Srinagar: Ahmed from Pulwama grew up in a world without cinema halls. He didn’t know the magic of giant movie screenings in darkened halls. Still, he has had a Bollywood favourite of his own. A die-hard Saif Ali Khan fan, he has managed to download and watch movies on computers and phones over the years.

So, when an INOX multiplex opened in Srinagar this month, that too with Saif Ali Khan and Hrithik Roshan-starrer Vikram Vedha, he just had to go for it. He even delayed attending his cousin’s wedding. But Ahmed just wasn’t prepared for the experience of watching a film in Srinagar’s first multiplex cinema. The 23-year-old sat through the action scenes with his fingers stuck into his ears. “The audio,” he exclaimed, “was just too loud.”

An entire generation of Kashmiris has grown up without something that the rest of India takes for granted — going to the cinemas. Three decades of armed conflict, Islamist threats, and bombings have kept movies out of Kashmir, shrunk public space, and pushed people indoors. Now, that’s set to change. It’s also ironic that the heavily guarded INOX multiplex has opened when cinemas are losing out to OTTs across India as viewing behaviour changes.

But a cinema hall in Kashmir isn’t just about entertainment and viewing habits. It is a tug of war between the conflict ecosystem and that elusive Kashmiri fragrance called ‘normalcy’. If it sells tickets, the government and the cinema owner hope, viewers will be voting with their feet against years of cyclical violence.

Ahmed’s father was initially hesitant to give him permission to watch the film even though the INOX cinema is in the high-security zone of Badami Bagh Cantonment, which also houses the Army’s Chinar or XV Corps. It’s right behind Broadway Cinema, a relic of the ’90s. Today, the building houses a bank, and the smell of popcorn lingers only in the memories of those who are old enough to remember.

“I’ve seen all of Saif Ali Khan’s films. I wanted to witness the first show on the big screen,” Ahmed says.

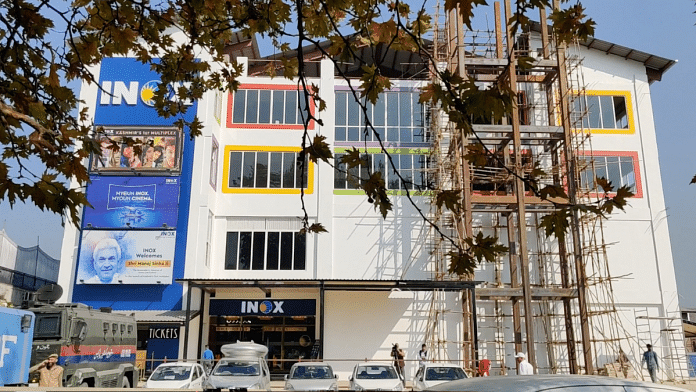

A large hoarding welcoming Jammu and Kashmir Lt Governor Manoj Sinha still dominates the four-storeyed multiplex building. An armoured truck, stationed near the entry gate, with at least a dozen policemen, and an elevated security tower next to the ticket counter only underscore the strangeness of the situation.

On 1 October, barely 23 people watched the first screening of Vikram Vedha, while Mani Ratnam’s Ponniyin Selvan: 1 saw about 30 seats filled. Each of the three screens in the multiplex can seat 522 people.

Inured to the presence of security, Ahmed enjoyed his first theatre experience. As the last shot faded into the credit roll, he was elated because of “Saif’s acting, movie plot, and action”. While leaving the hall, a group of students from the National Institute of Technology (NIT), Srinagar, asked: “Are there Kashmiris here in the hall?” When a few local residents nodded, the students clapped and cheered for them.

The camaraderie is a far cry from the fear that dominated theatres three decades ago.

A fight for legacy

On 20 July 1989, a bomb exploded in the women’s washroom at Khayam Cinema in Sringar’s Munawar Abad. A month later, on 18 August, an armed outfit called Allah Tigers gave a call to shut down cinemas, beauty parlour, and liquor shops in Kashmir. In the weeks that followed, there was uncertainty across the region, especially in recreational areas like cinemas.

Members of Allah Tigers marched on the roads, threatening hoteliers and liquor shop owners, demanding that they stop serving alcohol. They put restrictions on women’s clothing too, besides taking it upon themselves to censor video tapes available to the public in shops and lending libraries.

And finally, on 1 January 1990, the cinemas went silent. All 15 of them across Kashmir, nine in Srinagar alone, closed their doors to the public. And just like that, a more-than-half-a-century-old cinema culture died.

“We couldn’t believe something of this enormity could ever happen in Kashmir,” 65-year-old Manmohan Singh Gauri the proprietor of Palladium Cinema — earlier known as Kashmir Talkies — at Lal Chowk. Gauri was somewhat convinced that the ‘ban’ would be temporary. “So we left everything as it was, assuming that we would return and resume business.”

He never could. In 1993, militants set off explosives on the premises. The resulting fire consumed the adjacent building as well. “We did not even get a chance to lock our cinema halls properly,” Gauri adds.

All he was left with were carefully documented photographs of the cinema in its glory days—and newspaper clips of its charred ruins. He arranges them on a coffee table neatly. There’s a photograph of his grandfather, Bhai Anant Singh Gauri, greeting the former Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad, with folded hands.

The fate of Kashmir Talkies, a historic cinema that was the beating heart of Srinagar after Partition, is a tragedy far greater than any Bollywood saga. Jawaharlal Nehru made his famous 1948 speech in front of it. Bhai Anant Singh established it at Lal Chowk in 1932 and later renamed it Palladium Cinema. Over the decades, as a nascent film industry spread its wings, Palladium Cinema screened some of the biggest Bollywood hits — Man Ki Jeet (1944), Bobby (1973), Amar Akbar Anthony (1977), and Dharam Veer (1977). Rajesh Khanna’s Maha Badmaash (1977) was the last movie to be screened in Palladium cinema on 31 December 1989.

“We used to have a great market for English films as well. Hollywood films would be screened here simultaneously with Mumbai, and most of the times before Delhi,” says Gauri.

Today, Palladium Cinema houses a Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) bunker, its perimeter surrounded by barbed wire. Gauri, who shuttles between Amritsar and Srinagar, despairs over the state of his family’s cinema. He migrated to Amritsar in January 1990 after the Kashmir Cinema Association decided to shut down all theatres. When he’s in Srinagar, he stays in his family house inside Badami Bagh Cantonment’s Sonwar. Now, he wants to revive his cinema but is facing an issue over the lease with the revenue department.

“This government has often said that they want to resettle the migrants of militancy. I have been pleading with them to resettle me, but no one is bothered,” Gauri says.

Many theatres that fell silent were turned into Army camps. Others were torn down to make space for newer buildings; a few were converted into other businesses. Anantnag’s Nishat Talkies was demolished only to make space for a shopping complex. Broadway Cinema building now houses Jammu and Kashmir Bank, and Khayam Cinema is a super-speciality hospital called Khyber Medical Institute.

But Firdous and Shah cinemas, which were occupied by the CRPF, are silent memorials of a happier past. At Firdous, a cash register lies open on a table, its page turned to 11 December 1985. Records show that Khoon Ka Badla Khoon (1978) was screened that day. Film spools are strewn on the floor as rusted projects stand as silent sentinels.

Also read: There’s a new Hindu-Muslim conflict in Kashmir—this time over one language, two scripts

Taste for films in Kashmir

The militant Allah Tigers may have broken the back of theatres in Kashmir, but it could not stamp out the love for movies so deeply ingrained in the Valley’s culture.

“After cinemas were forced to shut down, people turned to VCRs, VCDs, and then DVDs. Later, with the internet, they started downloading films. When Doordarshan aired films on weekends, the markets would be empty of people,” says Ibrahim Wani from the social science department of Kashmir University.

Love for movies dominated wedding celebrations. Actors were characters in traditional wedding songs. When a groom arrived, people would roar, “Aaw hi aaw hi Rajesh Khana (Here comes Rajesh Khanna — the groom).”

Dilip Kumar, Kamini Kaushal, Nargis, and Dev Anand, among other stars, were household names. “Most of Dilip Kumar’s movies used to be tragedies. So, when we came home from Palladium or Ambrish, our eyes would be red because of crying. Mother would scold us, asking if we went for entertainment or to shed tears,” says Neerja Mattoo, former principal of Women’s College, Srinagar.

To attract larger audiences for English films, cinema proprietors would translate film names on posters to Urdu. The Three Musketeers (1973) became ‘Teen Ha*amza**’ and The Brothers Karamazov (1958) became ‘Kamraj Ke Bhai’.

“Once, my grandfather took my grandmother to see Ram Rajya (1943), and we also tagged along. When Sita ji appeared, my grandmother bowed to the screen,” says Mattoo, bursting into peals of laughter. And when the 1968 Iranian film Khana-e-Khuda, or ‘House of God’, was screened, patrons took off their footwear at cinema doors. “When we saw people performing tawaaf (circumambulating the Kaaba at Mecca), I felt close to God. Everyone — men, women, and children — came out of their homes to watch the film. We have cried watching it,” says 65-year-old Mohammad Abdullah Kallu from Anantnag.

In March 2019, the CRPF tried to revive one of the cinemas called Heaven, which it had occupied after militants lobbed grenades inside it in 1991. But the experiment was a failure. Footfalls remained low.

Cinemas at crosshairs

There was always an undercurrent of tension woven into Kashmir’s love for movies, with a strain of conservatism among a section of Muslims claiming that Islam prohibits clicking pictures, shooting videos, and painting.

During the 1930s and 1940s, it was mainly women from Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh bureaucratic and business families who patronised theatres. “Moviegoers in the Valley started to get a bad reputation. They were called ‘talkies’ to belittle them,” says Mohammad Amin Bhat, playwright and president of Adbee Markaz Kamraz, a cultural organisation. Some parents would make sure not to marry off their daughter to a ‘cinema fan’. However, a new Muslim middle class emerged in the wake of former J&K Prime Minister Sheikh Abdullah’s land reforms in 1953. Separate galleries for women were introduced in cinema halls.

In the political hotbed that was Jammu and Kashmir, cinemas made people socialise in greater numbers other than religious congregations. It was a world away from the traumatic memories of Partition and Operation Gulmarg in 1947.

Palladium Cinema became important to Sheikh Abdullah who led the Emergency administration and the Peace Brigade after Maharaja Hari Singh fled to Jammu on 26 October in the wake of the invasion. A red flag with a plough symbol was installed on the cinema premises. The same flag would later become the National Conference’s elections symbol. Palladium Cinema became an operation centre for the Peace Brigade during the Army-led anti-tribal offensive. Later, it housed a large picture of Sheikh Abdullah riding a horse with the flag in his hand.

Slogans resounded within the cinema’s walls. There were proclamations of Hindu, Muslim, Sikh unity: “Sher-e-Kashmir ka kya irshad, Hindu, Muslim, Sikh itehaad” (What does the lion of Kashmir want? Hindu, Muslim, Sikh unity), Hamlawar khabardar, hum Kashmiri hain tayyar (Beware oh conquerors—we Kashmiris are ready to fight), Kadam kadam badenge hum, mahaz pe ladenge hum (We will march forward, we will fight at the front).

After Sheikh Abdullah’s arrest in 1953 and the subsequent political turmoil in Jammu & Kashmir, the National Conference flag at the cinema was removed. It was replaced with black flags during the push for a plebiscite, the 1963 Hazratbal Shrine theft, and other political agitations. In his book, My Frozen Turbulence in Kashmir, former J&K governor Jagmohan Malhotra writes that when the holy relic, believed to be a strand from the beard of Prophet Muhammad, went missing from Hazratbal Shrine in 1963, protesters burnt down a cinema and hotel owned by the brother of Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad.

In 1985, the Anthony Quinn-starrer Lion of Desert (1980), a film based on the Libyan anti-colonial revolutionary Omar al-Mukhtar who did not compromise with Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, was released in Kashmir. People raised slogans against Sheikh Abdullah, tore the hoardings with his pictures, and blamed him for the “enormous sacrifices of Kashmiris for his lust for power”. The movie was banned instantly.

If films fed the dreams and hopes of the people of Kashmir, then the cinema halls became targets of terror. Even before it was finally burned down in 1993, Palladium Cinema was a ripe choice for militant groups. Gauri has all the dates jotted down in a file. On 12 December 1983, a crude bomb was found in the premises of the cinema, he says. And Palladium wasn’t the only target. A few proprietors defied the ’90s ban. They tried to reopen it and paid a hefty price too.

Also read: Bollywood isn’t dead. But there’s panic everywhere in Mumbai

Revival of cinema

Back in 1998, then-Chief Minister Farooq Abdullah tried to revive cinemas by offering Rs 32 lakh as a cash subsidy to theatre owners. Regal Cinema, Neelam Cinema, and Broadway Cinema in Srinagar defied the threats from militants and opened their doors again. But in September 1999, militants hurled a grenade at Regal Cinema, killing one and injuring many.

In September 2005, during a screening of Aamir Khan’s Mangal Pandey: The Rising, militants attacked Neelam Cinema. Seventy people trapped inside were rescued by staff and police. One militant was killed. Gradually, Neelam Cinema’s business plummeted due to heavy security checks and threats from militants, and it finally closed permanently in May 2010. Broadway Cinema shut shop as well.

Now, after a gap of 12 years, theatres are back in Kashmir. The most prominent is the four-storeyed multiplex—a shining symbol of the Indian film industry. It was inaugurated on 20 September 2022 with much fanfare by L-G Manoj Sinha. Two days prior, he inaugurated “multipurpose cinema halls” in South Kashmir’s Pulwama and Shopian.

“A couple of years ago, we realised that there aren’t any outlets for wholesome family entertainment. We sifted through some ideas and realised we have a relationship with cinema in Kashmir. My father used to run Broadway Cinema,” says Vikas Dhar, owner of the INOX multiplex.

Staff—comprising mainly local residents—were trained for various jobs. “We’ve got chefs, projectionists, operational associates from Delhi and Amritsar to train local staff,” says Neeraj Saddi, INOX housekeeping in-charge.

Kashmir in Films

From Kashmir Ki Kali (1964) to Bobby (1973) to Bemisal (1982), Kashmir has been a muse for many Bollywood films. When Mani Ratnam’s Roja was released in 1993, it evoked a feeling of patriotism in the audience — people could relate to the 18-year-old Tamilian woman (played by Madhoo) who searches for her husband kidnapped by militants in the Valley.

“Not whistles and comments on the heroine, but displays of ‘nationalistic’ fervour,” wrote Tejaswini Niranjana in EPW. “The response is enabled in part by identifying the nation with the heroine, who is then alternately motherland and lover/devoted wife.”

The film won three National Film Awards, including Best Film on National Integration. But it also started the trend of “good Hindu and bad Muslims” stereotype in the Hindi film industry.

It was Mani Ratnam’s Ponniyin Selvan: 1, which INOX Srinagar decided to screen on the first day along with Vikram Vedha. The former did not get as much footfall in October 2022 as Roja had in November 1993.

Bashir Bhawani, actor and chairperson of the Ensemble Kashmir Theatre Akademi (EKTA), pointed out that the Valley was treated as a honeymoon destination with local residents depicted as “naive”. Former college principal Mattoo agrees: “Most of the filmmakers from Mumbai and Delhi viewed Kashmir as a glamorous and romantic place, while Kashmiris were innocent. We might call it in modern critical terminology as an imperialistic narrative.”

When Jab Jab Phool Khile (1965) was released, Kashmir saw an abrupt rise in tourist rush from mainland India. “No director showed cultural heritage; local sensibilities were never shown. We have a 5,000-year-old recorded history, but nothing on that front,” Bhawani says.

After 2010, when movie shooting resumed in Kashmir, there was a change of sorts in this popular narrative. “We saw director Vishal Bhardwaj’s Haidar (2014) with such a stark reality of Kashmir that it made history. We saw Bajrangi Bhaijaan (2015), which showed the pain of separated Kashmir,” he adds.

Most recently, Vivek Agnihotri’s The Kashmir Files also made huge headlines because of its ‘one-sided portrayals’ of Kashmiri Pandits and their suffering. PM Modi said: “Through such films, people come to know about the truth and understand who was responsible for any incidents in the past. Who exploited or who did the correct thing, films like these try to project.”

Small screens in small towns

Although the government wants to bring the magic of films back into Kashmir, the move comes at a time when OTT platforms are nipping at the film industry’s heels.

Sinha called it “a historic day for J&K UT” when he inaugurated the 70-seater “multipurpose” screens in Pulwama and Shopian. The administration has awarded the contract to run these small screens to a Chennai-based start-up, Jadooz.

“We intend to open 25 small screens in Jammu and Kashmir by December 2023, 12 of which will be in Kashmir alone,” says Rahul Nehra, founder and managing director of Jadooz. “We are optimistic about the participation of people.”

Jadooz claims it will release films in time with other large screens. But the big question is — will people return to the cinema? In Shopian, residents are anxious. And there’s always Amazon Prime Video, Netflix, and other OTTs.

The cinema revival is a meeting point, a convergence of decades of conflict with a new age where films can be streamed online. For 28-year-old Sohail from Shopian, the charm of cinemas is rapidly eroding. “Almost all of us have 72-inch TV screens at homes with OTT subscriptions. Why would we go out and see a movie?”

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)