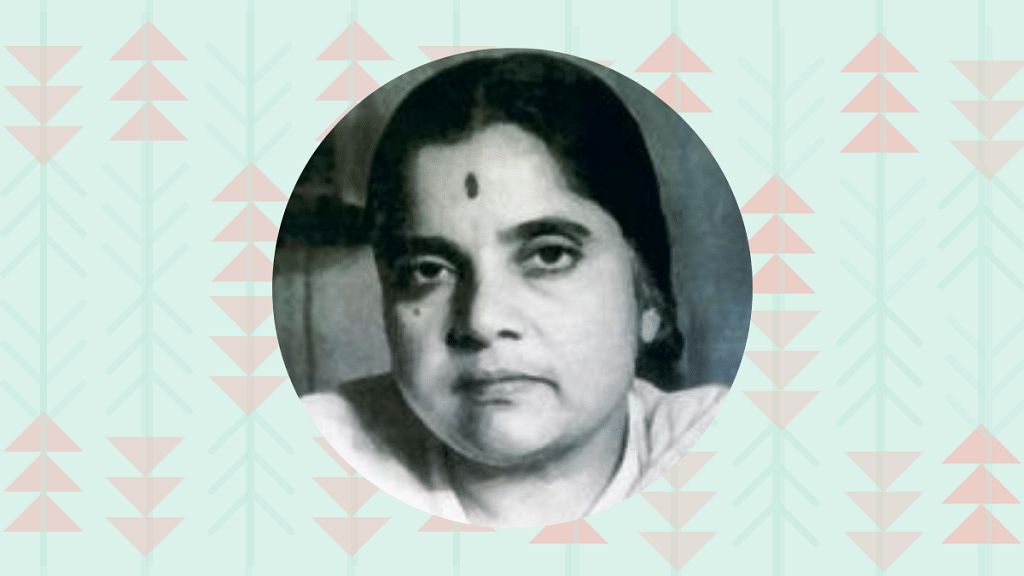

Durgabai Deshmukh, one of 15 women in the 299-member Constituent Assembly, was a feisty individual who studied law to help the wrongfully convicted.

New Delhi: If there is one thing you must know about Durgabai Deshmukh, among a handful of women in India’s Constituent Assembly, it is that she was astonishingly brave.

In 1921, when she discovered Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi would be visiting her hometown, Kakinada in present-day Andhra Pradesh, she swiftly began making arrangements for him to visit the devadasis, or prostitutes, and Muslim women in her village so that he might enlighten them.

India was under British rule at the time, and an initiative like this could have got her arrested. But a staunch Gandhian herself, and unafraid of the consequences, she managed with great difficulty to find a venue, raise money, and negotiate with the organisers to secure five minutes of the Mahatma’s time.

She was all of 12 years old.

This strong sense of justice — one premised on giving the marginalised their due — defined all her subsequent contributions to the country, as well as her life at large.

Born on 15 July 1909, Durgabai grew up in poverty, and inherited a sense of selfless service at a young age. Describing an episode from her childhood in her autobiography Chintaman and I, she wrote:

“Few would volunteer to carry the bodies of those who had died of plague or cholera, and ambulances were unknown. My father, along with three of his friends, used to be the pall-bearer.

“Though the streets of Kakinada were deserted, my father would take my mother and the two children (including Durgabai) to the church, the mosque, or the burning ghat to show us how the bodies were disposed of, perhaps with a view to making us courageous enough to face the inevitable event of death.”

Moments of courage in Durgabai’s life are countless. At age eight, she was married to a rich zamindar. But by 15, before the marriage was consummated, she had decided she wanted to opt out.

Also read: Sardar Hukam Singh, a minority rights champion in Constituent Assembly

On terms she herself negotiated with her husband, Durgabai freed herself from the marriage.

When her father died and her mother faced a tonsure in keeping with the customs of the time, Durgabai’s fierce protests ensured she was spared the ritual.

As a young volunteer for a khadi exhibition in pre-Independence India, she refused to let Jawaharlal Nehru, then a senior Congress leader, into the grounds without a ticket, forcing him to turn away.

Freedom struggle

Durgabai’s introduction to Hindi propelled her into the freedom struggle. In six months, she learned Hindi, and began running teaching centres with the help of her mother to spread the nationalist cause.

However, in the Constituent Assembly debates, it wasn’t Hindi she championed, but Hindustani, saying, “The national language of India should not be and cannot be any other than Hindustani which is Hindi plus Urdu.”

She added that those who opposed her suggestion be accommodating “in the interests of the minorities here who, like the Muslims, need time and sympathy to adjust themselves”.

In 1930, she was arrested for participating in the ‘Salt Satyagraha’, and jailed for two years. During this time, she shared cells with women convicted of various crimes, and even those who were wrongfully convicted.

Also read: The Kerala governor who openly pushed Indira’s case for PM

“I had then decided to take up the study of law so that I could give such women free legal aid and assist them to defend themselves,” she wrote. And thus she studied law, and was accepted into the Madras bar in 1942.

Constituent Assembly

As a member of the Constituent Assembly, Durgabai emerged as a staunch advocate of a free judiciary.

“The independence of the judiciary is a thing which has to be decided and this independence to a large extent depends on the way in which these judges are to be appointed,” Durgabai said in one of the Constituent Assembly debates.

“They should not be made to feel that they owe their appointment either to this person or that person or to this party or to that party,” she added. “They have to feel that they are independent.”

Durgabai served as a member of the Committee for Rules and Procedure and the Steering Committee, both of which held sway on how the country’s Constitution could be changed in the years to come.

In total, Durgabai recalled having moved approximately 750 amendments, on her own as well as in collaboration with other assembly members.

“I made it a point to attend every sitting of the Constituent Assembly and also of the Congress Assembly Party which was held almost every alternate day in the Constitution House,” she wrote in her memoirs.

Dedication to service

The title of Durgabai’s autobiography refers to her second husband, Chintaman Deshmukh, the suave first governor of the Reserve Bank of India whom she married in 1953 and spent the rest of her life with. Deshmukh was the finance minister of India at the time.

Their wedding was a frugal affair, with Nehru as first witness. The next day was business-as-usual for Durgabai and her husband, where she set off for famine relief work in Pune and he for budget preparation.

“I am afraid of remaining inactive,” Durgabai wrote towards the end of her biography, “because I know that when one has nothing to think of, many bad ideas surround one and dance in one’s idle mind.”

Durgabai’s endurance is startling in the face of her struggles, and especially under her circumstances as a woman from a lower middle-class household. But that never stopped her.

“Life is uncertain and the life-span is limited. Why, then, wait to do a good thing?” she wrote.

Durgabai passed away on 9 May 1981.