Before hashtag feminism, MeToo and intersectionality, five Indian feminists zeroed in on the unlikeliest of starting points that kickstarted their second wave of women’s movement.

It was a government committee report.

“The 1975 Committee on the Status of Women report woke us up to the harsh reality of the field and opened our eyes to the issues that existed of exploitation and power dynamics, particularly the declining sex ratio,” said Rami Chhabra, columnist and founder–president at Streebal, an NGO for women.

This paper emphasised exclusionary sociocultural norms and the political and economic processes that marginalised Indian women. It was credited with laying the groundwork for women’s movement in Independent India, highlighting discriminatory practices and paving the way for gender-sensitive and inclusive policy-making in the country.

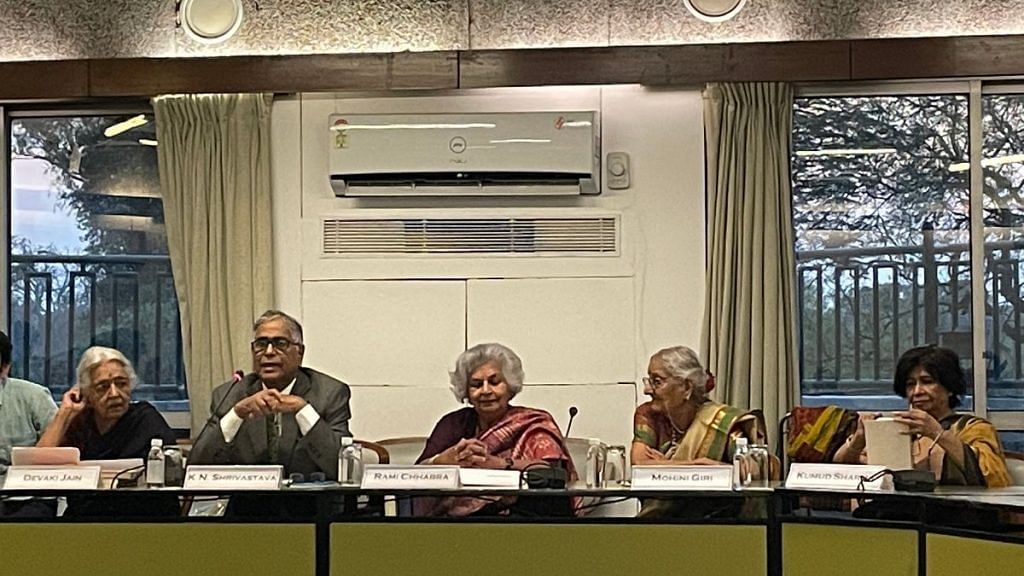

As warm yellow lights danced off their faces, the five women, now in their 80s, sat around a table at a recent event at Delhi’s India International Centre. Brimming with nostalgic stories, they recalled their contribution to the 1970s Women’s Movement in India. This powerful campaign focused on fighting dowry, sex-selective abortions and custodial rape, among other pressing issues. Surrounded by friends who had joined them all those years ago, along with young women looking for inspiration, the speakers narrated tales from a difficult era in history, one where they championed the “unsung cause” that is women’s rights.

Also read:

The report that changed everything

Vina Mazumdar, one of the heads of the Committee on the Status of Women, kept the report hidden in her own home, away from the prying eyes of journalists and other curious characters. That was, however, only until Chhabra, then a journalist, waded into Mazumdar’s house after receiving a tip. She examined the 1,000-page report over many gruelling evenings, with crispy hot samosas for replenishment and support.

“Like any other journalistic exposé today, I was able to bring out the highlights of the report. And once it was out, it had to be tabled in Parliament, coming into the purview of the public,” she says.

And once the curiosity of Chabbra and her various other “comrades and sisters” was piqued, they combined their individual strengths and personal agendas to promote the greater good.

Also read:

The fight to champion women’s rights

While these women shared laughs over their ages, mothers-in-law and facing sexist comments at the workplace, they also discussed their experiences working for women’s rights across various verticals. From journalism and social work to economics, they made their individuality shine in each sector despite the many hurdles in their path.

“The idea of invisible workers, of women being workers and not being recognised as such, inspired me to go into the field and work alongside the Indian Council of Social Science Research,” said Devaki Jain, development economist and founder at the Indian Institute of Social Studies. She studied activities that women and men participated in, in rural India. “And that helped me realise the gainful activities that women were doing but were never counted economically.”

Mohini Giri, former chair of the National Commission for Women, often took up Herculean tasks at the grassroots level. From fighting for female representation in Panchayati Raj institutions and preventing dowry deaths to representing women at various conferences, Giri’s life has been dotted with remarkable experiences, testimony to a life led with strength, courage and endurance.

“My social work began in an ashram in Rishikesh, and that helped me find my cause. I met [Army] Jawans, who told me not to care about them but take care of their families instead. And that’s how I got into the movement,” said Giri while discussing her work at the War Widows Association.

Also read:

Wins and losses

The smiling speakers soon entranced audience members with their stories and conversations. A big part of women’s rights entails child care, for women’s and children’s lives are often heavily intertwined. And Devika Singh, who was a professor around 1969, shifted her gaze to the lives of the children of migrant workers and labourers.

“I found my calling when I saw the unfortunate children on the streets outside Loreto College in Kolkata. The struggle of Partition and bloodshed was blaring in my eyes. And thus, I wanted to work with children because I could not see them like that anymore,” said Singh, who is also the co-founder of Mobile Creches, a childcare development initiative.

Everyone lauded Mobile Creches’ work with the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), in launching daycare centres at worksites in Maharashtra. “It went beyond just social services and was a workable model,” said Jain.

These remarkable women took their fight to the policy level too. Kumud Sharma, chair at the Centre for Women’s Development Studies, dabbled in various institutions as a researcher, calling it a “momentous journey” filled with setbacks.

“Only in 1992, women received the right to participate in the Panchayati Raj. It took the government two and a half decades to give women that, and see to it that the voices of the marginalised reached the public,” said Sharma.

As the discussion veered toward the present state of affairs, a cloud of doom engulfed the once lively room, a gripping silence broken by Giri’s passionate remarks.

“No matter our struggles then, I still do not think men and women are politically equal even today. My only regret is that in my career of 65 years, I have still not been able to change the mindset of men. If we could, then all other issues would disappear.”

There was a smattering of weak laughter, but most of the audience looked on with hopeless eyes.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)