Amazon Prime Video’s Cinema Marte Dum Tak is an ode to the 90s pulp movies like Gunda (1998). Created by Vasan Bala and co-directed by Disha Rindani, Xulfee and Kulish Kant Thakur, the six-part docu-series stars four ‘B-grade’ star makers.

Directors of the 90s, J Neelam, Vinod Talwar, Dilip Gulati and Kishan Shah are given the opportunity to revisit their glory years by making short films. “I didn’t have a star cast. I had to make the poster a raunchy one so that I could attract the audience,” says Vinod Talwar. The butt of memes today, films made by the four directors had the audience wolf-whistling. They also made the box office go ka-ching at the time.

Full of sleaze, terrible, catchy, double-meaning dialogues and raunchy songs, these films had an audience, as pointed out by journalist Kunal Shah in the first episode of Cinema Marte Dum Tak. Back then, the audience wanted to watch films about dacoits, dangerous beauties and dungeons, according to Shah. Most kids born in the 1990s have watched these movies at least once.

Also read: That ‘90s Show gives comfortable old-timey sitcom vibes. But it lacks punch of original

A jungly ride

The series is structured in a kitschy style, much like the films it looks at. It is entertaining, evokes sentiments and also explores an era that now exists in dilapidated, shut-down cinema halls in various cities. Stuck with low budgets, these directors made films that were entertainers and ran housefull shows in shady halls. The revisiting is almost like dusting cobwebs and equal parts funny and poignant. It is like watching an encyclopaedia of these films coming alive on screen.

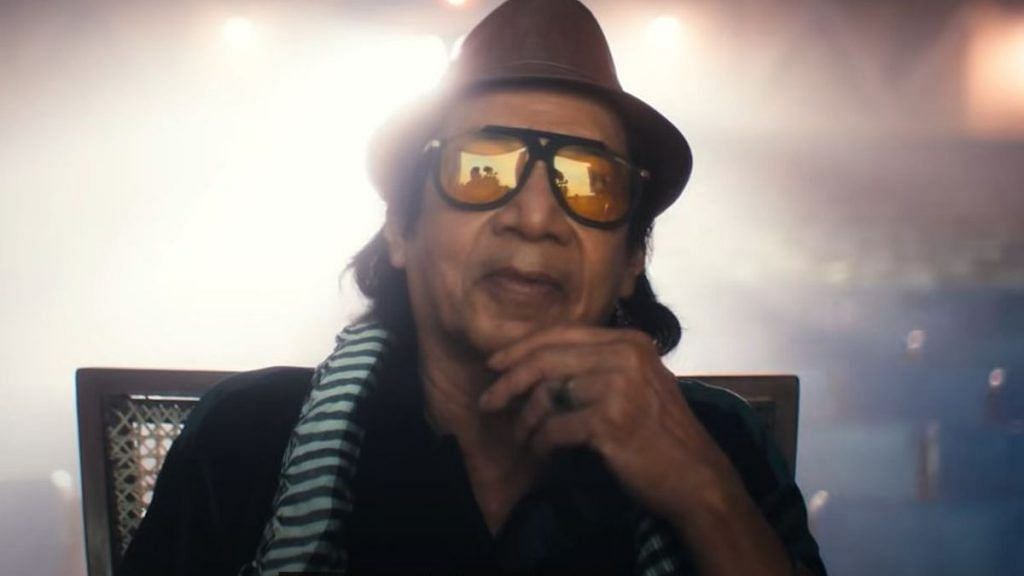

Creator Vasan Bala previously made Monica O My Darling (2022) as a nod to such movies, albeit in his signature style. The new series features the ‘heroes’ of such films, including Raza Murad, Mukesh Rishi, and Harish Patel. There is also a special appearance by Arjun Kapoor.

The episodes are also named like the subject of the series—in true ‘B-grade’ movies style, from Haath ki safai to Seene mein cinema. As the directors talk directly to the camera, we also get a glimpse of their craft. Their working style, how they scout locations and even the dialogue-writing. The research work that went into creating the show deserves special mention.

The four filmmakers have made the new short films using their tried, tested and once ‘hit-maker’ methods with no compromises to their vision. The final products are Shanti Basera, Blood Suckers, Sautan Bani Chudail and Jungle Girl.

Also read: Authentic and brilliant, The Test 2 is the cricket documentary we’ve all missed

A class or grade issue

The docu-series traces the demise of the industry that eventually became thinly disguised pornographic movies. Ultimately, the most radical aspect of the series is that it finally takes away the blanket of judgement these films have met, especially by ‘high-brow’ filmmakers and moviegoers and even film journalists who did not consider these films good enough to write articles about, except with disdain. Ultimately, it is a long and hard look at the existing classism within filmmaking. And how it ascribes titles like ‘B-grade’ or ‘C-grade’ to these movies.

Films made purely for the entertainment of the low-income class were not considered good enough to even have Wikipedia pages. The class conflict is also shown through people-actors, dubbing artists and technicians, for whom it was just a job, a means for providing for their families and ensuring a good future for their children.

From the women actors to distributors, everyone faced the consequences of being associated with these films. But in the hands of the series’ directors, a mirror is held up to show the real ‘dirty minds’. The people who created a demand for these films, or the ones who secretly loved watching them would also go around saying that such films ‘corrupt’ people.

The series finale has a director’s round table, akin to the ones organised by many film journalists these days. It finally gives a well-deserved space that the four directors never got. It is the most fitting ending.