Guwahati-based photographer Ankha Millo asked an artists’ collective in the Northeast why they don’t have more women members. The answer was a shocker.

“It’s because women seem to be so wrapped up in domestic issues,” the 32-year-old Ankha was told.

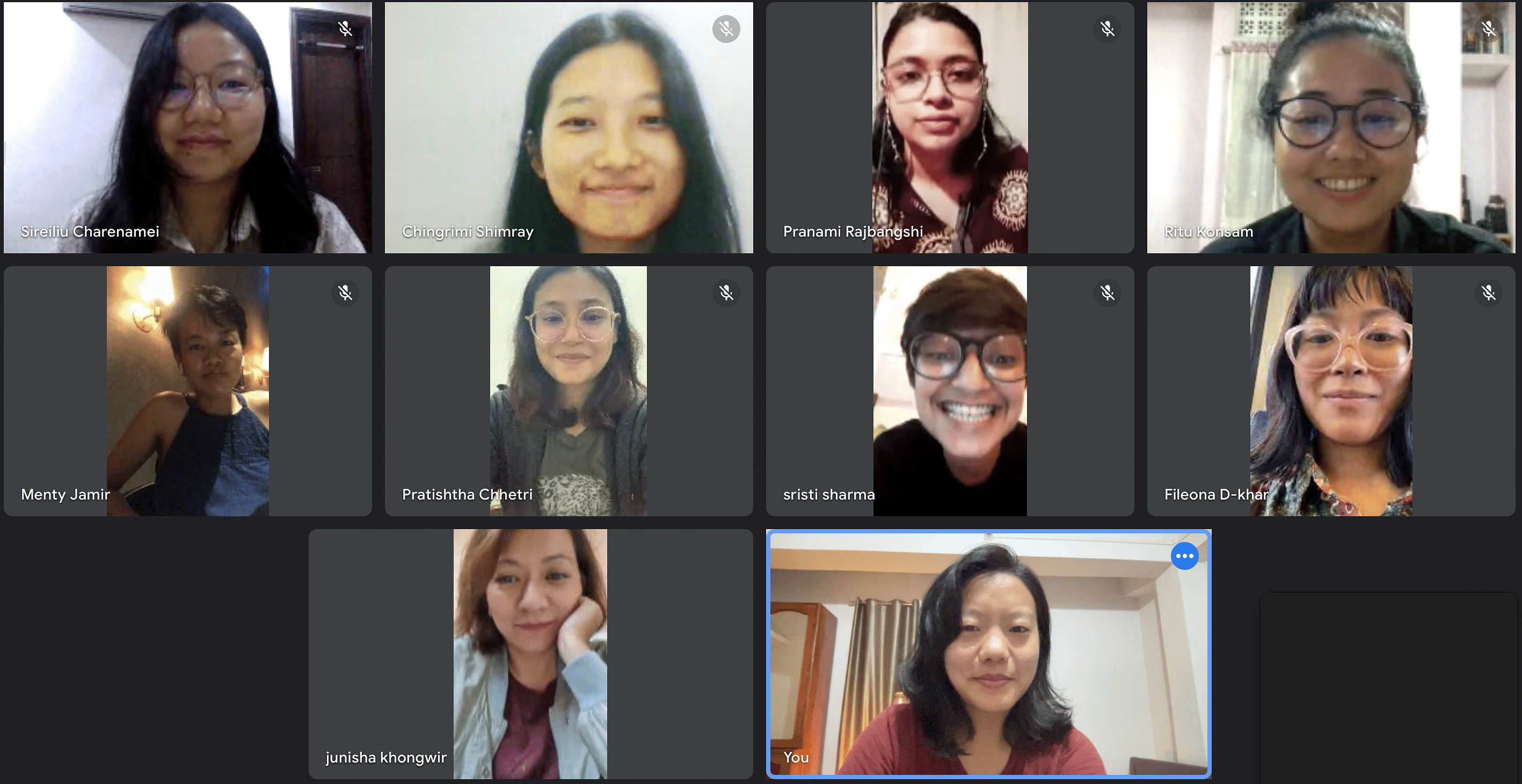

That was 2021. Today, she and nine other women photographers from Meghalaya, Sikkim, Assam, Manipur, Nagaland, West Bengal (Kalimpong), and Arunachal Pradesh run their own collective called Aama, which means ‘mother’ or ‘grandmother’. In April this year, they decided to take their work online and set up their Instagram account @aama.collective.

These women see themselves as a new band of visual storytellers of a region that the rest of India often stereotypes. With their work, they want to alter the perception about women photographers from the Northeast, while prioritising their safety when out in the field.

“There’s more to us than our domestic lives; that’s just one aspect,” says Ankha.

The Aama Collective is their safe space where they share stories. “We exchange field notes from different parts of the region.”

About 30 women photographers for every 100 male photographers in the Northeast – this is what the Aama Collective hopes to change.

Also read: A Kumaoni Dalit is singing Qawwali in Delhi, won’t let folk music trap him in his caste now

Representation of diverse cultures

A Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) student from Manipur, a documentary filmmaker from Kalimpong, a visual artist from Meghalaya based in the Netherlands—Aama’s diverse group is bound by a common thread: its members use photography to show the different facets of their culture.

Junisha Khongwir, an assistant professor of mass media at St. Anthony’s College in Shillong, often trains her lens on the culture and life of the Khasis in Meghalaya. One of her photographs, ‘Monsoon in Laitlyngkot,’ frames a man clad in a shawl holding an umbrella as he walks past a worn-down building. Pops of colour in the green moss thriving along the boundary walls of the building add to the stark beauty of the predominantly black and white photograph. This is monsoon in the small East Khasi town.

Ankha’s muse is the Apatani tribal women in Ziro town of her native state Arunachal Pradesh. She shifts from a woman working in solitude in the hills to a trio preparing a meal in “an attempt to understand feminism in a tribal landscape”.

For 26-year-old Anna Sireiliu, who belongs to the Liangmai Naga tribe of Manipur, the camera is a window to Thonglang Akutpa village in the Kangpokpi district where she grew up. “We shifted to Delhi where my father was posted when I was eight years old…[but] I was very close to my native village,” says Anna, who is currently doing MPhil in visual arts from JNU.

Anna’s images capture the generosity of villagers when resources are scarce. “My village is poor, yet they are so generous with their food…our feasts become diplomatic sites where people of different communities – Nagas, Kukis, and Nepalis – converge. One of my projects is to explore that. My village really inspires me to pick up the camera,” she says.

All these projects have started taking shape only recently. Five years ago, when Ankha decided to become a photographer, the landscape was mostly male-dominated. “In 2017-2018, I was invited to Manipur for the Sangai Photo Festival…I was the only woman who showed up. That’s when I started looking for women photographers from the region,” she says.

Also read: Attention influencers. You may soon be fined lakhs for false ads, or not disclosing paid content

When women come together

The idea for the Aama Collective came from a photography workshop by Northeast Lightbox, a collective of artists, in 2019 on the riverine island of Majuli in Assam. Apart from Ankha, there were only two other women in the workshop, one of whom was a mentor from New Zealand and the other was an anthropologist from Assam.

One of the mentors at the workshop, Guwahati-based photographer Prakash Bhuyan, broached the idea of a women’s collective. “Prakash cited two examples from Myanmar—the Thuma Collective and the Kaali Collective. The seed for our collective was planted there,” says Ankha.

A year later, India was in the throes of the Covid pandemic. But Ankha and her group braced the turbulence and formed the Aama Collective in July 2020.

At the time Ankha had already been following the works of other photographers in the Northeast as she was “looking for a sense of community.” She reached out to several of them, mainly over Instagram, and floated the idea of the collective. The response she got was overwhelmingly positive.

“Seven-eight of us got on a call. I had mostly sought out those who were from the region. Photography can be a lonely practice. I just felt that this was a good chance for us,” Ankha says.

Most of the women were functioning out of silos with little support from other photographers. Netherlands-based visual artist and researcher Fileona Dkhar says she was back home in Meghalaya during the pandemic when Ankha approached her. “I was doing street photography [at the time], I was alone and didn’t have anybody who could look at the images. Aama offered a network of peers who would look at my work and give feedback,” she says.

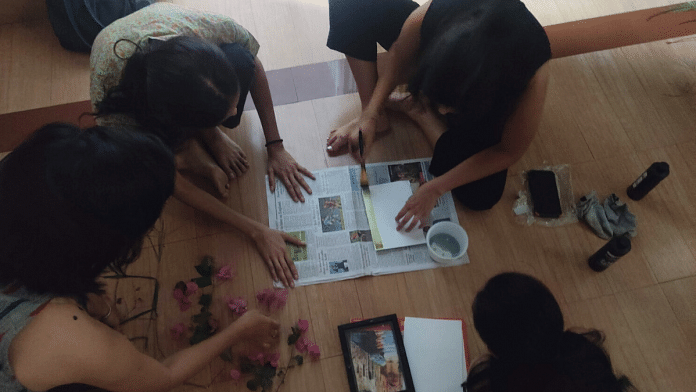

The women have met just once in person, in Guwahati in March 2021, but they hold virtual meetings on Zoom or Google Meet at least once a month. It took several rounds of online meetings for the group to get to know each other. An essential part of the process was a “pilot project,” which required the photographers to document anything they wished for three to four months before presenting it to each other.

“This really broke the ice, we got to see the space each one of us came from and when they were sharing the stories they were very vulnerable,” says Ankha. Many would cry as they spoke of their loneliness, fears and even their relationships.

The meetings where bonds are reaffirmed and strengthened often last for more than a couple of hours. “I’ve spoken about how isolated I felt when I moved away from my hometown (Dehradun and Kalimpong),” says Pratishtha Chhetri, a Pune-based documentary filmmaker and a professor at Symbiosis School of Visual Arts and Photography. “Those meetings are wonderful, it’s a very cathartic space.”

Also read: What is the olive oil controversy? Don’t worry, it’s perfectly suited to Indian cooking

A safe and significant space

For the 10 photographers, the Aama Collective has facilitated their work while reaffirming their cultural identities. Pratishtha, whose family is from Kalimpong in Darjeeling, was constantly on the move as her father was in the Army.

“So, whenever I would go back home, I was not Gorkha enough, and then in Delhi, I wasn’t north-eastern enough,” Pratishtha says. Though she no longer lives in Darjeeling, the Aama Collective is a way for her to reclaim her roots and identity.

Members of the collective say that the conversations also revolve around the realities they face as women working in the field. A lot of thought goes into dressing in a particular way for a field trip to avoid giving the wrong impression. “It’s different for a man,” says Ankha.

Sexism in this field runs deep, but unlike other professions, it’s not really talked about openly. Pratishtha recalls her experience working at a production house as a creative director. The camerapersons didn’t like taking orders from her, she says. Getting travel assignments was not easy and acceptance among male colleagues was a daily challenge.

By sharing their experiences and coming up with solutions, the women are slowly coming to realise that they are not alone. Members feel that as a collective, their voice is louder and more powerful.

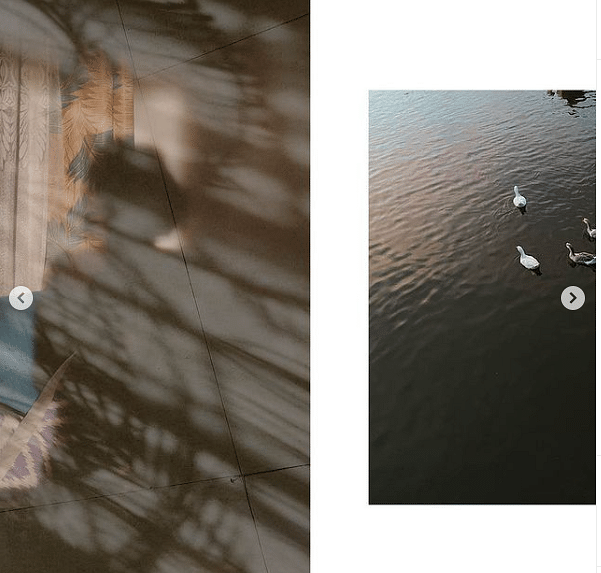

In August 2022, Aama started a weekly “visual newsletter”– an Instagram post with carefully curated photographs and at times, prose and poetry as well.

‘Do not rush me. I am afraid, there is so little I know of myself’ read the snippet by Anna against a negative image of a bird in mid-flight clicked by Ritu Konsam, another member of the collective.

Some of the photographs are a play on colours and shadows. One picture by Ankha and Ritu has a silhouette of a woman inside a room superimposed over another image of the shadows of leaves.

“The Instagram page has grabbed a lot of attention from established artists and photojournalists,” Anna says. Many of the members have started working on collaborative projects with other photographers and organisations. Pratishtha and another filmmaker are producing a documentary on Gorkhaland. Pratishta, who teaches at Symbiosis, helped photographer Menty Jamir organise a workshop for students. The women help each other frame proposals for projects and grants.

He’s not a member, but Prakash Bhuyan from Guwahati is ecstatic about the potential of the Aama Collective. “It will work towards destabilising power structures. It can also become a part of a network of such collectives in South Asia and Southeast Asia,” he says.

The Aama Collective’s next milestone will be an exhibition. They have sent proposals to participate in two festivals in the Netherlands and in Tripura. “Things are looking up,” Ankha says.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)