New Delhi: The journey of pashmina — the fine, luxurious wool — cherished all over the world, starts in the cold deserts of Ladakh, where families of shepherds and goatherds raise a breed of goat called Changthangi or Changra through the harsh winters, hoping to harvest the soft cashmere in spring.

Co-existing for centuries in the same landscape is Canis lupus, the Himalayan grey wolf that preys on the domesticated pashmina goats.

To protect themselves against significant economic losses, local communities for centuries have developed a unique tradition. Digging conical pits called shandong, families place a sacrificial live goat inside to attract a wolf. Once trapped, the wolf is stoned to death.

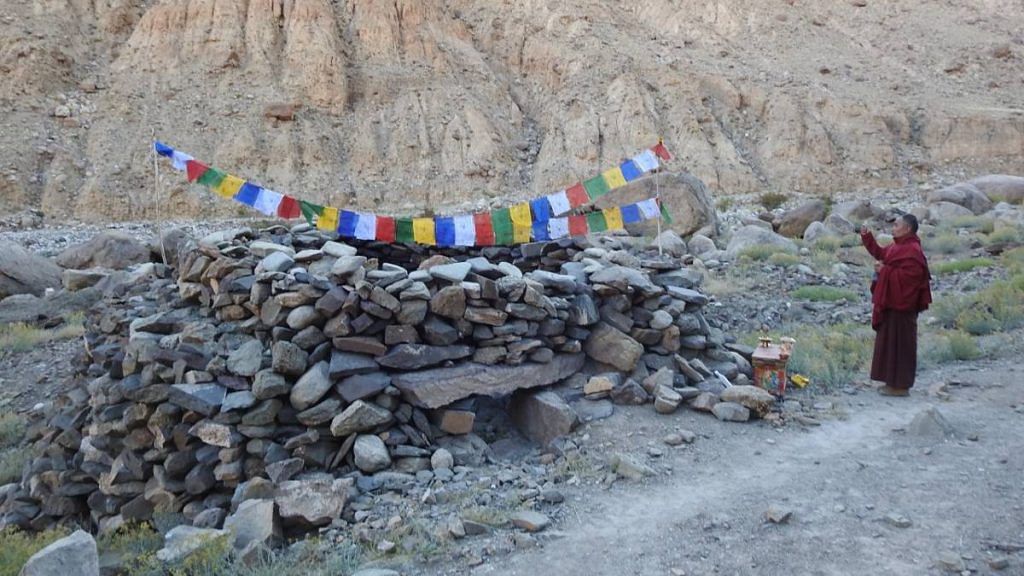

For more than two decades now, however, a team of conservationists have slowly been turning these animal traps into religious sites — by putting up Buddhist stupas at the shandong sites — to discourage the community from killing a species they have been in conflict with for centuries.

“Although human societies and wolves have been interacting for centuries, wolves are considered to be a menace throughout the world. Be it stories like Little Red Riding Hood, or Bollywood movies, the global perception of wolves is that they are vermin,” said Kulbhushansingh R. Suryawanshi, a scientist working with the Nature Conservation Foundation, a Mysore-based NGO.

As a result, the species is always hunted, contributing to its dwindling numbers globally. Wolves are almost as endangered in India as tigers, with just about 3,100 animals left in the country, according to a 2022 report by the Wildlife Institute of India.

“We wanted to address the issue without victimising an already marginalised society (the shepherds). For over 20 years, we have been closely working with the communities.” Suryawanshi told ThePrint.

Earlier this year, the team’s work was described in a study published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.

Also read: From January to June, wildlife board gave permits that can be ‘disastrous’ for protected areas

Turning traps to memorials

Since the 1960s, Ladakh has had a strong military presence, which has facilitated the expansion of the road network. The region opened for tourism in 1974, with particularly rapid growth in the past two decades, according to the research team.

The expansion of defence, tourism, and developmental infrastructure has disturbed the ecological balance of the area, resulting in the decline of prey animals like the Tibetan antelope and Tibetan gazelle, which in turn directly affected the populations of black wolves.

When the team started their work in the area, they began by carrying out a survey to identify active shandongs in a restricted region. The three blocks they selected — Changthang, Rong, and Sham — were those where wolves were common and had negative interactions with people.

The surveys involved visiting 64 villages in the study area and interacting with key local informants to map the locations of all the shandongs. The team noted that identifying active shandongs was difficult, since hunting wolves is illegal in India.

The team found that 37 shandongs had been used within the past decade, of which fifteen were still active.

In 2017, the team initiated discussions with members of the local community in the village of Chushul, and their political representatives, about the possibility of neutralising their shandong. However, instead of destroying them, the team wanted to preserve and maintain them as part of the cultural heritage.

Bakula Rangdol Nyima Rinpoche, an influential and revered monk in the area. suggested establishing Buddhist stupas at the shandong sites.

“When we approached the (other) monks with the idea, they were very happy. They said that it would be a symbol of atoning for past sins,” said Suryawanshi.

Religious sentiments acted as a stronger deterrent than the merits of ecological conservation would have.

In the study, the team wrote that the local communities have revealed considerable pride and a sense of gratification for having been involved in this initiative, and that it has made a sustainable impact in terms of renewed support for wolf conservation.

The 40-year-wait for atonement

One of the locals involved in the project is Karma Sonam, a field manager with the Nature Conservation Foundation.

Sonam, who grew up in a pastoral family, was 10 years old when, while running an errand with his father, the two noticed a small crowd gathered around a shandong.

A wolf was trapped in the shandong, and the villagers asked the two to join them and help kill it. Sonam watched the men stone the wolf, and eventually joined in himself till the trapped animal died.

The incident stayed in his memory. Although Sonam wanted the village to stop killing the wolves this way, the local community were not going to listen to anyone about conserving animals that were a huge threat to their livelihoods, he explains.

Almost 40 years later however, Sonam says he got this golden opportunity to atone for his sins.

He says that now, one can see offerings around these stupas, indicating that the community in general has now accepted and committed to this practice.

“Because we involved religious sentiments in conservation, even the older generation — which has been at conflict with wolves for the longest — accepted the change,” he said.

The team is now planning to expand the practice to other areas in Ladakh.

(Edited by Poulomi Banerjee)

Also read: Why exotic snakehead fish is under threat — people want them as aquarium pets, 6x rise in trade