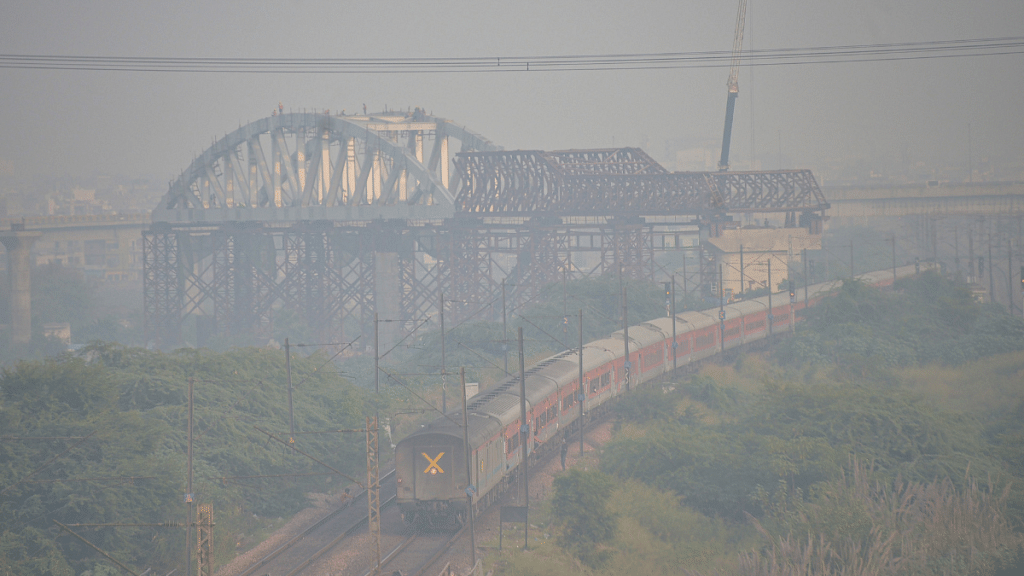

New Delhi: Air pollution is reducing the life expectancy of Indians by as much as five years — the highest health burden in the world — according to the latest edition of the Air Quality Life Index (AQLI), produced by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago.

The index, which is based on data from 2020, points out that 63 per cent of India’s population lives in places where air pollution levels “exceed the country’s own national air quality standard of 40 µg/m3 (micrograms per cubic metre)”.

At an international level, this spells even worse news. “Since 2013, about 44 per cent of the world’s increase in pollution has come from India, where the particulate pollution level has increased from 53 µg/m3 then, to 56 μg/m3 today — roughly 11 times higher than the WHO guideline,” says the index, which was released Tuesday.

The index notes that India’s National Clean Air Programme (NCAP), a strategy launched in 2019 to reduce air pollution across 122 non-compliant cities, has the potential to save 1.6 years of life.

However, the NCAP’s goal of reducing harmful particulate matter (PM 2.5 and PM10) levels by 20-30 per cent by 2024 (compared to 2017 levels), is non-binding.

According to the NCAP tracker, cities aiming to reduce their pollution levels have either “marginally improved” or increased in pollution levels. None of the cities — called “non-attainment” cities — has achieved the national annual acceptable pollution limit of 40 micrograms per cubic metre for PM2.5 and 60 micrograms per cubic metre for PM10.

Last year, the World Health Organization revised its air pollution norms (PM 2.5) from 10 micrograms per cubic metre [annual average] to 5 micrograms per cubic metre, in order to “provide clear evidence of the damage air pollution inflicts on human health, at even lower concentrations than previously understood”.

Pollution levels in the Indo-Gangetic plain are 21 times higher than the WHO limit, according to the index. If air pollution levels are brought down to meet the WHO’s revised standards, average life expectancy can go up by 10.1 years in Delhi, 7.9 years in Bihar, and 8.9 years in Uttar Pradesh, the index says.

A 2019 study by Lancet found that air pollution was responsible for over 16 lakh deaths — about 17.8 per cent — in the country.

“By updating the AQLI with the new WHO guideline based on the latest science, we have a better grasp on the true cost we are paying to breathe polluted air,” AQLI Director Christa Hasenkopf said in a statement, adding: “Now that our understanding of pollution’s impact on human health has improved, there is a stronger case for governments to prioritise it as an urgent policy issue.”

Also read: India’s poor face disproportionately higher risk of dying from air pollution than the rich — study

Exacting a high cost in India

India’s performance on the index, which is published annually, doesn’t seem to have improved since last year.

According to the index, India’s pollution levels can be attributed to “industrialisation, economic development, and population growth”, apart from a four-fold rise in road vehicles since the early 2000s.

Using the WHO’s revised air pollution norms, the worst-affected regions are Delhi, Bihar, and Uttar Pradesh.

“However, particulate pollution is no longer just a feature of the Indo-Gangetic plains. High levels of air pollution have expanded geographically over the last two decades. For example, in the Indian states of Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, home to 200 million people, pollution has risen by 68.4 per cent and 77.2 per cent, respectively, since the year 2000.

“Here, the average person is now losing an additional 1.5 to 2.2 years of life expectancy, relative to the life expectancy implications of pollution levels in 2000,” says the index.

Globally, the index adds, air pollution is costing the average person 2.2 years of life — more than the risk of smoking (1.9 years), alcohol use (8 months), unsafe water and sanitation (7 months), HIV/AIDS (4 months), malaria (3 months), and conflict and terrorism (9 days).

The pandemic-induced lockdowns across the world had little effect on global pollution levels, the AQLI notes.

“The quality of air that citizens breathe reflects how their country understands the risks and prioritises the health of its people. The AQLI demonstrates the opportunity countries have to improve the health and lengthen the lives of their citizens if they are willing to accept the costs of environmental regulations,” says the index.

Although global pollution levels remained high in 2020, average global pollution levels have declined since 2013 “entirely due to China”, which implemented a stringent policy to tackle air pollution in the nation, the index adds.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also read: Smog of democracy — Why air pollution is not a political issue