New Delhi: They go by many names, including “readymade wives” and “modern-day Draupadis”. They are shared among brothers to save wedding expenses, and to keep family land from fragmentation.

Now a book insists they are happier than their monogamous counterparts.

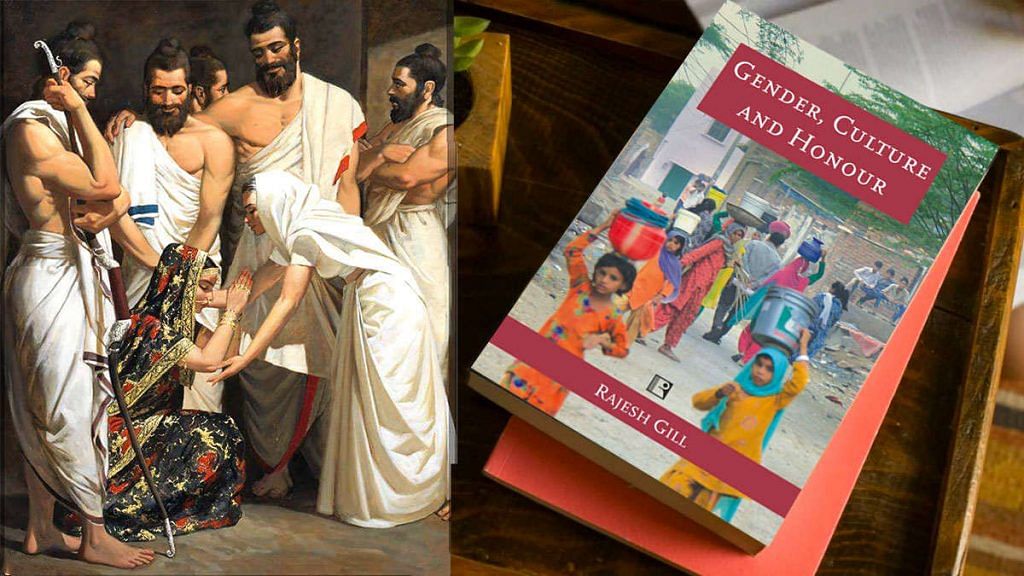

Gender, Culture and Honour by professor Rajesh Gill (Rawat Publications) seeks to analyse the daily life of women from various perspectives like caste, patriarchy, religion, age and culture etc.

However, it has become a subject of fervent discussion among social media users from Haryana and Punjab on account of its observations on an ancient practice of polyandry — ‘Draupadi pratha’, still followed in parts of the states — where a woman is shared as a partner among brothers

According to the book, women in such arrangements were found to be “extremely cheerful, satisfied and happy, unlike their counterparts in other households”.

The book, Gill said, involved four years of field research.

“When my research team told me that women are happier in such marriages, I asked them to revisit and check their findings once again,” she added in an interview with ThePrint. “Finally, we found in our research that these women have never been victims of domestic violence.”

The system draws its name from the mythological figure of Draupadi from Mahabharata.

The Pandavas, the five brothers who are among the protagonists of the epic, shared Draupadi as a partner because their mother Kunti is believed to have told them to share everything.

Gill said ‘Draupadi pratha’ was “not a new family arrangement and has been followed for several generations”.

“We cannot form a ‘right or wrong’ opinion about it. Our job is to reveal the social changes being ushered in by changing economic systems,” she added.

Gill said they came across the practice in the districts of Fatehgarh Sahib and Mansa in Punjab and Yamunanagar in Haryana among Gujjar Muslims.

Weak financial standing of families was the primary motivation to go for the practice, since it helps avoid divisions of property and the pressures of organising multiple weddings, she added.

Also read: In the call for Ram’s Mandir, the birth of Sita continues to be a mystery

‘Keeping all happy’

The book quotes “male respondents in village Daulatpur” as saying that it is a “normal practice for all the brothers not to marry”.

“Instead, one of them would marry so that there is one woman to take care of the kitchen and other domestic chores. She would serve all the brothers, since all of them have a share in land,” the book adds.

“These women keep all of them happy…all the brothers treat the children as their own,” the book quotes a 50-year-old panchayat member as saying about the practitioners of ‘Draupadi pratha’.

A 32-year-old from Panechan village, according to the book, summed it thus, “These men (unmarried) work in the fields, have small land and in return they get served.”

“When you get a readymade wife at home, why get married?” an unmarried man from Fatehgarh is quoted as saying.

Women quoted in the book also speak fondly of the practice. “The sister-in-law (bhabhi) enjoys earnings of all the brothers,” one says.

Others describe the “privileges” enjoyed by the brother who gets married. “The brother who is married… is called ‘lanedaar’… He enjoys the highest status among the brothers and in the household,” the book says.

“When one brother goes inside, he leaves his shoes outside… so that the other knows that he is inside,” a 50-year-old is quoted as saying.

Gill said the “tradition” was also followed in several other states “under different names and identities”.

“There are two major types of polyandry — one is called fraternal polyandry where all the husbands of a woman are brothers… and the second one is called non-fraternal polyandry where husbands sharing a wife are not necessarily brothers,” she added.

In 1999, India Today had done a report on a similar practice followed in western Uttar Pradesh, for similar reasons.

A vital question here is how any woman is convinced to establish a constant physical relationship with more than one man. Gill said women didn’t have a choice at the outset.

“The family elders and/or in-laws play an important role in it,” she added. “They try to convince the women by citing ‘anguthe ka mamla’ (property), the importance of saving money that might be spent on marriages and a need to keep the ancestral property intact.”

Speaking to ThePrint, a woman sarpanch from Haryana backed this claim.

“Women are not informed about this before marriage,” she said. “It is something they learn after marriage. They adjust with time.”

Two progressive states

‘Draupadi pratha’ can also be placed in the context of Haryana and Punjab’s poor sex ratios — according to government thinktank Niti Aayog, Haryana had a sex ratio of 831 (it has 831 women for every 1,000 men) in 2013-15, while Punjab’s stood at 889.

Both have registered minor improvements over the past few years, but there remains a wide gap between the male and female populations, a scar from the flagrant female foeticide once practised in the states.

As a result, there has been a growth in the number of bachelors and several local songs seek to depict their misery.

During the recent Haryana assembly elections, some youths from Jind also formed a ‘Bachelor’s Union’, which was seen raising slogans such as “votes for brides (bahu do, vote lo)”.

Several politicians promised that, if elected, local youths will face no difficulty getting brides from outside the state.

Asked if the tradition of ‘Draupadi pratha’ will die or flourish with weaker economy and growing unemployment, Gill said it could not be predicted yet.

“With the growing number of bachelor boys and weaker status of economy, it is hard to say if this tradition is about to end soon,” she added.

Also read: Millions of women absent from India’s workforce capable of adding Rs 30 lakh crore to GDP