New Delhi: A new study by a Germany-based think-tank has found that over half of China’s lending to developing countries is “hidden”, a situation particularly problematic for vulnerable economies, which may be falling into ‘debt traps’.

Now the world’s largest official creditor, with loans totalling over $700 billion, China is more than twice as big as the IMF and the World Bank combined. (The largest overall creditor is still the US, which loans to almost every country in the world.)

China does not report on its overseas lending and the People’s Bank of China does not publish its sovereign bond purchases or portfolio composition. Credit rating agencies such as Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s do not monitor official lending, which makes up the majority of Chinese overseas lending and investment.

These lapses in data have led to a poor understanding of China’s expanding global financial role and the impacts on debtor countries.

As China seeks to invest heavily overseas as part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), understanding China’s lending will give insights into its broader geopolitical ambitions.

What is BRI — the Belt and Road Initiative?

According to the Kiel Institute for the World Economy study, China has always been an ‘active international lender’, lending substantial amounts to Communist states as far back as the 1950s and ’60s. However, owing to a substantial increase in its GDP and the implementation of its “Going Global Strategy” in 1999 to foster investment abroad, China has been lending at much higher rates in the past 20 years.

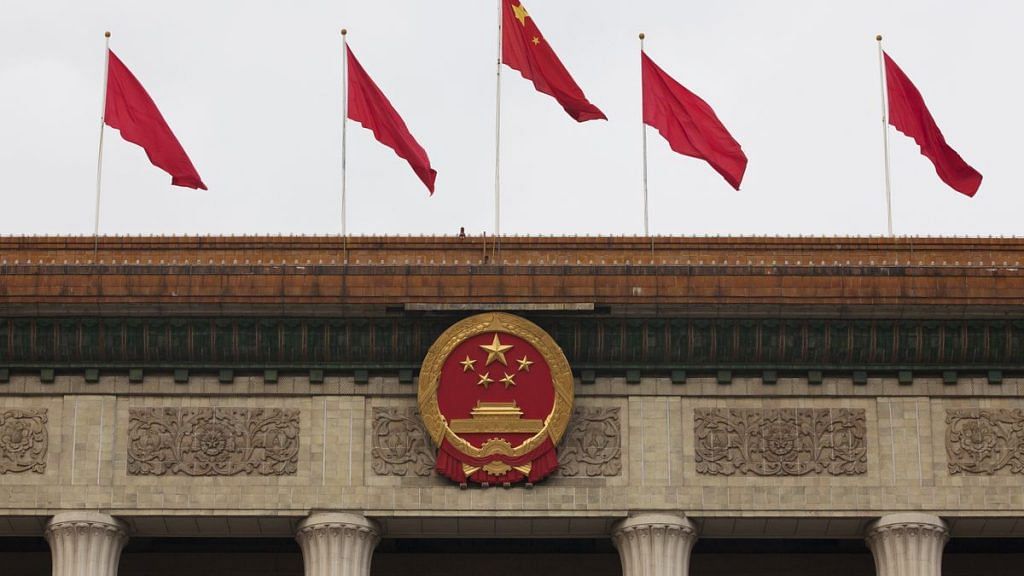

In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced the BRI — a series of ambitious infrastructure and development projects designed to connect Asia to Europe and Africa via the old Silk Road and new maritime shipping and transportation routes. Construction projects so far have included ports, roads, airports, power plants, and telecommunications networks.

The initiative aims to increase trade, improve regional connectivity and reduce poverty, and is expected to cost over $1 trillion in investments. So far, projects have been started in over 70 countries.

Also read: The world shouldn’t help save China’s Belt & Road

The lending process

Lending, whether as part of the BRI or otherwise, typically occurs between state-owned entities in China and recipient countries. The IMF found that fewer than one in ten low-income developing countries (LIDCs) report debts of public corporations external to the government, meaning that many debtor countries do not know how much money they have borrowed and under which conditions.

The study said that China often requires Chinese contractors to be used to implement construction contracts. For “risky” debtors, China uses a “circular” lending strategy. Instead of transferring money to the debtor, China pays the loans directly to the Chinese contractors to ensure that the money stays within the Chinese financial system.

This process reduces the chances that the loans will fund debtor country corruption, however, it does not eliminate corruption by any measure.

Debt traps explained

Official creditors typically lend to LIDCs at concessionary terms, with long maturities and below-market interest rates. In comparison, China lends to LIDCs at market terms with risk premia, shorter maturities, and attached collateral, found the study.

Lending at unsustainable rates leads developing countries to default, allowing China to seize the collateral. Collateral takes the form of strategic assets, such as ports, or through commodity export proceeds, such as oil. The authors note that they are unaware of other official creditors securing loans this way.

LIDCs are the most vulnerable to Chinese “debt traps”, owing more to China than to all other creditor governments and institutions combined. Many of these countries are commodity exporters and several are former highly-indebted poor countries (HIPCs) that received debt relief or cancellation in the 1990s.

Djibouti currently has the highest public debt at 104 per cent of its GDP, as estimated by the IMF, followed by Tonga and the Maldives. The most affected regions are Far East and Central Asia, particularly countries that border China, such as Laos and Kyrgyzstan.

Following LIDCs are oil-exporting countries, BRI countries, and emerging market economies (EMEs). The disparity between BRI countries’ debt is vast, reflecting that countries that have been a part of the BRI for longer have had more opportunities to borrow and have accumulated more debt over time, the study said.

Corruption is slowing down China’s expansionism

The World Bank concluded in 2018 that the BRI has huge potential to improve trade and quality of life for citizens in participating countries, but only if China works with host countries to improve debt sustainability, increase transparency, reduce corruption, and mitigate environmental, social, and corruption risks.

Loans from the IMF and the World Bank require that construction projects meet minimum human rights and environmental standards, and may come with oversight aimed at minimising waste from corruption. China has been able to lend to LIDCs at higher interest rates because its loans do not come with strings attached.

In 2017, Sri Lanka was forced to hand over the strategic port of Hambantota to China for 99 years after it could not afford high interest rates and mounting debt. Other countries, including India, had refused to finance the project because it was an “economic dud”. Public concerns about China’s use of the port as a military base have been exacerbated by its military expansionism in the South China Sea.

Pakistan may soon be facing similar problems over the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which stretches from western China to the Indian Ocean and provides China with a key shipping route for oil. Corruption has pushed the price of the project up from $46 billion in 2014 to $62 billion today, making Pakistan further indebted to China. Earlier this month, Pakistan was forced to take out a $6 billion loan from the IMF, which will not cover the rising costs of the project.

Critics argue that China is deliberately lending at unsustainable rates to ensure they can collect valuable collateral and strategic assets.

However, Deborah Brautigam at Johns Hopkins University looked at 3,000 projects financed by China overseas and found that Hambantota was the only example of a similar asset being seized to cover a Chinese debt.

Still, some African countries are worried about the debt trap and have halted similar projects with the 99-year collateral lease clause. Tanzania withdrew from a $10 billion port deal and enacted a country-wide ban on port construction earlier this year, while Sierra Leone halted plans for an international airport last year for fear of falling into the debt trap.

China is also worried about the billions lost in funding to corruption and may be looking at changing its lending terms.

In May, Chinese officials questioned Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta about corruption and costs on their construction projects. Kenya’s public debt has nearly tripled since Kenyatta came to power in 2013, and China might be blamed if Kenya defaults after being loaned billions.

After being questioned, one of Kenyatta’s aides said it was “like talking to the World Bank”.

Faced with billions of losses over corruption and aggrandised projects, China may look at changing its terms to require transparency and anti-corruption measures. Further, if more countries are forced to default, China may face international pressure to increase transparency of its lending practices and secure measures for debt sustainability in LIDCs.

Increased transparency would make it easier for international institutions to monitor China’s lending and impose sanctions over unsustainable lending practices, which could help prevent a repeat of the economic depression in the 1980s that led several countries to default on their sovereign debts.

Also read: China’s Xi Jinping defends Belt & Road, vows zero tolerance of corruption