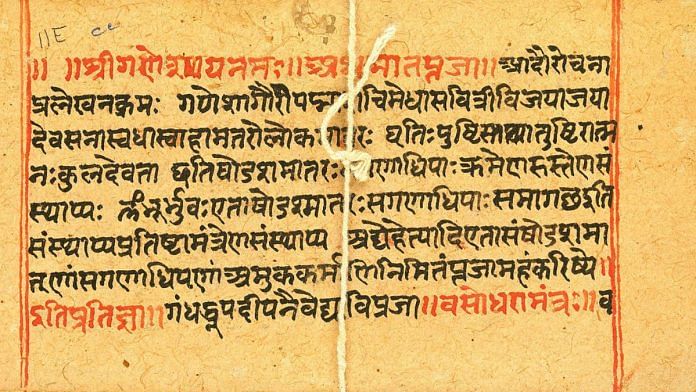

From Beijing to Jakarta, Kathmandu to Tokyo, former foreign secretary Shyam Saran has served across countries. Often, he discovered collections of Sanskrit texts carefully preserved in these nations but lost in their land of origin.

“These are bountiful sources of cultural and historical knowledge,” he told ThePrint. “I brought this up with Sudha [Gopalakrishnan], who’d been working to preserve our manuscripts, and SAMHiTA [South Asian Manuscript Histories and Textual Archive] began to take root,’’ said Saran—who is also president of the India International Centre—while speaking to ThePrint.

A recent webinar, Kriti-SAMHiTA: The Plurality of Indian Knowledge Systems, organised by IIC on Saturday, brought together experts engaged in the conservation of traditional knowledge—from the Malayalam language to old South Asian manuscripts. The event saw Shiju Alex and Heike Oberlin—two heritage scholars dedicated to conserving India’s cultural and historical wealth—share the experiences and challenges that come up while researching, sourcing and digitising such records.

The origins of SAMHiTA

In the Vedas, Samhita refers to a collection of sacred hymns, and this modern version is no less.

SAMHiTA is being developed by IIC’s International Research Division and intends to make the dialogue of ancient India more accessible to the world by collaborating with international organisations to create a digital compendium of South Asian manuscripts.

“This database aims to make available Indic manuscripts and knowledge in architecture, spirituality, scripture and more to scholars across the world for critical research. SAMHiTA is open access to allow anyone with an interest to make use of it,” Gopalakrishnan, who hosted the webinar and also spearheads the SAMHiTA mission, told ThePrint.

Explaining the efforts being made toward conservation of traditional language and culture, Gopalakrishnan said that “The internationalisation of this national focus on manuscripts was the natural next step,” she said.

The pilot for SAMHiTA was launched in March 2022—with support from the Ministry of External Affairs—and the project is slated to run till July 2023. The aim is to focus on identifying, estimating and preserving manuscripts of India’s heritage that have found homes across the world. Where there are digital versions available, they aim to integrate them into this collection. Where there are none, they look to utilise their resources for digitisation. The collections of SAMHiTA largely include Sanskrit texts and translations but are rapidly expanding to make space for more manuscripts from other languages in the Devanagari and Dravidian scripts.

“This study of manuscripts has become a way for Indians to reclaim their intellectual heritage from colonial domination, dispelling false beliefs,” Gopalakrishnan said. “This is a duty that extends beyond any one institution, and is a global responsibility. It is a responsibility of India to the world,” she added.

Also read:

Granthapura and Gundert

SAMHiTA also aims to bring together scholars for cultural and academic exchange regarding these efforts, said Saran.

At the IIC webinar with this cause, we are introduced to Alex and Oberlin.

While Oberlin is Head of the Indology department at Tubingen University, Alex is a Senior Technical Writer with ABB Robotics in Bengaluru.

Alex has put his heart into preserving such windows into India’s past. He volunteered his free time to do digital archiving activities. In his presentation at the webinar, he detailed his 12-year-long experience archiving manuscripts.

“It started out as a hobby on my website. My involvement in the Malayalam Wikipedia community drove me to find sources,” he said. These sources stretch back to the first Malayalam texts. The first Malayalam printed book, Sampkshepa Vedartham, a collection of religious teachings by Italian priest Clement Peanices and the Malayalam Ramban Bible were among the first of entries on his website.

The digital archiving project started to get appreciation from scholars and the media. “But soon, I had run out of available books. They were unavailable to me, stored in government or private libraries,” he added. However, Alex was determined. Researching, he learnt about a special collection of manuscripts at Tubingen University in Germany, belonging to a 19th– century German linguist, Hermann Gundert, who fell in love with the Malayalam language while on a trip to Madras.

Shiju reached out to Heike Oberlin, Head of the Indology department at Tubingen to digitise Gundert’s library. With support from the German Research Foundation, they took on this challenge. Over 24,000 pages were scanned for open access on the ‘Gundert Portal’ launched in 2018. From a Malayalam-English dictionary crucial to study the development of the language to notebook and palm leaf manuscripts describing Ayurvedic treatments, they brought it all online.

With Malayali volunteers located all over the world, they transcribed many of these pages into Unicode—an international encoding standard for different languages and scripts. Unicode has been used by Google to train Artificial Intelligence (AI) in optical character recognition: An essential tool to analyse Malayalam documents on the internet today.

Shiju has now founded the Indic Digital Archive Foundation to continue these efforts with languages across the country. Their expanding collections are available through Granthapura, an aggregation of public domain manuscripts in Kerala maintained by Shiju’s nascent foundation. The Gundert portal is available through the Tubingen University website.

“Gundert’s fascination lent itself to an openness that meant he talked to people across the social hierarchy. His dictionary contains layers of language as they were used in different aspects of the polity. This openness is something we can aspire to in our world today,” Oberlin said.

The mission is of great magnitude. “The International Research division at the India International Centre estimates that there are about 200,000 Indic manuscripts spread across 200 centres,” said Gopalakrishnan.

She said that well-wishers and academics must step up to make this project a success. “Institutions with manuscript holdings can share digital capacities. Manuscript libraries can aid in sharing catalogues and digital scans.” However, there is a role for many in this process. “Open source technologies can be aided with, and funding agencies will need to provide financial support,” added Gopalakrishnan.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)