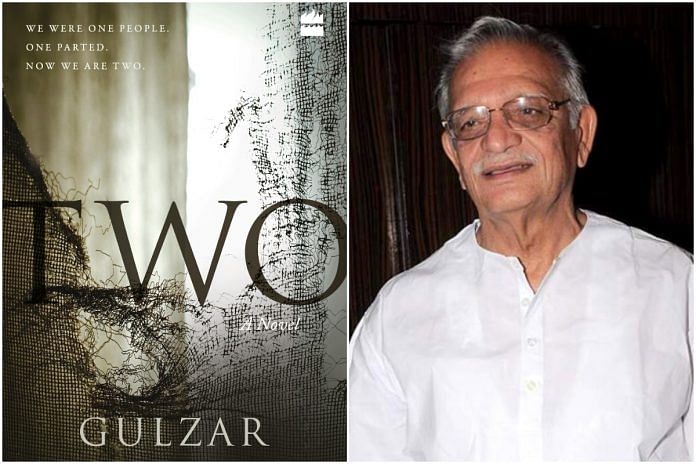

In Two, Gulzar carves the facts of the Partition to its bare bones in a masterpiece of stoic prose.

“I am still not at ease with this,” says Gulzar in the introduction to his first novel, Two. He is anxious about the various motions the original Urdu version of his text went through, passing over the desks of two other translators before ending up under his own pen.

Yet, there is something more to Gulzar’s unease than the imperfection of metamorphosing one language into another and finding that the shape of his English does not speak the same way his Urdu did. It is knowing that he can never be purged of everything he needs to say about the Partition. This is why he in his several decades long career, along with writers like Bhisham Sahni and Manto, has always returned to the telling and retelling of the disruptive violence of 1947 and beyond.

Purging the body by telling stories is an idea that has remained with Gulzar through the years. In an interview with Sukrita Paul Kumar, he recalls decomposing bodies strewn across the roads in the brutality of division, often melted into the tarmac. That is where his urge to tell it how it was underneath the fog of war comes from. “Jam gaya tha mere andar,” he says, and when the frozen unspeakable melts out slowly, the end of the line is a novel like Two which carves the fact of the Partition down to its bare bones.

Gulzar’s short novel starts in the town of Campbellpur in 1946, with a cast of characters who never fully know what is going on and how their life will change if and when the Partition takes place. Fauji the truckdriver, Lakhbeera the dhaba-owner, Master Fazal and Karam Singh who are schoolteachers and close friends, sisters Soni and Moni, and several others come together while going their separate ways on an over-encumbered truck to India.

The road, riddled with flashes of death, throws everyone on the truck to different places, to refugee camps, abandoned on the way, running businesses in Europe, living like a graveyard-hermit, or underneath a grave. The swiftly-paced story flows across time and into parts of Indian history where the remembrance of the Partition would likely have been strongest – most prominently the 1984 Sikh Riots.

Gulzar’s language for the first time goes beyond the heaviness of his short prose and the loss felt in his poetry. Like sheets being pulled off of old furniture, his novelistic writing in a strange new way brings him closer than ever to the Partition as it happened, gouged out from the surface of its stories and its mythos.

His short stories, for instance, often blow the dust off the contradictions inherent in the senselessness of violence. In “Dhuan,” he tells the story of a woman whose dead husband in his will expresses a wish for cremation instead of a traditional Muslim burial. The husband’s body ends up stolen for burial while his wife, the Chaudhrain, is murdered and her body set alight. Gulzar ends with an invocation to the oddness of it all: “Zinda jala diye gaye the; aur murde dafn ho chuke the,” noting that in the fog of violence one somehow does not even mind fighting to the death over the dead.

His poetry too revels in the oddity of a violence with no sensible roots except, perhaps, fear. This is why in one of his pieces, he repeatedly invokes the infamous maddening lament of the protagonist from Manto’s “Toba Tek Singh”: “Mujhe wagah pe toba tek singh wala bishan aksar yehi keh ke bolata hai / upar di gur gur di moong daal di laltein di hinustan te pakistan di durr phitey munh.” One way or the other, it is the sorrow of response that Gulzar has always managed to capture so well.

In Two, he changes. He refuses to linger on the pain of death, and every short sentence pushes the novel away from the time it could have taken to contemplate – exactly like those who were stricken by the Partition and surrounded by its rubble. They had no means to stay and mourn before they had to keep walking on to borders they could not even locate. Gulzar’s articulation of sorrow changes in Two. “Fauji sobbed,” he writes, “beat his head and started hurling abuses in desperation. God knows who he abused and to what end. One by one, everyone stepped off the truck.” We can’t listen to the howls and croons of loss anymore as we could with his poetry. Language stopped dead in its tracks is what makes Gulzar’s first novel one of the finest works in his oeuvre. It is its silences that linger even as its words cannot.

Shantam Goyal is a Writing Tutor at Ashoka University, while also doing his M.Phil from the Department of English, University of Delhi.