The Washington Post, and it will have consequences for the rest of the world.

“Twenty-five years ago, the liberal democratic system of the West was supposed to represent the ‘end of history’, the definitive paradigm for human governance. Now, Xi imagines, it will be the regime he is in the process of creating,” he writes.

“Of course, it is possible that Xi is overreaching. As it watches the United States and much of the rest of the West struggle with populist and nationalist movements, the political consequence of the last crisis of capitalism, the Chinese elite may overestimate the attraction of their totalitarian alternative. Centralised control of society and the stifling of individual freedom led China and other Communist nations to catastrophe in the late 20th century; Xi’s bet that a modified, technologically updated system can work in the 21st century could easily fail.

It would nevertheless be dangerous not to take China’s strongman seriously. He is imagining a world where human freedom would be drastically curtailed and global order dominated by a clique of dictators. When a former chief political adviser to the U.S. president applauds that ‘adult’ vision, it’s not hard to imagine how it might prevail.”

Our parochialism of the present

Are we really in an era of unprecedented instability, as pundits and politicians, would have us believe? Or are we just ignorant of history, asks Tom Switzer in The Sydney Morning Herald.

“When people place too much emphasis on what seems to be relevant to the here and now, and fail to put contemporary events in a broader historical context, they are giving in to what the influential University of Sydney philosopher John Anderson called ‘the parochialism of the present’.”

“Is today’s emerging regional terrain more volatile than the late 1940s and 1950s when our leaders faced the challenges of decolonisation, communism and Asian nationalism? What about the 1960s when south-east Asia was the most unstable and violent region in the world? Or when the Cold War world was poised on the knife-edge of a nuclear disaster?”

“How about the late 1960s when Britain withdrew its military presence from east of Suez and President Richard Nixon warned that US allies would assume responsibility in money and manpower for their security?”

“Remember the late 1980s and early 1990s when we were told that the fall of the Berlin Wall and collapse of Soviet empire heralded ‘the end of history’?”

“Is today’s strategic uncertainty more volatile than the early 2000s when the September 11 and Bali terror attacks apparently marked the beginning of a new era? The world, we were told, would never be the same again.”

“Bear all this in mind when you hear people insist we are living in the most uncertain era of international relations in living memory. As the Greek philosopher Heraclitus said: ‘All is flux, nothing is stationary’.”

Asia awaits Trump – with trepidation

As Asian governments await the arrival of Donald Trump, they do so with trepidation. What’s got most American allies worried is the US drift and Chinese expansion, writes Michael J. Green in Foreign Policy.

“Previous populist presidents, from Bill Clinton to Barack Obama, developed their real Asia strategy only after seeing how their campaign rhetoric looked to leaders in the region. As a general rule, Trump does not get high marks for listening, but that will be the most important part of his visit to the region,” he writes.

“U.S. partners are growing alarmed that the president’s hostility to trade agreements may be as intense in practice as it was in campaign rhetoric. The U.S. withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership was probably the greatest self-inflicted wound on American regional influence since the Vietnam War. Asian business leaders have confidence in the American economy, and investment from Japan, South Korea, and Southeast Asia into the United States is robust. But the United States has ceded leadership on regional economic rule-making, and China is grabbing the helm.”