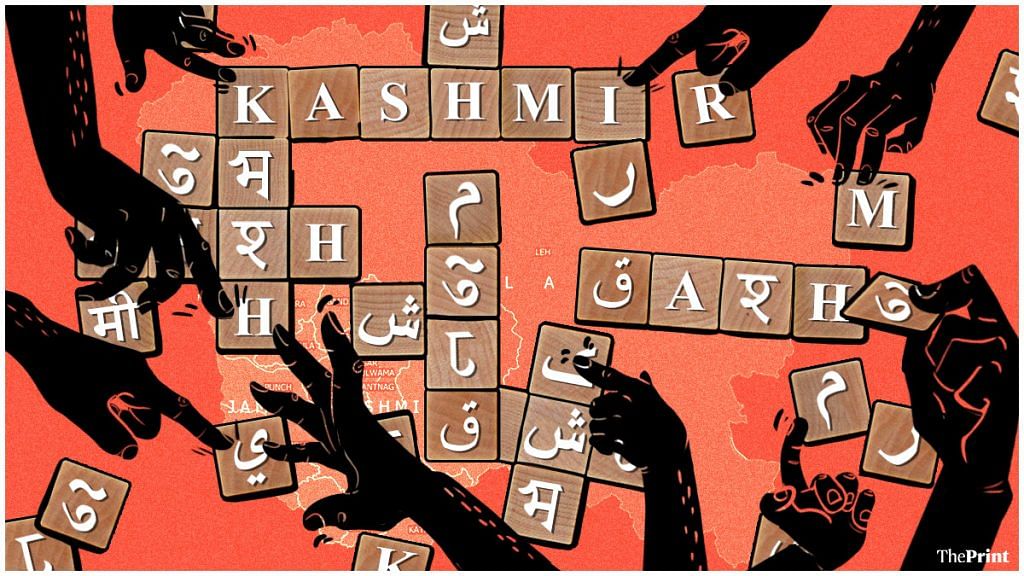

Srinagar/New Delhi: A quiet cultural conflict is underway in Kashmir. Although rooted in the Hindu-Muslim divide, it has yet to rouse ire and outrage nationally. The strife over which script the Kashmiri language should be written in — Devanagari or Nastaliq — fuels the dreams and hopes of those who communicate in it.

The idea of two scripts took root after the exodus of Kashmiri Pandits in the early 1990s from the Valley, but the debate has gathered momentum only in recent years. Kashmiri Hindus want Devanagari to get an official stamp and are demanding that it be declared as a co-script for the language. Muslims, who have been using the Perso-Arabic Nastaliq script to transcribe the language for centuries, see it as yet another assault on their identity.

In 2020, the Narendra Modi government passed the Jammu and Kashmir Official Language Act, making Kashmiri, Dogri and Hindi the official languages of the Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir, in addition to English and Urdu. That Hindi was given official status caused some unease among non-Hindi speakers of the UT. The government also ordered a validation of Kashmiri written in Devanagari in the digital repository of the Common Locale Data Repository.

The fact that Kashmiri has been reduced to a battle between two scripts has caused much consternation among scholars. Eminent linguist Braj B. Kachru, who passed away in 2016, was of the view that the literary culture of Kashmiri developed over the centuries in two vital contexts of contact — cultural and linguistic. “These two types of interactions have not always been harmonious or indeed welcome,” he wrote in his 2003 paper ‘The Dying Linguistic Heritage of the Kashmiris’.

Within the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir, including Ladakh, Urdu remains predominant. “Kashmiri is spoken only in the Kashmir Valley, a little bit in Chenab valley, as well as Jammu. In the state of J&K, we have a variety of languages: Dogri in Jammu Balti and Ladakhi in Ladakh, Pahadi in the west, Punjabi among the Sikhs of Kashmir. The main language of communication for the people of this state has been Urdu,” said Mohammed Amin Bhat, president of the Adbi Markaz Kamraz, a 50-year-old cultural and literary organisation in Kashmir at the forefront of preserving the language.

Also read: Pashmina takeover, debt traps—Kashmir’s dying handwoven carpet industry hurts Pasmandas most

Displacement spurs the debate

The exodus of Kashmiri Pandits encouraged them to begin writing Kashmiri in Devanagari, the script used for languages like Hindi and Marathi. “It’s not like Kashmiri Pandits haven’t written in Perso-Arabic [Nastaliq] earlier. There were a lot of Hindu scholars in Perso-Arabic, but things changed after the 1990s. Once we migrated out of Kashmir, the main language outside was Hindi, not Urdu. We then developed an appropriate script for Devanagari, which is as good as the Persio-Arabic script,” said Arvind Shah, a Kashmiri Pandit writer.

Arvind Shah gave the example of writer Ratan Lal Shant, who became a strong advocate of writing Kashmiri in Devanagari after 1990. “He changed his stance after the migration. Our children didn’t have exposure to Urdu after the migration. For them, we needed to transcribe Kashmiri into Devanagari.”

According to Arvind Shah, many Kashmiri Hindu scholars continue to write in Nastaliq and then transcribe their work in Devanagari. “As Devanagari in Kashmiri does not enjoy an official status, writers are unable to apply for grants or awards if they use that script,” he said.

Also read: You know ‘The Kashmir Files story’ of BK Ganjoo. Now know his neighbour Abdul’s

Can two scripts coexist?

Linguistic disputes, especially between Hindus and Muslims, are not uncommon in India. The strife between Hindu and Urdu, in fact, can be traced to the pre-Independence era. Kashmiri, at present, is undergoing a somewhat similar contention. In the 2017 book The Changing Language Roles and Linguistic Identities of the Kashmiri Speech Community, published by Cambridge University Press, M. Ashraf Bhatt wrote that Kashmiri originally did not have a prescribed script.

Hindus and Muslims have differing views on the origin of the Kashmiri language too, he added. Hindus are of the view that Kashmiri has close links to Sanskrit, while Muslims trace the ancestry of Kashmiri to a Dardic language — a subgroup of Indo-Aryan languages natively spoken in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Gilgit-Baltistan in present-day Pakistan. “Kashmiri carries the uncertainty of not having its own alphabet because of certain religious, political and historical ideologies and biases. This may create differences between the two communities (Hindus and Muslims), and may defame the centuries-old binding force, the root of Kashmiriyat and its pluralistic values–the Kashmiri language itself,” wrote Bhatt.

Kashmiri Pandit scholars argue that both scripts can, in fact, co-exist. Arvind Shah said the co-existence of Devanagari and Nastaliq does not divide the language on religious lines. “If Kashmiri written in Devanagari gets official status, it will only benefit the language and enhance its number of readers. It won’t cause any harm in any way,” he said.

Roop Krishen Bhat, editor of magazine Vaakh, concurred, adding that they are not demanding that Nastaliq be eradicated but for Devanagari to be a co-script for the Kashmiri language.

Devanagari has the sanction of the All India Kashmiri Samaj, an apex body of various Indian and overseas Kashmiri Pandit organisations. The body argues that by officiating the use of Devanagari, Kashmiri will benefit a generation of Kashmiri Pandits who have been deprived of creative contact with their mother tongue.

Also read: Modi govt’s rehabilitation of Kashmiri Pandits fell flat. They’re strangers in their own land

‘Division on religious lines’

However, there is vehement opposition to the idea that Devanagari can bring Kashmiri Pandits back into the cultural fold. Mohammed Amin Bhat, president of Adbi Markaz Kamraz, a cultural and literary organisation in J&K, says the introduction of the script will lead to a religious divide. The organisation’s former secretary, Mir Tariq Rasool, told the Kashmir Observer in a 2020 interview that the promotion of Devanagari is part of the larger plan “to boost Hindu chauvinistic political narrative.” He adds, “It will damage the etymological fabric of the Kashmiri language because a huge chunk of words cannot be fitted in the Devanagari script.”

Imran Nabi Dar, state spokesperson of the National Conference, called the order for the validation of Kashmiri written in Devanagari in the Common Locale Data Repository another assault on his “Kashmiri identity”. “Why issue an order for validation of Kashmiri language in Devanagari Script in J&K when Urdu still is the official language? Is this not another assault on our identity?” he tweeted.

Why issue an order for validation of Kashmiri language in Devanagari Script in J&K when Urdu still is the official language? Is this not another assualt on our identity? pic.twitter.com/wyKiXQEh2N

— Imran Nabi Dar (@ImranNDar) August 28, 2020

One language, many scripts

Kashmiri has evolved over hundreds of years, embracing many scripts either long forgotten or in disuse. The oldest known script was Sharda, which evolved from Brahmi nearly 1,200 years ago when Kashmiri was still developing as a language.

A language that lends itself to poetry, Kashmiri’s beauty in the Sharda script is best evident in the shayari composed by the first Kashmiri poet, Lal Ded or Lalleshwari. The script was used and inscribed even on Muslim gravestones, some of which can be spotted at the Makhdoom Sahib Shrine in Srinagar today.

Even after the establishment of the Kashmir Sultanate by the Shah Mir dynasty in the late 14th century, Sharda remained in use. For a time, Arabic too was written in the Sharda script under Kashmir’s eighth sultan, Zhiyas-ud-Din Zain-ul-Abidin. But its dominance gradually waned, as it gave way to the calligraphic style of Nastaliq, which is defined by short verticals and long horizontal strokes. And yet, many books in Kashmiri were written in the Sharda script till as late as the 19th century.

Over the years, Sharda gradually lost its patronage in the Valley. Until the rise of the Rajput Dogra dynasty in Kashmir in the 19th century, Persian was the lingua franca of Kashmir, after which the baton was passed on to Urdu, which was also written in Nastaliq.

While upheavals in the Valley changed the contours of society through the centuries, Kashmiri remained the language of communication. It received no state patronage but borrowed from all the ‘great’ languages, including Persian, Arabic, English, and Punjabi.

Also read: You know ‘The Kashmir Files story’ of BK Ganjoo. Now know his neighbour Abdul’s

Kashmiri in modern India

Post-Independence, the Kashmiri language has had a tenuous journey. It was never the language of elites and did not enjoy the status of ‘official language’ in its own home. It wasn’t taught in schools as a language until recently. In modern India, two generations of Kashmiris have been robbed of the right to study their mother tongue in schools.

From 1947 to 1953, Kashmiri was taught in schools as an official language. However, in 1953, when Sheikh Abdullah was arrested, the language was suddenly dropped from the course. It didn’t return to school textbooks until the early 2000s. “When they imprisoned us, they put our language in jail,” said Professor Shaad Ramzan, Sahitya Akademi Award winner and former Head of Department of Kashmiri Language in Hazratbal University. “Nehru used to say, if you want to finish a people, kill their language. He did the same to Kashmiris, they wanted to oppress us, so repressed our language,” he added.

A certificate course in the Kashmiri language was introduced only in the early 1970s at the Srinagar campus of Jammu and Kashmir University. In 1975, the Department of Kashmiri was formed in the University of Jammu and Kashmir, and in 1984, it was introduced as a degree course in colleges. By early 2000s, it was introduced in schools as a compulsory course till Class 8. “There was a method to this madness of introducing a postgraduate course first and then trickling it down to school level,” said Amin Bhat, “We needed teachers first so that they could teach Kashmiri.”

Currently, there’s a gaping hole in the Kashmiri language curriculum: it’s not taught in Classes 9 and 10. “This is the State’s ignorance. They make general Urdu teachers teach Kashmiri till Class 8. For classes 9 and 10 they’d need subject-specific teachers, hence are not teaching the language in these two standards,” Prof. Ramzan said.

Amin Bhat claimed the state had told their organisation the integration of language in the curriculum would need Rs 100 crore and 8-10,000 teachers.

However, without a concerted effort to revive the language and the script, there are fears that it will be lost to future generations.

(Edited by Rachel John)

Clarification: A quote by writer Arvind Shah was inadvertently attributed to Roop Krishen Bhat, the editor of Vaakh. ThePrint regrets the error.