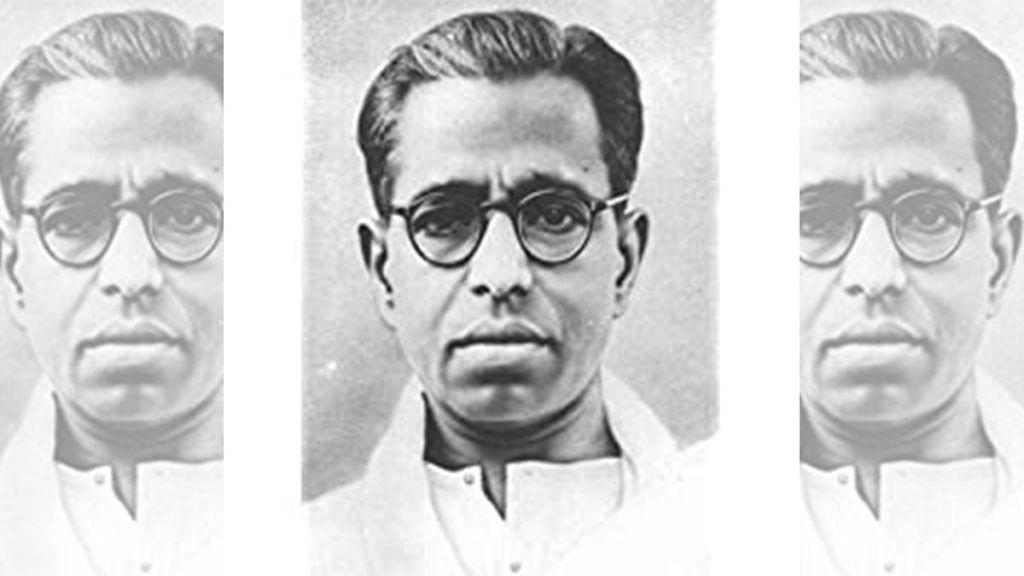

New Delhi: R. Krishnamurthy, better known by his pen name Kalki, is credited with ushering in a literary era in South India that raised the standard of the Tamil novel.

However, Kalki donned many hats in his lifetime. Aside from being an author, he was a journalist, activist, poet, music critic and playwright in the 1930s and 40s.

The Sahitya Akademi awardee penned 120 short stories, 10 novellas, five novels, three historical romances and other musings. But most prominent were his works in historical fiction, particularly Ponniyan Selvan, a 2,400-word cult novel that glorified the Chola dynasty — a Tamil empire that is believed to be one of the longest-ruling dynasties in the world history.

The novel is currently being adapted into a film directed by Mani Ratnam, starring Amitabh Bachchan and Aishwarya Rai.

While Ponniyan Selvan established Kalki as a formidable literary figure, he did not see himself that way.

His granddaughter, Gowri Ramnarayan, a playwright, theatre director and former journalist, tells ThePrint, “He didn’t see himself as a literary figure but as a prachara ezhutthaalar (propagandist) of Gandhian views.”

Kalki did have a long association with Gandhi and the freedom movement. According to Ramnarayan, he dropped out of school to join the Non-Cooperation Movement in January 1921.

He faced imprisonment at least thrice and later joined the Congress party to produce propagandist literature. Kalki also translated Mahatma Gandhi’s autobiography ‘My Experiments with Truth’ into Tamil.

Interestingly, Ramnarayan, currently working on a translation of her grandfather’s magnum opus Alai Osai, which tells the story of India’s journey to independence through the eyes of the common man, notes that not a single character from the Congress party features in the book though the “spirit of Gandhi remains throughout”.

Apart from chronicling the rise of the Chola rulers in Ponniyan Selvan and India’s freedom movement in Alai Osai, Kalki wrote about Pallava dynasty in Sivagamiyin Sapatham, women’s emancipation in Thyagabhoomi, tragic romance in Kalvanin Kadhali and often used humour in his writing.

Kalki died of tuberculosis on 5 December 1954 at the age of 55 years. On his 66th death anniversary, The Print remembers the life and times of the great writer.

Also read: ‘Elephant Boy’ Sabu Dastagir, the first Indian actor to make it big in Hollywood

From college drop-out to master of literature

Kalki was born on 9 September 1899 in Puttamangaiam village, Tamil Nadu, to a “poor Brahmin family” and lost his father at the age of 6 or 7 years.

As a boy, he quickly became a fan of Subramania Bharati’s poetry and upon his death, played a key role in collecting funds and building a memorial for the legendary Tamil poet at his birth place in Ettayapuram in 1945.

Kalki attended three schools — one in his village, one in the adjacent village and the National College, Tiruchirappalli, from which he eventually dropped out to join the Non-Cooperation Movement. When he left, the then principal of the National College wrote to his elder brother asking him to convince the “shining star” to return, granddaughter Ramnarayan tells ThePrint.

In 1924, Kalki married his wife Rukmini, who was eleven years his junior — he was 25 and she was 14. They had two children.

Kalki first thought about entering journalism while working for Navsakti magazine — a Tamil journal established by scholar V. Kalyanasundara Mudaliar. He was later mentored by C. Rajagopalachari or ‘Rajaji’, the last Governor-General of India, at the Gandhi Ashram in Tiruchengode.

After contributing to Tamil weekly Ananda Vikatan, Kalki was made the editor of the magazine before launching his eponymous magazine in 1941. At one point, Kalki’s magazine, hit a weekly circulation of 71,366 copies in newly independent India.

Kalki’s works were often in the form of serials or sequential instalments, which were then converted into books. He also went by Tumbi, Tamil Teni, Ra Ki and 10 other pseudonyms at different points of his life.

He was also a music critic and along with legendary vocalist M.S. Subbulakshmi and others, helped propel the Tamil Isai movement — which sought to promote Tamil music at a time when traditional Carnatic musical compositions were restricted to languages like Telugu and Sanskrit.

Also read: J.C. Bose — ‘Father of Radio Science’ who was forgotten by West due to his aversion to patents

Why ‘Kalki’

There is a common misconception that the name ‘Kalki’ was derived from the prefixes of his and his wife’s name in Tamil.

However, he once revealed in an interview, that he chose the name Kalki after the tenth and last avatar of Lord Vishnu because he felt it fit for someone bent on destroying regressive regimes and expressing radical thoughts at the time, whether it was women’s emancipation or freedom from bondage.

Kalki was a rebel even with his own writing. As Ramnarayan explains in her introduction to a compilation of translated stories titled Kalki Selected Stories: “Kalki’s short stories defy all the norms and rules of the genre; some of them are too long to be called short stories, some are really abridged novels masquerading as short stories, [and] many of these tales have little plot and less structure…”

On Kalki’s birth centenary in 1999, the Government of India released a postage stamp in honour of the “first writer of Tamil prose to take it to the masses”.

Also read: ‘Murari Lal is anxious’ — Gulzar says common man worried by lost leadership in latest poem