Only 8.52% of Rs 20,000-cr budget has been released in 3 years by Modi govt to clean Ganga; inter-ministerial tussle, lack of cooperation from states major hurdles.

New Delhi: Cleaning the Ganga was one of the main electoral promises of the BJP before the 2014 Lok Sabha elections. And one of the most challenging tasks taken up by the Narendra Modi government after coming to power.

More than three years on, however, the task has remained as daunting as the mighty river, the multiple strategies, programmes, announcements and good intentions notwithstanding.

So much so that the National Green Tribunal (NGT) had in February 2017 observed that “not a single drop of Ganga has been cleaned so far”.

Prime Minister Modi’s last cabinet reshuffle in September put Nitin Gadkari in charge of the ministry of water resources and Ganga rejuvenation, replacing Uma Bharti who was seen to have failed to deliver.

ThePrint takes stock of why India’s longest and most ‘sacred’ river continues to be as filthy as it was three years ago.

Namami Gange

Namami Gange, a three-phase cleaning plan, was initiated under the National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) in June 2014 with a massive budget of Rs 20,000 crore. It promised a cleaner Ganga in just five years.

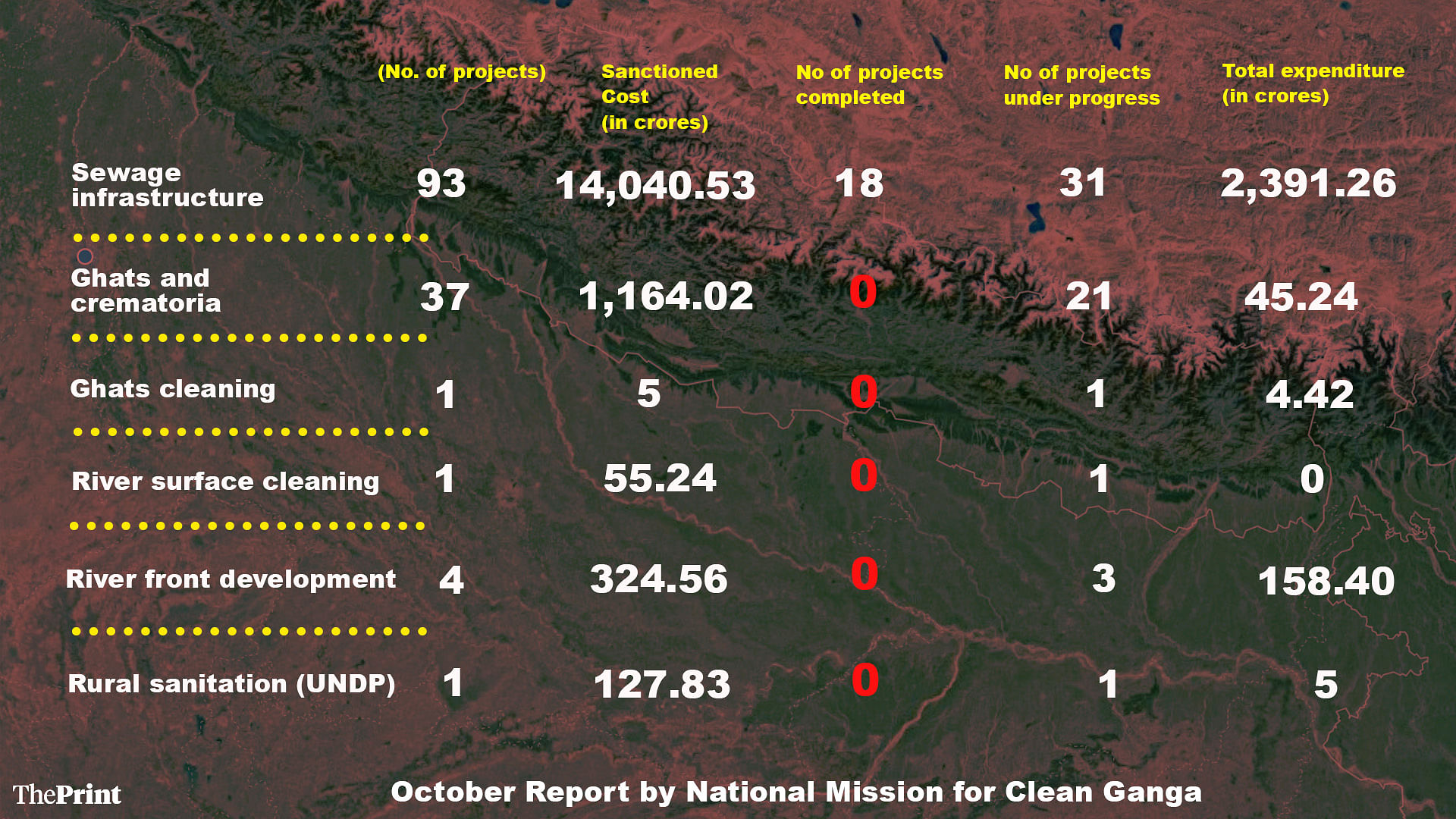

Over three quarters of all waste from the northern plains still flow into the Ganga untreated, owing to the gap between treatment capacity and waste generated. A total of 163 projects have been sanctioned at a cost of Rs 12,892.33 crore under the Namami Gange programme till June 2017, according to the ministry of water resources.

However, only Rs 1,704.91 crore has been released until June, or barely 8.52 per cent of the Rs 20,000-crore budget.

The Modi government has also drawn flak for dropping some key initiatives taken by past governments from its priority list.

De-emphasising ‘Aviral Dhara’

The Manmohan Singh government in 2009 had created the National Ganga River Basin Authority. Not only did it target the entire river basin, it also created a crucial distinction between ‘aviral dhara’ and ‘nirmal dhara’.

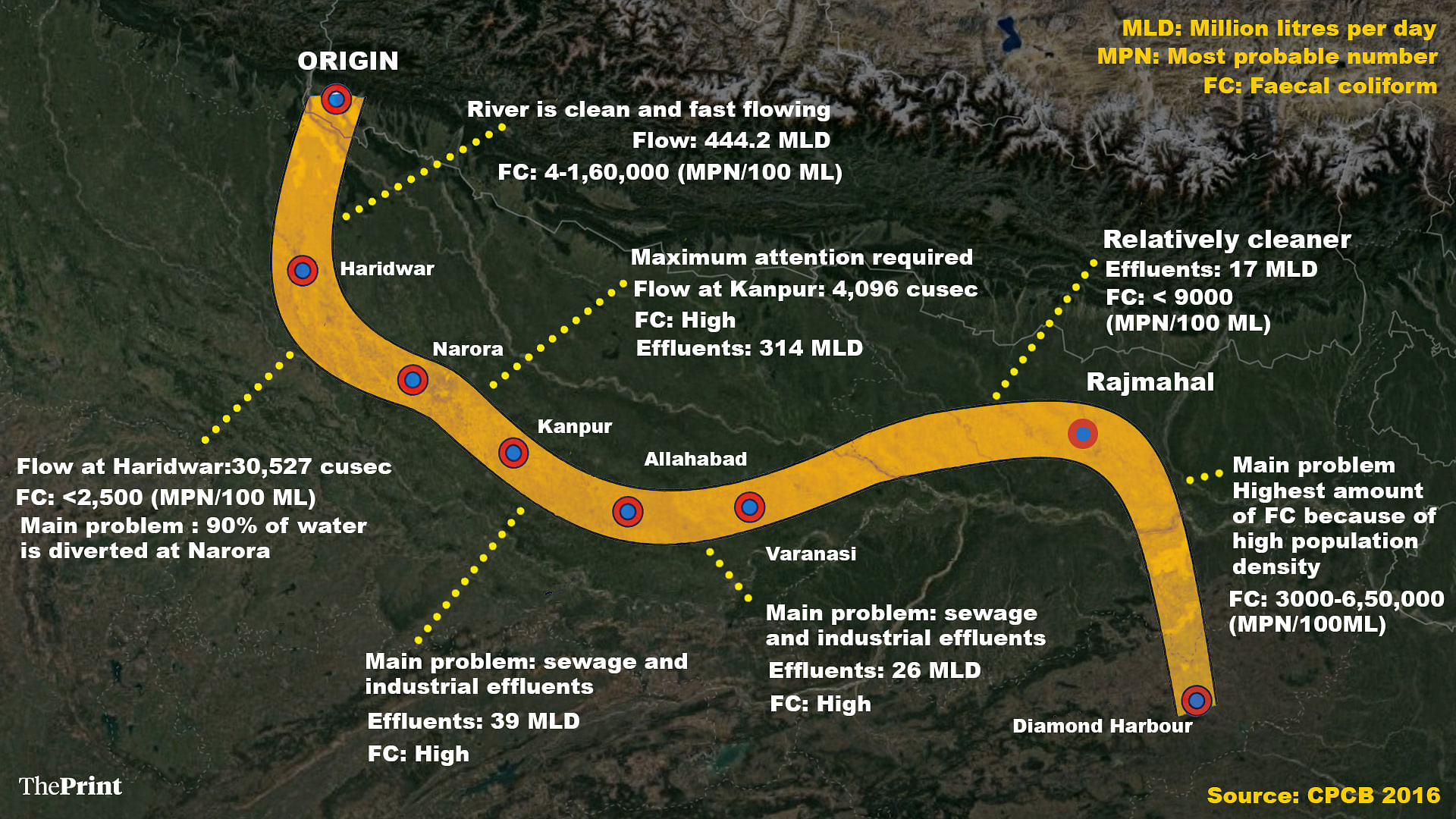

‘Aviral Dhara’ denotes continuous flow which ensures self-purification by the river as it moves down the plains. While, ‘nirmal dhara’ means a clean flow. Both are vital to the morphology of the river.

NGRBA planned to reduce diversion of water for other purposes, limit the construction of dams and hydel-power infrastructure along the river, so that the natural flow of the river is not compromised.

However, under both the previous and the current government, the river’s decreasing volume and diversions to industries and irrigation have created grave problems, especially in the context of hydropower projects on the Ganga and its tributaries.

After the 2013 Uttarakhand floods, committees were set up to review the contribution of hydel plants to the tragedy. The panels recommended striking down 23 projects and restricting such projects in the upper Ganga.

An affidavit submitted by the environment ministry to the Supreme Court in December 2014 acknowledged the role of hydropower plants in the floods and the destruction of the Ganga’s ecosystem.

“Any decision on hydropower projects should be on very strong and sound footing with scientific backup. To maintain aviral dhara in the form of environmental flow is sacrosanct,” the affidavit read.

The environment ministry, however, has since reversed the decision, allowing construction of five hydel projects. This resulted in a tussle between ministries, with the water ministry strongly opposing these plants.

“Concept of aviralta has taken a backseat. They have proposed 250-400 hydropower projects,” said Mallika Bhanot, a member of Ganga Ahvaan, a citizens’ forum.

Lack of cooperation from states

Although funds come from the Centre, the implementation lies with the states in the river basin, which tend to create hurdles, officials and experts say. State PCBs, nagar nigams and private bodies all share responsibilities when it comes to cleaning the Ganga, leading to a lack of coordination, multiplicity of proposals and slow progress, they say.

The tendering process and bureaucratic red tape have stalled progress, they add.

“We didn’t get adequate support from the government,” said Shashi Shekhar, former secretary, ministry of water resources. “Bihar and West Bengal were always on board; Jharkhand was also not against us. There was some confusion with UP and it is a major chunk because after that the river has enough water to clean itself.”

State pollution control boards

It is alleged that corruption is rampant in state PCBs, leading to lax implementation of rules.

Gaurav K. Bansal, an advocate with the NGT, said, “I have noticed that Central Pollution Control Board’s directions are not followed by state PCBs and they have no will power to work.’’

Most reports, he claimed, were prepared either without field visits or through consultants. A former CPCB official backed this argument, saying most of their figures were not accurate.

Ganga Action Plan

The first attempt to clean the river was made in 1986 when the Rajiv Gandhi government launched the Ganga Action Plan or GAP-I, aimed at restoring water quality to the ‘bathing class standard’ by treating sewage and industrial pollutants.

GAP-II was launched in 1993 with a broader strategy since large amounts of pollutants were flowing into the Ganga through its tributaries such as Gomti, Damodar and Yamuna.

While GAP-I and GAP-II spent Rs 986.34 crore until March 2014, there are many reasons why GAP-I and II failed. Among them is the poor upkeep of sewage treatment plants (STPs).

Sewage treatment plants (STPs)

STPs were not only few in number but also performed poorly. They were inept in treating microbes, such as faecal coliform, and other chemical pollutants. Besides, maintenance of STPs was severely hit due to a lack of funds.

“STPs were not operational; the locations were wrong and municipalities were not maintaining them properly or paying the power costs,” Jairam Ramesh said.

Shashi Shekhar believes it is the lack of accountability that caused this problem. “In other countries, STPs last for 30-40 years without any problem. In India, they become ineffective in 7-8 years.”

Nayan Sharma, river science expert and a professor at IIT Roorkee, explained that at present both industrial waste and sewage are being thrown into a sewer, which goes to a centralised STP.

“An STP cannot treat industrial, chemical and toxic metal waste because it requires different techniques,” he said. This makes existing STPs highly ineffective.

Clearly, industrial pollution is something that successive governments have failed to address. “Industries are pampered sons and daughters of politicians,” said lawyer M.C. Mehta, who has been fighting for the Ganga cause for 32 years.

By the end of GAP-I, only 45 per cent of the grossly polluting industrial units had effluent treatment plants. Many didn’t function properly even as the effluents discharged reached 2,667.16 million litres per day (MLD).

Under the Modi government, till October 2017, Namami Gange had created only 224.13 MLD of sewage treatment capacity of the 2205.08 MLD capacity it aimed for. In the past three years, merely 18 sewage infrastructure projects have been completed of the 93 sanctioned.

The sluggish pace of the Namami Gange programme perhaps explains that it is no different from many of the previous initiatives.

How much longer?

According to M.C. Mehta, the Ganga has been reduced to a tool to earn votes. “No real change is expected. The target has been pushed from 2019 to 2020 because of the forthcoming Lok Sabha elections,” he said.

Gadkari had in October said he would “try his best” to deliver by 2019, but could not promise much though.

The centre can not complain of non cooperation of states having all states in the bag of the ruling party and having a strong high command. So reason lies somewhere else. It is their unwillingness to enforce the law on polluting industries as it is rightly said they are sons and daughters of politicians. Why can the gov not installed adequate STP plants and en sure their maintenance? There are excuses galore. I think choice of Gadkari was a wrong decision. U need someone who has dedication for the job.

There can be NO excuse for this non-performance, now that UP has Yogi and Nitish is an ally.