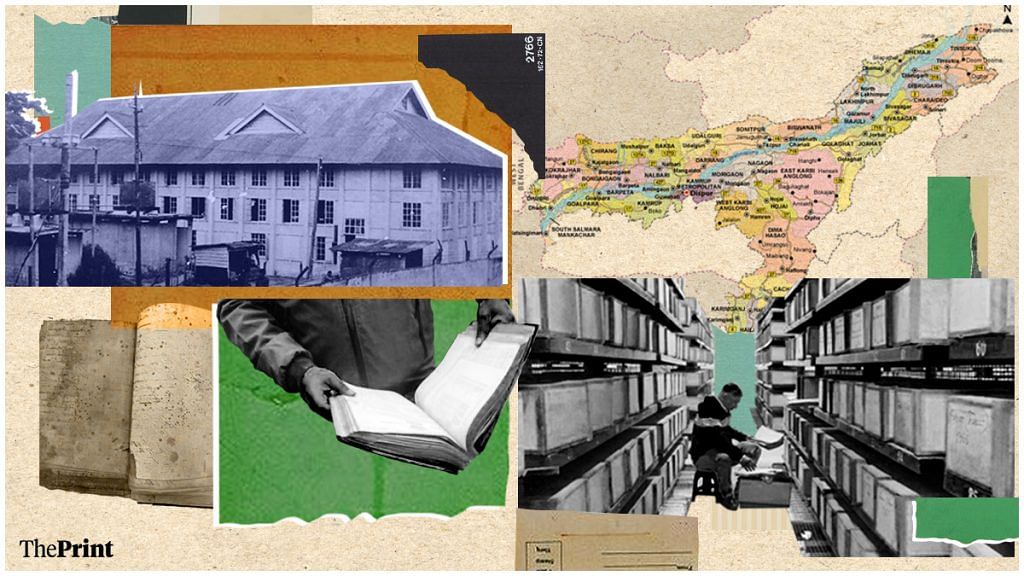

In India, archives are where public records go to die a dusty, decayed, derelict death. But in an almost universal story of neglect and apathy towards maintaining records, the Assam State Archives in Guwahati is an outlier.

All it took to change things around was one serious IAS officer with passion.

Jishnu Baruah, the former chief secretary of Assam, has always been interested in history. So, when a group of local historians — including Arnab Dey and Arupjyoti Saikia — approached the chief minister’s office in 2012 to discuss the dismal state of the archive, Baruah, then-Principal Secretary took matters into his hands.

“I happened to be in the right place at the right time,” says Baruah. “Nobody has any interest in the archives — but anybody with a little interest can make a big difference.” And what a difference his patronage made.

10 years later, the Assam State Archives is flourishing. It has found its way into the acknowledgements of several scholars’ books and has become a template for other archives to model themselves on. Researchers call it accessible and friendly, an anomaly among India’s smaller archives. The staff is engaged, trained, and motivated. Funds began to be allocated to the archive in 2013-14, so the building could be renovated with air conditioning and a conference room for events. Scribes were hired to help with documentation, and government offices were encouraged to send their records diligently to the archive. Assam is one of the few states in India to have stitched the importance of protecting public records into state legislation.

And under Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma, history in Assam has gained a new sheen with a digitisation drive, and the state government is amping up its plans for the archive.

“The story for scholars used to be one of harassment and frustration at the Assam State Archives,” says Baruah. “Today it is of acknowledgement,” referring to the number of authors who have appreciated the archive in their books of late.

Also read: ‘Whose history?’: In Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, the archives are fighting

The before and after

On the second floor of the building, a group of data entry operators patiently leaf through centuries-old documents, cataloguing them and noting their contents. On the ground floor, the digitisation of records is in full swing — the archive has 6,000 maps, a complete topography of the northeastern region, which has just been fully digitised. A few rooms across, Abdul, a staff member who retrieves documents for scholars and also works on preserving them, is currently laminating a document from the early 20th century.

The archive’s record three-storey stacks have recently been renovated. The entire area has gone through electrification, pest control, and has received a fresh lick of paint.

Arnab Kashyap, a lead archivist at the Assam State Archives, clears his throat and apologises for “the mess.” But there is barely any: he is referring to stray buckets of paint and neatly swept away debris. The building is tidy and well-maintained, and most of the records are carefully tucked away in cardboard boxes protecting them from humidity, dust, and light.

But it wasn’t always like this.

The archive was in “terrible shape” in 2012 when Baruah formally took charge. The files were not catalogued properly, and the building was falling apart. Baruah, who studied history at St. Stephen’s College of Delhi University, was already a frequent visitor to the archive — he has a particular interest in the British Raj and is working on his project on the evolution of the Indian Civil Services.

Calling it a lucky combination of various factors, Baruah was able to secure both funding and public interest in preserving archival history. He would bring his friends to the archive (He even convinced the chief minister to visit in 2014), organise exhibitions, and deliver lectures to students on the archive—just to bring it to public attention. If files got stuck in ministries, Baruah would help move them along to the archive.

He would always try to find a way to compile records through his various postings — like researching the history of the bureaucracy at the districts he was the collector of or encouraging members of the police force to compile cases of communal crimes and social tensions from village crime-notebooks maintained by colonial officers.

When he was posted as the collector of Jorhat district, he found one of the oldest files in the state in the district’s record room: papers pertaining to Robert Bruce, who was a Scottish trader responsible for introducing tea plantations to the region. During his posting as the collector in Haflong town of Dima Hasao district, he found two diaries of British district officers—dated 1938 and 1945—tucked away in an almirah among frayed papers. Breaking into a huge smile, Baruah raised his arms in victory while recollecting the moment, “I felt tremendous.”

Baruah’s passion for history was infectious. The current joint director of the archive, Mukul Das, even enrolled for a Master of Arts in History degree at Madras University in 2014 — two years after taking charge. Arnab Kashyap went to study archiving at the National Archives of India (NAI) in Delhi. One by one, junior members of staff are also going for further studies — Abdul is next in line to be trained in preserving records at NAI.

“This is a job that has to be taken up by someone who is interested. It cannot be done without passion,” says Baruah, while Kashyap and Das nod beside him.

Also read: Inside India’s shadow pharma industry — dingy drug units, cash payments, poor inspection

Keeping things going

The twin goal of any archive is not just to preserve records, but also to make them accessible to the public. Nobody knows an archive better than the archivists themselves but they also need to be patient and helpful while engaging with researchers. Without the right staff — which is the case in most Indian archives — research is an uphill, lonely battle with almost no support. Those who work at an archive are not just gatekeepers of knowledge, they are also responsible for its dissemination. Accessibility is key.

“The Assam State Archives are extremely accessible,” says Chinmay Tumbe, a professor at the Indian Institute of Management (IIM), Ahmedabad. “They’ve made it easy — the digital footprint is nice. The library is usually an understated part of an archive, but as precious — the fact that their catalogue is online is fantastic.”

Tumbe is responsible for setting up the IIM-A Archives, which had him visit archives all over India. In fact, he visited the archive in Guwahati to learn more. His takeaway is to hire a few more interns or research assistants to recreate the helpful environment in Guwahati.

The Assam State Archives has 26 permanent employees, and other members of staff are hired on a contract basis. The permanent staff are patient and involved with their work: they mill around the archive, keen to offer their services to scholars. Unlike most other government offices, they don’t have a fixed lunch break: they eat lunch when their schedule permits.

The archive has a popular internship programme for college students, which started in 2015. Though unpaid, the four-week internship includes record sorting, listing, and retrieving as well as time spent in the library, the research room, and reprography room.

In December 2022, the archive received 20 applications. Earlier this week, Kashyap received a call from a commerce student — but he’s used to interest from a diverse group of students. Das also personally maintains a Facebook page for the archive, regularly uploading historical facts and photos to its 3,500 followers, which increases the archive’s reach, and makes it part of public conversations.

A Facebook post on Dibrugarh’s Assam Medical College, the oldest medical institution in the northeast, drew over a hundred likes and 27 shares. The post includes images of a 1,900-page document outlining the rules for the regulation of the college. Most comments thank the archive for the information or are about the importance of preserving such records. In May 2021, during the peak of the pandemic in India, the Facebook page shared the colonial government’s preliminary report on the influenza pandemic of 1918 in India.

When Baruah retired as chief secretary of Assam in August 2022, the Facebook page shared a special post. “We will always remember his contribution to the Assam State Archives,” Das wrote in the post.

Even those employees who aren’t interested in history have found things to appreciate. Three data entry operators were recently employed contractually in November 2022. None of them has a background in history: two are BTech graduates, while the third studied biotechnology. Their job is to painstakingly go through old records and catalogue them for future digitisation.

“The best part about working here is the handwriting, actually,” says Meenakshi Deka. She enjoys reading colonial calligraphy but admits that she doesn’t understand the context of most of what she goes through.

“In a way, it’s a double-edged sword. The writing is beautiful but difficult to read sometimes. It’s the opposite of what I thought I would be doing as a data-entry operator, but it’s still interesting,” adds her colleague Jyotish Majumdar.

Not too far away, Abdul pulls out records to take to scholars in the research room downstairs. He has been employed at the archive since 2015 and has now become a recognisable fixture, often going far beyond his job description. He checks in with scholars throughout the day, retrieving and returning their records to the stacks. He also spends a couple of hours a day laminating old documents by hand with tissue paper — a finicky task that involves sandwiching an old document between two sheets of sturdy paper and using adhesive to keep it in place. This keeps the original document from decaying further, but also ensures that both sides of the document are visible. After some research and consideration, it was decided that lamination would preserve records better than chiffon, which was earlier in use — Abdul and Kashyap say that chiffon is useful for mass storage of old documents, but is not as good at preserving the integrity of each page.

The Assam State Archives even has its own publications. Its most recent monograph, published in 2020, is an edited volume titled Tour Diary of Naga Hills District, which features excerpts from a diary by J.H. Hutton, the colonial deputy commissioner of the Naga Hills between 1921 and 1934.

While their website has a full catalogue online — an unusual but helpful practice that gives a researcher a clear picture of what’s available when they visit — all the documents are not yet digitised. They don’t have enough funds for this yet, according to Kashyap. While the chief minister has announced funding, it is yet to come through. So far, only maps have been fully digitised.

“Despite limitations, the Assam State Archives is surely better managed compared to what it was in the last century,” says Saikia. “ It has shown how better archival management can truly make such places a welcome experience.”

And this welcome experience at the archives is certainly not underappreciated by academics and students. But they also have suggestions for its improvement.

“With its limited resources, the archive is still doing well. The next thing the archive should look at preserving is oral history,” says Prof. Barnali Sharma, who teaches at Guwahati University. Tumbe agrees: an oral history repository and collections of private papers are certainly something the archive can build on.

Scholars call a comparison to global standards like the British Library unfair — due to the completely different scales of operation and the volume of visitors.

“Even then, the Assam State Archives could certainly recruit more people to do the work of delivering the records to the research room,” says Tanmoy Sharma whose dissertation at Yale has led him to archives across the world. He added that all records should be thoroughly examined so that their catalogue description matches their physical location.

“Also, the ASA should try to get some of the records moved from the district record rooms across Assam to the repository in Guwahati,” says Sharma. “This will be a way of preserving tons of files that would otherwise soon fade into the dust of history.”

Despite the lag on the digitisation front, Tumbe agrees that the Assam State Archives offer some valuable lessons to other archives that are in desperate need of refurbishment.

“It shows that you don’t need too much money to create a nice atmosphere in an archive, and to welcome researchers and not make it an intimidating space, like the National Archives of India in Delhi,” he says.

Also read: Goa Police said Felix Dahl died doing cartwheels. 8 yrs later, ‘murder’ probe still on

The next frontier

The next frontier for the Assam State Archives is getting its district record rooms in order.

Undivided Assam had 10 districts — which today includes five of the seven Northeast states — and each district had a record room. Most of these record rooms have old colonial files pertaining to the administration of the region and its unique terrain.

“Because of the primacy of the district as a unit of governance, it was natural that the district courts became the custodian of all official correspondences,” says Saikia.

He adds that these records are still important. “Their range can be truly widespread: a petition from a poor villager, a report prepared by the district magistrate, or a judicial paper. The list is rather long. Unfortunately, most records in these district record rooms are not arranged and preserved according to standard archival practices. There are few rare instances where things are in good shape,” says Saikia.

Baruah did try to tackle the issue and took up projects to spruce up the records rooms in the districts of Dibrugarh and Jorhat. The files were catalogued and the research facilities were improved.

“I have tried to get some records from the Jorhat record room to Guwahati. Some files were transferred, but not all,” says Baruah. “It’s a painstaking job. And districts are often reluctant to part with their files because they see it as their history.”

And perhaps it would be wiser, in the long run, to move these records to Assam, added Saikia.

But it’s still an uphill battle. The silver lining is the interest of the current BJP government in Assam seems to have been sustained.

According to Das and Kashyap, CM Himanta Biswa Sarma, has allocated Rs 1 crore a year towards digitisation. Biswa also announced in September 2022 that all land records would be digitised by 2023.

Much of the government’s work is uploaded digitally, and a portion of contemporary files have already been sent to a temporary record room. Soon, they will make their last, perilous journey to their ultimate destination: the Assam State Archives.

This article is part of a series on the state of India’s archives. Read all articles here.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)