Meerut: When the pandemic took away his sales job in 2020, Sachin, a resident of Meerut in Uttar Pradesh, did not despair. Instead, he started to dream.

A Dalit, he had for long watched his father, a municipal worker, clean other people’s dirt. But what if the family turned caste expectations on their head and made a fortune by manufacturing toilet cleaning solutions, he thought.

“I thought of setting up a small factory with two machines to make toilet cleaners. My younger brother [who is a chemistry graduate] had the knowledge and I had the skills of marketing and other things,” Sachin, who is now 32 and has a Bachelor’s degree in computer applications, said.

Revved up, Sachin and his younger brother Vipul put in an application for a Rs 7 lakh loan under the Prime Minister Employment Generation Programme (PMEGP), which is geared towards giving a leg up to small entrepreneurs.

However, the dream has slipped farther away with each passing year.

“Our files have been rejected twice. This is the third time we will apply,” Sachin told ThePrint in the last week of April, requesting that his full name not be used in case it affected his loan prospects.

When ThePrint spoke with district officials at the Industry Department, they said that Sachin and Vipul had the education and skills required to be eligible for the entrepreneurship loan, but the bank had turned down their request because the brothers did not have social security assets such as land or a house.

“The State Bank branch in the city where my brother’s account was registered said we should avail of the loan from some other nearby bank,” Sachin claimed.

It’s a situation riddled with irony: the Centre as well as the Uttar Pradesh government are encouraging young people to start small businesses in tier-2 and -3 towns — through multiple subsidised loan schemes like One District One Product (ODOP), Mudra Loans, and PMEGP — but there are either problems with bank requirements, or obstacles in accessing market due to factors like a lack of understanding of marketing and demand generation.

ThePrint travelled to Meerut, an important industrial hub in UP, to see how initiatives to encourage ‘startup culture’ and self-employment outside of the metros are panning out.

Also read: Unemployment and unlimited data pack — UP’s youth are neither angry nor idle

‘Not really a startup culture’

Last month, the Union Ministry of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSME) released a statement that said an “unprecedented” 1.03 lakh new manufacturing and service units and more than eight lakh jobs had been created under the PMEGP.

The Commerce Ministry, too, has released figures showing that startups have increased from just over 700 in 2016-17 to more than 66,000 as of March this year. What’s more, about half of these are from tier-2 and -3 cities.

Every now and then, there are glowing communiques about the schemes Uttar Pradesh is supporting, like ODOP, which aims to encourage the state’s unique handicrafts and products, and the Mukhyamantri Yuva Swarojgar Yojana (MYSY), which seeks to provide self-employment opportunities to educated, unemployed youth.

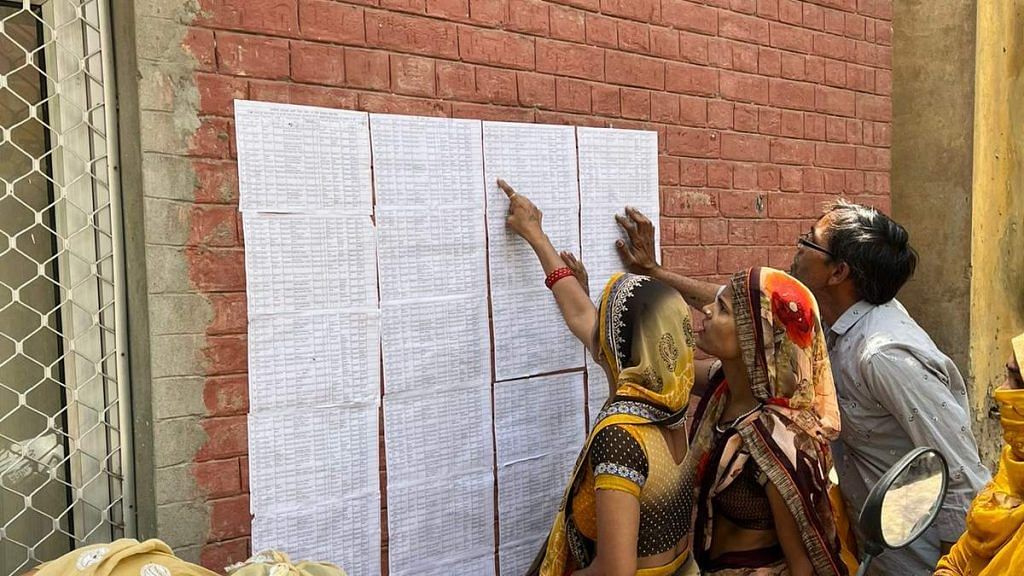

ThePrint accessed data on these schemes from the Meerut district administration and found what seem modest upward trends in loans for self-employment.

For instance, the beneficiaries of the MYSY self-employment scheme rose from 77 in 2019-20 to 97 in 2021-22. The grant amount also increased to Rs 3.1 crore in 2021-22 from Rs 1.99 crore in 2019-20.

“We have achieved the assigned targets of our district over the years,” V.K. Kaushal, general manager of the District Industries Centre (DIC), which is tasked with promoting MSMEs at the district level, said. “The numbers reflect in other schemes too,” he added.

Indeed, ODOP beneficiaries in Meerut have increased to 45 in 2021-22 from 17 in 2019-2020, and to 43 from 13 in the same period under the PMEGP. The subsidised loan amount given in 2021-22 stood at Rs 1.36 crore, up from Rs 32.02 lakh in 2019-20.

However, MSME loan distributions in Meerut paint a slightly different picture. While there were 45,116 beneficiaries in 2019, there were only 24,385 in 2022. The loan amount declined from Rs 4,291.82 crore in 2019 to Rs 3,601.17 crore in 2022.

Speaking to ThePrint on condition of anonymity, an assistant manager-rank official at the DIC said that while beneficiaries of various schemes were increasing, this did not necessarily mean that innovative new ventures were getting off the ground.

“What is happening right now is not really startup culture. Those availing of loans below Rs five lakh rupees cannot really build a business. The funds end up being diverted for personal reasons,” the official said.

The demographics of beneficiaries of institutional loans also suggest that “youth”— people in their 20s, fresh out of school or college — are not exactly flocking to start their own ventures.

Most beneficiaries, in fact, are in their 30s or even 40s, and some already have prior experience in running their own businesses. “In 2017, we had difficulties explaining why people need to avail these loans. But things are slightly different now. To gain the trust of those in their late 20s, we have a long way to go,” the DIC official said.

Also Read: How GST is killing small businesses with inspector raj and suffocating compliance

Low demand, funds diverted for personal use

Harsh Bhatnagar, 32, looked harried as he arrived on his scooter at his noodle factory, which he runs from a 300sq-ft premises on the outskirts of Meerut city. Business has not been doing well and it is a challenge to pay his seven employees.

“I had to sell my car. My house papers are also with a person who lent me Rs 3 lakh,” Bhatnagar said, adding that he was close to shutting the unit in the wake of Covid lockdowns, which left him in debt, unable to repay the Rs six lakh MUDRA (Micro-Units Development and Refinance Agency) Loan he took to set up the business in 2015.

Bhatnagar, who has a Bachelor’s degree in commerce, said that since the Covid lockdowns, a significant chunk of his market — street vendors and small eateries — have closed operations. “All my clients are gone,” he said.

He is hoping that another loan might help him stay afloat, but has been struggling to get one. “I plan to again apply for another loan under PMEGP,” he said. District officials have assured him that they will help him persuade the bank, he added.

While Bhatnagar has been engaged in the noodle business for several years, newcomers like 32-year-old Ashu are also finding themselves in a precarious position.

In 2021, Ashu, a research scholar at Chaudhary Charan Singh University, applied for a Rs 1 lakh loan under UP’s self-employment scheme to set up a vermicomposting plant. “I wanted to build an authentic business,” he said. Like many other small-town entrepreneurs, he drew inspiration from his family’s background, in this case farming.

At first, the process was smooth and he did not have to struggle to convince the bank to give him a loan since his family owns a modest four acres of land in Muzaffarnagar. However, while there may be a need for compost in Meerut, Ashu was floored when he was confronted with the fact that demand was already outmatched by supply.

“There is cheap compost available on Amazon, and there is a lot of local competition too. There are 10 to 15 companies in Meerut alone selling compost for home gardening,” he said.

Currently, Ashu’s ‘Paudha Amrit’ (plant elixir) compost doesn’t have many takers, leaving him worried about his future.

“I don’t want to go into teaching. I have high hopes that if this works out, I will give a boost to this startup,” he said. He hopes to be able to work on marketing and to arrive at competitive pricing if he manages to stay above water long enough.

District officials acknowledged that problems of the kind Harsh and Ashu are facing are not uncommon and new businesses are finding it hard to flourish for a number of reasons.

“We need skilled and knowledgeable youngsters to join the industry and start new avenues, but two lockdowns have badly affected the spirit,” the DIC official quoted earlier said.

To address the issues of “knowledge and skill”, the Yogi Adityanath government announced last month that it will launch an online course and certification on entrepreneurship. The spin, of course, is that young people should become job-creators rather than job-seekers.

However, major systemic obstacles are apparent.

One is that the loan schemes are driven by supply-side factors, such as set targets for each district, rather than demand.

In the market, too, demand is is often a problem, which means that sustainability of businesses is an issue, especially in the absence of marketing know-how. There is also little focus on viability assessment — at times, for instance, entrepreneurs get raw materials from distant areas, which negatively impacts their profit margins.

Other ancillary aspects of a startup ecosystem are also in short supply, such as mentorship programmes, technical assistance, incubation centres, and collaboration schemes between the government, educational institutions, and private enterprises.

According to district magistrate Deepak Meena, there is another factor at play: Meerut already has manufacturing industries, especially in the sports equipment sector, and so there are more employment opportunities in these established industries and thus less of a push for young people to start new enterprises.

Add to this scenario the lasting impact of Covid lockdowns, and the entrepreneurship landscape in Meerut currently does not seem to include a startup boom anywhere on the horizon.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)