In this excerpt from her book, Ornit Shani explains how electoral democracy in India, shaped by the imagination of bureaucrats, came to life through universal adult franchise.

From November 1947 India embarked on the preparation of the first draft electoral roll on the basis of universal adult franchise. A handful of bureaucrats at the Secretariat of the Constituent Assembly initiated the undertaking. They did so in the midst of the partition of India and Pakistan that was tearing the territory and the people apart, and while 552 sovereign princely states had yet to be integrated into India. Turning all adult Indians into voters over the next two years against many odds, and before they became citizens with the commencement of the constitution, required an immense power of imagination. Doing so was India’s stark act of decolonisation. This was no legacy of colonial rule: Indians imagined the universal franchise for themselves, acted on this imaginary, and made it their political reality. By late 1949 India pushed through the frontiers of the world’s democratic imagination, and gave birth to its largest democracy. This book explores the greatest experiment in democratic human history.

India’s founding leaders were determined to create a democratic state when the country became independent in 1947. But becoming and remaining a democracy was by no means inevitable in the face of the mass killings and the displacement of millions of people unleashed by the subcontinent’s partition on 15 August 1947. Partition led to a mass displacement of an estimated 18 million people, and the killing of approximately one million people. Moreover, creation of a democracy had to be achieved in the face of myriad social divisions, widespread poverty, and low literacy levels, factors that have long been thought by scholars of democracy to be at odds with the supposedly requisite conditions for successful democratic nationhood.

How, against the context of partition, did democracy capture the political imagination of the diverse peoples of India, eliciting from them both a sense of ‘Indianness’ and a commitment to democratic nationhood? And how, in this process, did Indian democracy come to be entrenched? It was through the implementation of the universal franchise, I suggest, that electoral democracy came to life in India.

The adoption of universal adult suffrage, which was agreed on at the beginning of the constitutional debates in April 1947, was a significant departure from colonial practice. Electoral institutions existed before independence. But these institutions were largely a means of coopting ruling elites and strengthening the colonial state. The legal structures for elections under colonial rule stipulated the right of an individual to be an elector, and the provisions for inclusion on the electoral rolls were made on that basis. But the representation was based on ‘weightage’ and separate electorates, wherein seats were allotted along religious, community and professional lines, and on a very limited franchise. Rather than defining voters exclusively as individuals, the law defined them as members of communities and groups. Thus, not only did the experience and legacy of elections under colonialism offer restricted representation without democracy, the electoral practices, which informed patterns of political mobilisation, resulted in the deepening of sectarian nationalism and impeded unity. British officials unfailingly argued that universal franchise was a bad fit for the people of India. The small and divided electorate was based mainly on property, as well as education and gender qualifications. Under the last colonial legal framework for India, the 1935 Government of India Act, suffrage was extended to a little more than 30 million people, about one- fifth of the adult population.

The national movement had been committed to universal adult suffrage since the Nehru Report of 1928. Anti- colonial mass nationalism after the First World War further strengthened that vision. But there remained a large gap to bridge in turning this aspiration into a reality, both institutionally and in terms of the notions of belonging that electoral democracy based on universal franchise would require. Throughout the first half of the 1930s in the course of making inquiries ‘into the general problem of extending the franchise’ in the run- up to the 1935 Act, both colonial administrators and Indian representatives in the provincial legislatures across the country claimed that ‘assuming adult suffrage’ would be ‘impracticable at present’, as well as ‘administratively unmanageable’.

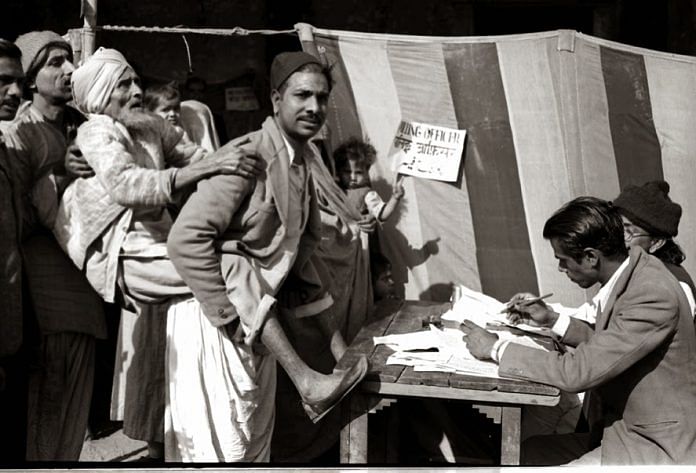

The preparation of the electoral roll on the basis of universal franchise was a bold operation, wherein the newly born state set out to engage with all its adult citizens, ultimately expanding the electorate more than five fold to over 173 million people, 49 per cent of the country’s population. Putting adult suffrage into practice and planning for the enrolment of over 173 million people, about 85 per cent of whom had never voted for their political representatives in a legislative assembly and a vast majority of whom were poor and illiterate, was a staggering bureaucratic undertaking.

The first elections took place between 25 October 1951 and 21 February 1952. But the overwhelming and complex preparatory work for the elections, in particular the preparation of the first draft electoral roll on the basis of adult franchise, had begun in September 1947. Before that ‘stupendous’ administrative task was handed over in March 1950 to the first Chief Election Commissioner of India, it was designed and managed by a small, newly formed interim bureaucratic body of the state in the making: the Constituent Assembly Secretariat (hereafter CAS), under the close guidance of the Constitutional Adviser, B. N. Rau.

This book explores the making of the universal franchise in India between 1947 and 1950. It tells the story of the making of the Indian electorate through the preparation of the first draft electoral roll for the first elections under universal franchise. This work was done in anticipation of the Indian constitution. The book, therefore, focuses on the practical – rather than ideological – steps through which the nation and its democracy were built. In this process, during the extraordinary period of transition from colonial rule to independence, bureaucrats inserted the people (demos) into the administrative structure that would enable their state rule (kratia). This process of democratic state building transformed the meaning of social existence in India and became fundamental to the evolution of Indian democratic politics over the next decades.

In the process of making the universal franchise, people of modest means were a driving force in institutionalising democratic citizenship as they struggled for their voting rights and debated it with bureaucrats at various levels. I argue that in India the institutionalisation of electoral democracy preceded in significant ways the constitutional deliberative process, and that ordinary people had a significant role in establishing democracy in India at its inception. By the time the constitution came into force in January 1950, the abstract notion of the universal franchise and the principles and practices of electoral democracy were already grounded.

The first draft electoral roll on the basis of universal franchise was ready just before the enactment of the constitution. Indians became voters before they were citizens. This process produced engagement with shared democratic experiences that Indians became attached to and started to own. The institutionalisation of procedural equality for the purpose of authorising a government in as deeply a hierarchical and unequal society as India, ahead of the enactment of the constitution turned the idea of India’s democracy into a meaningful and credible story for its people.

There is an ambiguity about the use and meaning of the term democracy. It both designates and describes empirical institutional structures, as well as a set of ideals about the power of the people by the people, and the will of the people. While analytically distinct, in practice the institutional and normative components always coexist. The thrust of this book lies in the structural makeup of democratic rule. It explores how Indian bureaucrats departed from colonial administrative habits and procedures of voter registration to make the universal franchise a reality. In some ways, they were taking their cue from pre- independence local Indian constitutional convictions about franchise such as the position of the Nehru Report, which stated that ‘[a] ny artificial restriction on the right to vote in a democratic constitution is an unwarranted restriction on democracy itself ’ and that the colonial notion of ‘keeping the number of votes within reasonable bound’ for practical difficulty ‘howsoever great has to be faced’. To do so, in the circumstances of independence, Indian bureaucrats used imaginative power with which they ultimately shaped their own democracy.

This book explains the relations between two key democratic statebuilding processes – constitutional and institutional – that took place against the backdrop of partition over the two and a half seam line years of India’s transition from dominionhood to becoming a republic. The first was the process of constitution making, during which the ideals of electoral democracy and the conceptions of the relations between the state and its would- be citizens evolved. ‘Who is an Indian?’ was a contested issue and a constitutional challenge at independence.

The second process, which took place on the ground, was the preparation from November 1947 of the preliminary electoral roll. The preparation of the roll dealt in the most concrete way with the question of ‘Who is an Indian?’, since a prospective voter had to be a citizen. The preparation of the preliminary roll for the first elections was principally based on the anticipatory citizenship provisions in the draft constitution. The enrolment throughout the country, in anticipation of the constitution engendered, in turn, struggles over citizenship. This process provided the opportunity for people and mid to lower level public officials to engage with democratic institution building and to contest the various exclusivist trends to be found at the margins of the Constituent Assembly debates.

The quality of the engagement and the responses to these contestations, the suggestions and questions that arose in the process of making the roll, and the language that these interactions produced, democratised the political imagination. It was these contestations over membership in the nation through the pursuit of a ‘place on the roll’, I argue, that grounded the conceptions and principles of democratic citizenship that were produced in the process of constitution making from above. For some key articles these contestations and the experience of roll making even shaped the constitution from below. Moreover, as a consequence of the process of implementing a universal franchise and the consequent citizenship making, the government at the centre was able to assert legitimate authority relatively smoothly over the changing political and territorial landscape of the subcontinent, giving meaning to the new federal structure.

The preparation of a joint electoral roll on the basis of universal franchise in anticipation of the constitution played a key role in making the Indian union. It contributed to forging a sense of national unity and national feeling, turned the notion of people’s belonging to something tangible. They became the focus of the new state’s leap of faith, in which they now had a stake.

Excerpt from ‘How India Became Democratic’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

Ravish Kumar is terrorist he get black money from Pakistan. He should be prisoned as early as possible……

Government is urs who stopped u.. . Raising voice against discrimination is not Anti National. Why can’t u question to those persons who cut cake and have beef biryani secretly in Pakistan?