A pile of wood enshrouding a dead woman’s body, a crowd of people, and one flaming torch — it’s a visual we have seen all too recently, splashed across our social media feeds, newspapers and TV channels. In Hathras, the crowd consisted of policemen who hurriedly cremated the allegedly gangraped Dalit woman’s body in the middle of the night without the family present, but in the film Aakrosh, a gangraped Adivasi woman’s family was able to conduct the final rites. The person who lights her pyre is her husband, who has been wrongly accused of her murder, and the police, although present, stand quietly in the back.

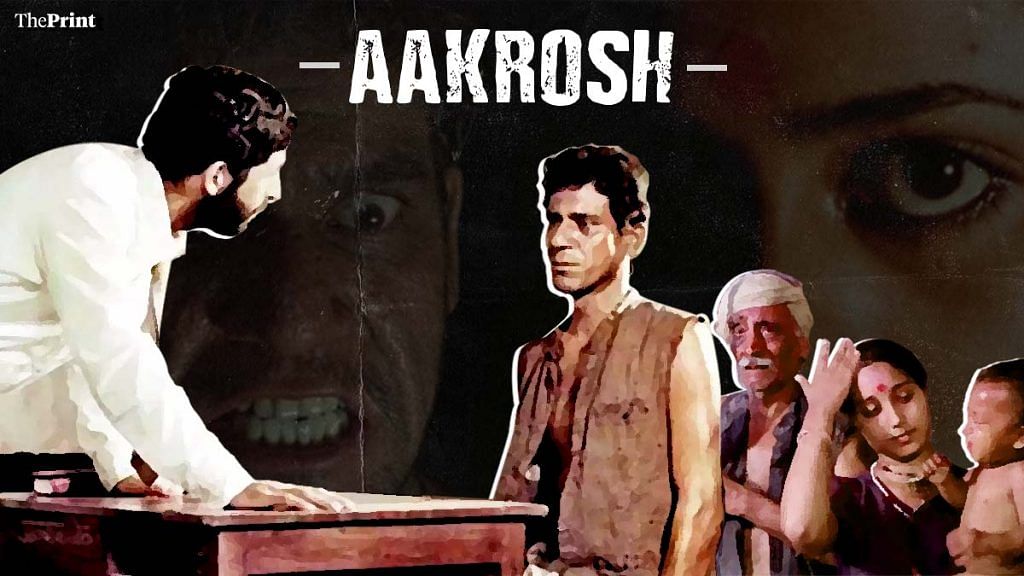

It’s a jarringly prescient visual to see in a movie that was made in 1980, and it is made all the more powerful thanks to Om Puri and his silence. He utters barely a few words in the entire film, yet he is its very soul. Even though Naseeruddin Shah won the Filmfare Best Actor award for this film, and Puri won for Best Supporting Actor, it is the latter’s haunted, hunted eyes, anguished twitches and eventually, one enraged, tortured, chilling scream, that stay with you long after the film has ended.

In an interview, director Govind Nihalani, who debuted with this film, said, “Om had lived [his character] Bhiku’s story by the time this scene [the scream] was shot and empathised with him completely. I just told him I did not want his expression to be either neutral or over-emotional and then left it to him. I don’t know what he did to build himself up, but Om’s screams touched me like they did each viewer.”

Shah, in his memoir, And Then One Day, wrote: “Om’s blazing salt-of-the-earth intensity finally caught the eye of many a film-maker but it was Govind Nihalani who first recognized the magnetic simplicity in his screen presence and cast him in Aakrosh as the anguished silent Adivasi, wrongly accused of his wife’s murder, Om’s definitive film performance.”

In the week of the late Om Puri’s 70th birth anniversary, ThePrint goes back to the film that was one of the actor’s defining roles.

Also read: Article 15 takes off on Badaun, Una cases, stirs debate on depiction of trauma in Bollywood

The complex web of politics, gender & oppression

Aakrosh is set in a small town in Maharashtra that is ruled by a nexus of powerful local politicians, police and various henchmen. It begins with the funeral of Nagi Lahanya (Smita Patil), who jumped into a well after she was gangraped by some of the most powerful people in the town as revenge for her husband Lahanya Bhiku’s (Om Puri) refusal to turn a blind eye to their corrupt ways. They frame Lahanya as her murderer.

The nervous Bhaskar Kulkarni (Naseeruddin Shah) is his government-appointed lawyer, while the prosecutor is a man named Dusane (Amrish Puri), a man who believes wholly and solely in the power of proof, even though everyone knows that in a case like this, proof is impossible, with the raped woman dead and witnesses being bought, threatened and assaulted every day.

Dusane also straddles the complicated life of being an Adivasi himself, but one who is able to hobnob with the town’s VIPs with ease. Yet he faces harassment, too, with nightly phone calls reminding him that no matter what he does, he will remain an Adivasi.

In an interesting exchange, Bhaskar, his former junior with whom Dusane shares a warm relationship (at least Bhaskar thinks so), says that this is his first big case since going independent, and he’s worried that if he loses, people will think he lost deliberately because he is a Brahmin and wanted to send an Adivasi to the gallows. Dusane responds that if Bhaskar wins (not that he’ll let him, he laughs), people will think Dusane lost on purpose to save the life of his fellow tribesman.

Most of the film’s dialogue is spoken by these two characters, but all the while, throbbing in every frame, is Lahanya’s silence. There are only a couple of scenes in which he speaks, and those are in flashback. It is as if, ever since he heard his wife’s screams as she was being gangraped and he could not help her, he has been rendered mute by the horror and helplessness and by the knowledge that if he speaks, he endangers his younger sister, his infant son and his elderly father.

His and his family’s refusal to speak frustrates Bhaskar, who keeps telling him that if he doesn’t talk, no lawyer can help him. What Bhaskar, well-meaning though he is, doesn’t seem to understand is that his impatience for the “pathetic” silence of “these people” highlights his own lack of empathy for their predicament. When a social worker in the area tells him, “You want them to speak when they aren’t even allowed to breathe”, Bhaskar dismisses it as Marxist claptrap, but somewhere, he is unsettled by this harsh truth.

Also read: Vinod Khanna’s Achanak is a philosophical look at the duty of medical and legal professionals

A difficult yet masterful film to watch

Part social commentary, part thriller, the film features liberal use of long pauses, chases, slow-burning suspense, shadows, and close-ups of Om Puri’s face as he sinks into his memories of Nagi, of his own violence towards her, of her eyes, of their intense lovemaking.

Aakrosh is not an easy watch. The silences are deliberately oppressive, the songs are deliberately deployed to heighten the tension. In many films, songs are used to lighten the mood. But Nihalani, in this masterful, National Award-winning film, uses songs for a different purpose. Here, the music is not meant to lighten, but to underline a mood. Whether it is the sombre vocals of the opening credits or the upbeat song accompanying the lavani dance at which the town’s elite make crass remarks about the dancer, every note has meaning.

And finally, at the end, at another funeral, when Lahanya, fearing that in his absence, his sister will suffer the same fate as his wife, does something so unthinkable and so horrific, you want desperately to close your eyes, to shut out what you just saw. But force yourself to watch — because in the discomfort of the viewer lies the victory of this film.

Also read: A Suitable Boy is my response to India’s disappearing pluralism, Mira Nair says