New Delhi: India’s pathway to net-zero emissions should focus on decarbonising “more difficult” sectors like cement production and transport, and not just power, Tim Gould, chief energy economist at the International Energy Agency has said.

The IEA is working in partnership with the NITI Aayog to help India achieve it’s net-zero emissions targets and clean energy transition.

Decarbonisation refers to the process of removing or reducing the carbon dioxide output. Heavy industries like cement and steel making are difficult to decarbonise because carbon emissions are part of the production process.

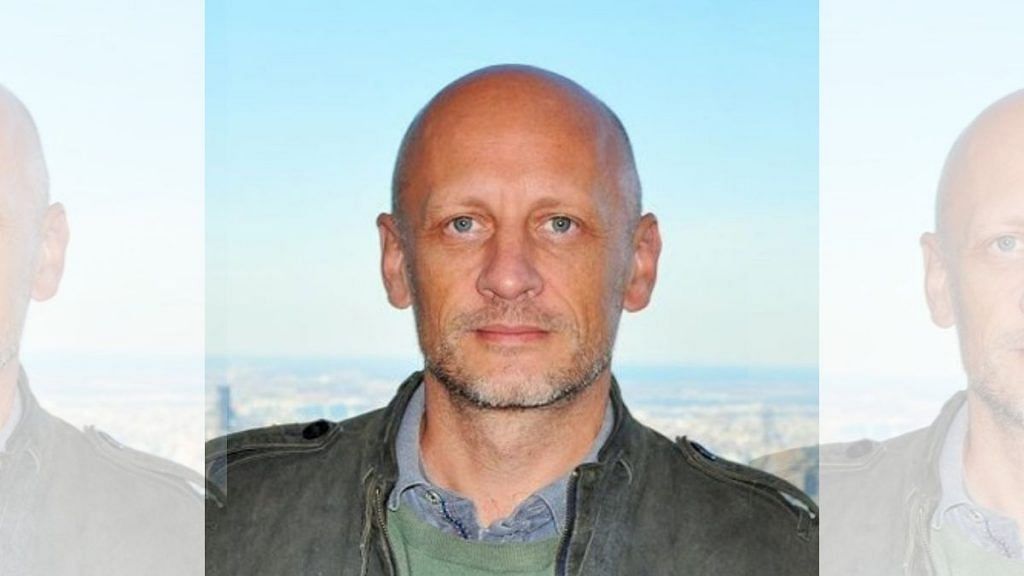

In an interview with ThePrint, Gould said India would need to chart its own path to net-zero emissions by 2070, a goal it had announced at the COP26 climate change conference in Glasgow earlier in November.

“We need to be very aware that the discussion about India’s pathway to net zero (emissions) cannot just be a discussion about what happens to the power sector,” said Gould.

Referring to the IEA projections, he added, “in our own modelling, most of the growth in emissions would not come from the power sector, it would come from industry, it would come from transport, particularly from freight. We need to be thinking about the opportunities to introduce low carbon technologies in some of these much more difficult areas.”

India is the third largest emitter of greenhouse gases (after China and the US), and the second biggest producer of coal in the world. About 70 per cent of the country’s electricity generation is dependent on coal.

In light of this, India’s net-zero emissions commitment is particularly significant, Gould said.

“What we’re seeing with the Indian announcement is the prospect of a kind of new model of economic development that could avoid the carbon intensive approaches that many countries have pursued in the past,” Gould said. “So it’s significant for India. But it’s hugely significant also for what it implies as a sort of brute blueprint for other developing economies.”

Also read: India’s transition from coal will be ‘messy & complicated, affect 2 crore people’, says study

‘Energy sector must take responsibility for emissions’

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (a UN body that scientifically assesses the status of climate change), the world must achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels. The Glasgow Climate Pact, adopted at the COP26, also seeks to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to achieve this goal.

Negotiations at the COP26 about ways to reduce emissions threw up a host of possible methods to achieve this — transitioning to renewable energy, creating carbon sinks (such as planting forests), as well as carbon capture and storage from the atmosphere. However, the efficacy of both carbon sinks in the form of large scale tree plantations and carbon capture and storage units has been questionable so far.

Gould said the IEA was “skeptical” of solutions for reducing emissions that are not coming from within the energy sector.

“We think it’s incumbent upon the energy sector to take responsibility for its own emissions. And we need to think about the solutions that can come from within the sector. So we are naturally quite skeptical of either country, or corporate commitments that seem to rely heavily on offsets from outside the energy sector,” he said. “We believe that there are technologies available to tackle many of those emissions.”

Also read: What is the Glasgow Climate Pact & why India did not commit to coal phase out

The costs of meeting climate goals

Globally, the amount being spent on clean energy projects is $1 trillion, according to Gould, who added that this amount was “well short” of what is needed to keep the “1.5 degree above pre-industrial levels” goal alive.

At the COP26, PM Modi had also said that developed countries must deliver $1.3 trillion as climate finance so that developing countries can achieve their goals.

“By the end of this decade, and in our view, we would need to see more than triple that amount ($1 trillion) being spent on not just renewables, but on energy efficiency on EVs on new infrastructure,” Gould said.

“We’re very focused at the IEA on trying to think through what are the barriers to those kinds of investments. What are the barriers to those capital flows both within a domestic system and internationally? You know, how can we bring more capital into that clean energy transition? Because I think that’s the defining challenge for the next few years,” he added.

(Edited by Poulomi Banerjee)

Also read: Why climate finance is a big deal, and where negotiations have reached at Glasgow COP26