Ghaziabad: About 20 people sway and pray in front of a cross studded with red lights that flash nonstop in Ghaziabad’s Shalimar Garden. Chants of ‘praise be the Lord’ fill the room. But the room is in a nondescript building that looks nothing like a church. It’s sandwiched between a salon and a kitschy marriage hall. It has no signboard, no Christian iconography on the outside.

This anonymity is deliberate and convenient. It keeps the growth of the Pentecostal church in Ghaziabad under the radar.

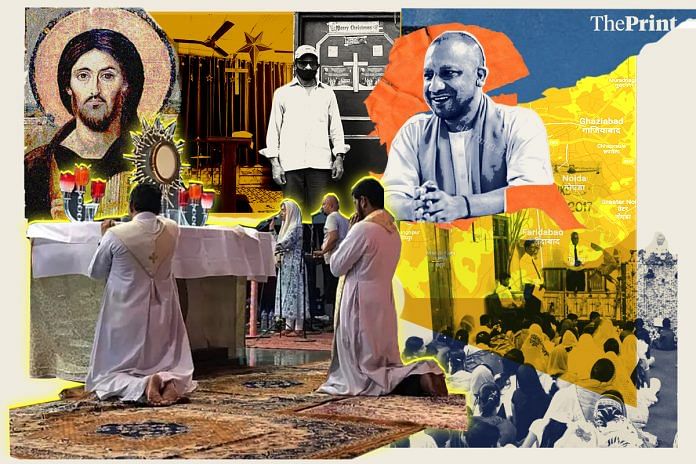

But after Hindu groups complained this month, the Ghaziabad Police arrested a Pentecostal pastor and his wife for allegedly converting people. Police claim to have identified other pastors as well, fuelling fear and rumours in Ghaziabad’s Christian community.

“We don’t want people to know the church’s location,” says Sunil Phillip Swami, the pastor of this congregation. “The idea is for God to guide them to us whenever they are in search of peace and solace.”

The same undercurrent of caution is palpable among the growing Pentecostal Christian community across NCR. In February, about 80 churches from around the country including the United Pentecostal Church-North East India held a protest in New Delhi over rising attacks on the Christian community.

Also Read: Christianity in India wasn’t always imposed. Just look at its Portuguese art

Punjab to Tamil Nadu to Delhi-NCR

For years, Punjab has been in the spotlight with reports of rising numbers of Charismatic and Pentecostal Christian churches, decades after their rise in Tamil Nadu. A similar unnoticed trend could now be playing out in Ghaziabad and the rest of Delhi-NCR as well.

“There are around 40-45 Pentecostal churches in Ghaziabad and most of them have come up in the last eight to ten years,” says Meenakshi Singh, a Protestant Christian activist who participated in the February protest.

But with no survey or official data, it’s all anecdotal estimates. The fact that many churches operate out of unmarked homes or rented spaces adds to the lack of information.

Much like the church buildings, new Pentecostal converts are all hard to identify. They inhabit the two faiths and cross over and back quite seamlessly. Entering the Pentecostal fold is easy, the gate-keeping isn’t very rigorous. The new members are not required to change their Hindu names or ways. Some members in Ghaziabad have both — Hindu gods and the cross — hanging on the walls of their homes.

But with rising Hindu anxieties over religious conversions, fuelled by groups like the Bajrang Dal, local police scrutiny will only deepen.

Uttar Pradesh, under CM Yogi Adityanath, is the first state to have bought stringent anti-conversion law under The Prohibition of Unlawful Conversion of Religion Act.

“There are some people with deceitful mindsets who carry out religious conversions, but we have to work together to stop them,” Adityanath had said at Banjara Kumbh in January.

As per an Indian Express report, nearly 100 people including pastors have been booked for religious conversion attempts in Uttar Pradesh, which Christian groups say are false cases. They accuse the police of not conducting any investigation and “simply arrest[ing] people, creating an atmosphere of terror”.

Rising number of Christians

In the narrow bylanes of Seemapuri, a Delhi locality bordering Ghaziabad, an increasing number of households are turning to Christianity but the outward markings are missing, that is until you reach the house of Ram Singh. A golden cross and a Merry Christmas sticker stands out on his brown-red door. Right next to it is a big board giving information on a yogshala.

A retired seaman in the Indian Navy, Singh, 75, converted to Christianity 30 years ago. Known as “Daddy”, Singh is not a priest but local people follow him for his teachings on Christianity and Yoga. He and a local Hindu saint Bablunath organise yoga sessions every Sunday in a local park.

“I am a Christian and a Hindu too. It’s hard to let go of your roots,” smiled Singh.

Singh was introduced to Pentecostal Christianity by his wife Devi, who had met a nun at the hospital where she worked as a sanitation worker. The nun had assured Devi that Christ would change the mind of her husband and he will no longer abuse or beat her up.

After Singh started going to church he stopped drinking alcohol and abusing his wife, he claimed.

Singh said that his was the first family to convert to Christianity. Twenty-five other households have turned to Christ today, he said.

Some Hindus in the neighbourhood are sitting up and taking note.

“The number has risen in the last five to six years. Every time a converted Christian comes to buy property from me, I try to make them understand but they instead ask me to convert,” said Sanjay Verma, 45, a property dealer.

There is an organised counter-action to re-convert them as well. Ghar wapsi (homecoming) campaign has reached Ghaziabad.

Praveen Kumar of Bajrang Dal said that newly converted Christians often say that Jesus transformed their lives and rid them of their illnesses. He even filed a police complaint in February against Santosh John and his wife Jiji. He calls their claims of miraculous cures a “lie”.

According to Kumar, he has conducted ‘ghar wapsi’ of five such people.

“Most of those who convert are poor,” he claimed.

Also Read: Cure cancer, undo death: Punjab’s Christian ‘prophet, pastors’ offer miracles, compete with deras

Sunday service

Binu Johnson, a pastor of another Pentecostal church in Ghaziabad says he receives requests from 40-50 non-Christians every month for help with illnesses. A few approach him because they are convinced that an “evil” spirit has entered their body.

“I just ask them to come to the church and pray to Jesus—nothing else. And when their prayers are accepted, they start following the Lord. We don’t force or allure them. They are sent by Jesus to us.” said Johnson.

Both Charismatic and Pentecostal churches are fast-growing religious movements not just in India but around the world, and are characterised by their emphasis on faith-healing, speaking in tongues and other manifestations of the Holy Spirit.

“We don’t convert people. People come to us with their problems and through Jesus, they find the solutions. And if they ask us to get them closer to Jesus, how can we deny that? Is that conversion? We are not forcing anyone,” Phillip Swami said, placing his hand on the head of a congregation member who was touching his feet.

As some of the younger worshippers start playing the drums and keyboard stacked on one side of the hall, the rest of the parish wave their arms in praise and worship, while Phillip Swami leads them. “Jesus is with you,” he shouted, to the resounding replies of Hallelujahs.

Sunday service has begun.

Praise and worship in these churches are an exuberant explosion of emotions—joy and supplication, celebration and desperation. People plead and pray for mercy, healing, forgiveness and fulfilment. It’s a far cry from the restrained liturgy in most traditional churches in India.

“Praise be to the Lord,” Prince greeted his pastor Phillip Swami. He started attending service at the church ten years ago. He was raised by a “wealthy Gujjar family” who adopted him from an orphanage when he was a toddler, but he is no longer in touch with them.

Just last year, he married Geeta, a member of the church from the Valmiki community. She too started attending church around the same time as Prince in 2014. Their love had blossomed over Sunday congregations.

But neither Geeta nor Prince wanted to discuss the arrest of pastor Santosh John and his wife. Other congregation members, too, said they knew nothing about it.

On 1 March, John and Jiji were arrested and booked under the Uttar Pradesh Prohibition of Unlawful Conversion of Religion Act 2021, based on a complaint by a Bajrang Dal member who accused them of converting people to Christianity.

The couple, originally from Kerala, was picked from their residence in Indirapuram. They are currently lodged in the district jail. Investigating officers claim that the evidence collected so far points to the pastor being a part of “group involved in conversions”.

“We have also zeroed in on a few more pastors and other people involved in this, and they will be summoned soon,” said Swatantra Singh, ACP (Indirapuram).

Caste and cures

Two years ago, Tez Bahadur, 52, converted to Christianity along with his family after he was ‘cured’ of his illness. Bahadur, who was born in the Jatav caste, couldn’t walk properly and that’s when he went to the local church.

“I was cured within a month after which I reopened my paan shop,” he says. But his Hindu neighbours say that there was no “magic”, and that he received money for medical treatment.

Bahadur who has a tattoo in praise of Goddess Durga on his right arm is one of several new Christians who attend Sunday prayer without shedding their Hindu identity.

“Pentecostal Christians don’t have any elaborate way of conversion. Attend a mass or two, recite some hymns, buy a bible and you are converted. You don’t even have time to process the conversion. There is no baptism involved,” said AC Michael, coordinator of United Christian Forum, a Delhi-based society of Christians.

“It will take two and three years to become a Christian in a Catholic church,” he added.

Most of the attendees in the three Pentecostal churches that ThePrint visited in Ghaziabad were Dalits, or people from marginalised communities and lower-income groups.

For the marginalised, the church holds the promise of escape from casteism and hopelessness. It’s what drove the Pentecostal movement in Tamil Nadu in the 1980s and what is now playing out in Punjab’s villages among the Mazhabi Sikhs and Valmiki Hindus.

But Caste discrimination does not always end with a change in religion, according to a section of Dalit Christians and Dalit Muslims who have petitioned the Supreme Court for Scheduled Caste status. The Justice Ranganath Misra Commission for Religious and Linguistic Minorities, too, in its 2007 report had suggested that reservation benefits be extended to Dalits who have embraced Christianity or Islam. The Centre opposed these petitions and formed a fresh commission in 2022 headed by former Chief Justice of India KG Balakrishnan.

Lawyer Ashok Kumar, who has been fighting anti-conversion cases in Uttar Pradesh, says that the discrimination among Hindus have led to the rise in Christianity.

“After Kerala and Punjab, Christianity has also reached the rural parts of NCR. In these areas, Hindus belonging to the SC community are discriminated against. The Christians have taken advantage of that. The ones who are not allowed to step in temples are hugged by pastors giving them respect and a sense of identity,” Kumar said.

Back in Ghaziabad, newly converted Pentecostal Christians cite cure more than caste as the real reason behind their conversion. But there is hardly any Hindu from dominant caste groups who is converting.

“You will not find poor people outside a church. If we see anyone, we get them inside and help them achieve a life of dignity through the blessings of Jesus,” said Phillip Swami.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)