Pakistan’s Coke Studio and TV dramas have always been a source of fascination, not just to its own citizens, but also across the border in India. But before all this, there was a thriving industry of Pashto or Pashtun cinema in Pakistan that defined cinema experience for entire generations.

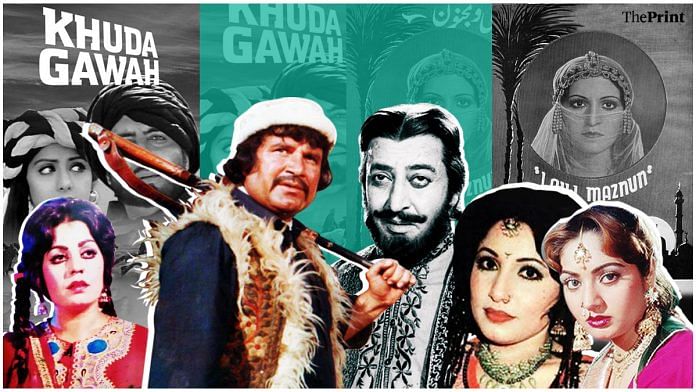

The influence of these movies was so immense that even Bollywood could not resist mimicking Pashto films — just look at the Pathan characters, especially in the movies released in the 1970s. From Pran in Zanjeer (1973) to Amitabh Bachchan in Khuda Gawah (1992) and Feroze Khan in various films — the Pathan was an extremely popular figure. Pashto film industry, too, was drawn to Bollywood, the popular 1975 film Deewar was even remade as Deedan and became an instant big box office success.

However, the Pashto industry, which once had extremely hardcore fans who made weekly movie outings an integral part of their lifestyle, has now faded into a bleak shadow of its former glory.

Also read: The real tamasha in Pakistan — Islamic council that’s saying no to films and corona taglines

The golden era

Laila Majnoon was the very first Pashto-language film made in pre-colonial India in 1939 and the set for the film was built in Kolkata. The film was directed by Rafiq Ghaznavi, grandfather of actor Salma Agha who worked in Bollywood in the 1980s. The film was inspired by a theatrical production of a Pashto-language play of the same name written by ‘Baba-i-Pashto Ghazal’ Ameer Hamza Khan Shinwari.

Meanwhile, the first-ever Pashto film produced in Pakistan was Yousuf Khan Sher Bano that released in theatres on 1 December 1970 and was based on a Pashto folk tale. Amanullah Nassar, a Pashto writer and artist, says, “The film was made with a budget of Rs 2 lakh and managed to earn around Rs 40 lakh.”

The fact that the film was a massive hit among the Pakhtun audience can be gauged by the fact that it completed 50 weeks as the number-one movie after its release. The film’s lead actors, Badr Munir and Yasmeen Khan, also achieved unprecedented fame and adulation, and the Pashto film industry entered its golden era in Pakistan.

Badr Munir, who was a major heartthrob of the Pashto film industry, was a rickshaw-puller in Karachi. It was Pakistani film actor, producer and scriptwriter Waheed Murad who noticed Munir and recommended him for the role, says Nassar.

The industry flourished in Karachi because of the large Pashtun population in the city. The industry focussed on stories of local Pashto folktales and stories of Pathan valour. They also made films on Pathans fighting against the British empire. Even though Pashto movies were technically part of regional cinema, they managed to capture the cinemagoers’ imagination and became very popular. Daud Khattak, a Pakistani journalist based in Prague, says, “As students in Nowshera, we used to go watch Pashto movies in halls, sometimes twice a week.”

Also read: What Imran Khan’s latest domestic headache, Pashtun Tahafuz Movement, is all about

The women of Pashto movies

The women actors in Pashto movies had a certain body aesthetic.

“It was a misconception that Pathans liked curvy or voluptuous women and that is why the actresses were such. In reality, most actresses who retired from the Punjabi film industry due to weight gain turned to Pashto movies,” says Nassar.

The Pashtuns were not keen on their women becoming actors because working in films was considered inappropriate for women. So the industry, interestingly, never had a Pashto-speaking actress. Instead, it was full of Punjabi or Urdu-speaking women, and their lines would be dubbed. Pashto cinema did harbour well-known talent like Nadara Mumtaz, Suriya Khan and Musarat Shaheeh. Shaheen later became a politician and formed her own party, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Masawat (PTM).

According to a 2013 report in Pakistani daily Dawn, a family in the largely ethnic Pashtun northwestern province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa even killed their daughter for pursuing singing in movies. Despite that, women did sing. Liaqat Taban, who is a fan of old Pashto films, says that Pashto music was very popular. Gulkara was an important Pashto singer and contributed to the fame of the music in various parts of the world. Pashto music cassettes were popular once as well.

But when the decline of the Pashto movie industry started, even established actors like Suriya Khan were left without means of livelihood. The actor began her career when she was still in school. Khan had been part of 140 Pashto movies and won several awards, and even produced three famous movies. But with the decline of the industry, she had to ask her fans to help her with her financial crisis in 2020.

Also read: I compared Afghanistan school textbooks with Pakistan’s. This is what I found

Decline, bombing and 9/11

The turn in the tide came when the Pashto film industry shifted to Lahore from Karachi in the 1980s. Zia-ul Haq coming to power meant a variety of restrictions on everything, especially on art and culture. Lahore became the centre, and everyone moved to the city to avail better opportunities. But not everyone could afford to stay on and work in films for days on end in an expensive city like Lahore. The Pashto music cassette industry too shifted to Peshawar and other parts of Pakistan.

Haji Mohammad Aslam Khan in his book Pakhto Filmoona, writes that in the 1990s non-Pakhtun filmmakers began to proliferate the industry. Nassar says, “When businessmen took over film production, the quality became terrible.” Actors, writers, and investors began to drift away, while many quit the profession entirely.

Nassar further adds that the 9/11 attacks played a major role in the decline of Pashto cinema. In neighbouring Afghanistan, Taliban banned cinema and music for being ‘un-Islamic’ in the early 2000s. Several cinemas were also attacked and even bombed in Pakistan. Compounded by a decline in content that began to focus on a lot of kissing, dancing and violence, the industry slowly began crumbling.

“I saw a film once that had 15 dances. It is the CD/internet generation that took over, and filmmakers stopped making good films,” said Nassar.

The advent of internet streaming struck the death blow to Pashto cinema and the culture of watching movies in single-screen halls. Halls soon gave way to malls and shopping complexes even in smaller towns, says Khattak.

Cinemagoers declined, halls shut down and art turned to commerce. ‘Vulgar’ songs and dances replaced the stories that once even used to depict social evils prevailing in typical Pashto society. Cinema halls have dwindled from 25 to 1 in some places in Pakistan, while others had no halls showing Pashto films altogether. Now, the films are made fun of or mocked at for the kind of content they had.

The legacy of Pashto films has been reduced to shady movie halls that reek of cigarette and decay. There are still fans among the poor working class who watch these films.

Nassar, however, finds hope in some shows in the Pakistan TV industry. Parizaad, a show whose final episode was also screened in halls, is the example he gives, of thought-provoking content like old Pashto films. But the old world of family entertainment, moral lessons, romance, comedy and even villains with brand names similar to India’s Amrish Puri is probably lost forever.

(Edited by Rachel John)