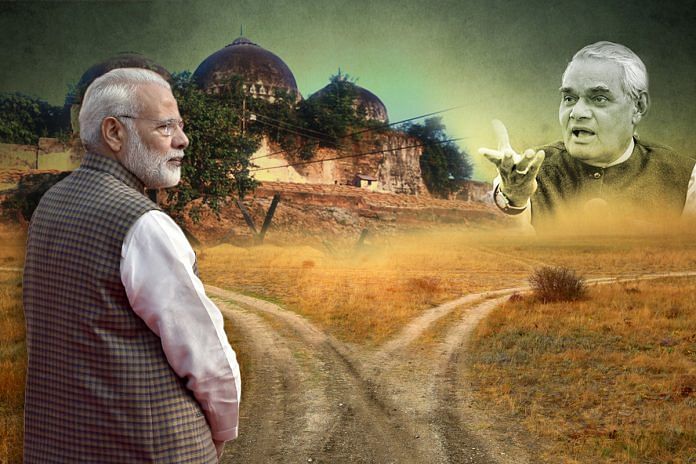

The Ayodhya issue will test Modi’s political capital, because one party will leave the table more aggrieved than the other.

As the Ram Mandir issue gets reignited, the spotlight is on how Prime Minister Narendra Modi handles this hot-button, emotive subject.

Even as the Supreme Court began hearing the appeal against the 2010 Allahabad High Court ruling Tuesday, the truth is that any order will have to eventually be implemented by the political executive. And that is bound to test the PM’s political capital, because one party will leave the table more aggrieved than the other.

This is where he may want take a leaf out of former PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s book—even though the two have very different styles of functioning.

It was late 2001 when two influential leaders of the Ram temple movement—VHP’s Ashok Singhal and the head of the Ramjanmabhoomi Nyas, Ramchandra Paramhans—mounted pressure on the then BJP-led government by demanding attention to an issue that had catapulted the party to the national political centre stage.

Vajpayee could not duck or deflect this tricky issue – especially because his deputy was L.K. Advani, who had played a lead role in the movement.

So, he assuaged the concerns of Singhal and Paramhans by setting up an Ayodhya Cell directly under the Prime Minister Office. He then got his trusted officer Ashok Saikia to identify a young bureaucrat, who had been an effective district magistrate in the Faizabad-Ayodhya jurisdiction.

The Ayodhya cell got its own infrastructure: a room in the PMO, and two-rooms in Vigyan Bhawan. The officer chosen for the job was Shatrughan Singh, who met all the stakeholders and reported to Saikia.

They came up with three possible approaches for the PM to take a call on.

First: The Hindus get to build their temple while Muslims can build a grand mosque, a few kilometres away where Babur’s commander Mir Baqi had camped. He is believed to have constructed the Babri Masjid. The catch here was to convince the Hindu groups to guarantee that they would withdraw similar claims on other disputed temple-mosque sites in Mathura and Kashi.

Second: Divide the disputed territory into two halves, and draft an agreement for religious practices to take place without any clashes.

Third: The Hindus build a temple a short distance away from the disputed structure near what was called ‘Arah ghar’ – a site that the state government had already acquired.

These were meant to be the possible lines of negotiating a solution. The All India Muslim Personal Law Board, the Babri Masjid Action Committee and other Sunni organisations had shown little confidence in the initiative. Some informal talks were conducted with the late Hashim Ansari, one of the oldest litigants in the matter.

The PMO staff made a detailed presentation to Vajpayee sometime in February 2002, about three months after the Ayodhya Cell was formed. The presentation laid out all the scenarios with impressive drawings and calculations.

Vajpayee did not utter a word through the presentation. And then in his trademark cryptic style said: “Aap log chhaatr bahut achchein hain (You all are good students).” And then he left the meeting.

No instructions followed. The report never saw the light of day again. The Ayodhya Cell gradually faded away. Its officers were absorbed in the Cabinet Secretariat, although it remained very much on paper and in Vigyan Bhawan. No one even knows if official orders were issued to close it down by the Manmohan Singh government.

What is important is that the issue never resurfaced, except when the VHP wanted to do the shilanyas at the site. This was within months of that presentation. Saikia summoned Singh, who then rushed to Paramhans with a plea that the shilanyas be done in his ashram and not at the disputed site. This solution was found acceptable and a brewing crisis averted.

Much time has since passed. Singhal, Paramhans and Hashmi are no longer alive. Others have aged. And yet, there are people who are now breathing life back into the issue.

It doesn’t matter which way the court goes, what will matter is the position the Modi government takes. Will it allow the flames to be reignited for political reasons or will it find a more sagacious way out to ensure communal passions are not stoked?

The PM has this option because someone like Vajpayee acted with political tact at a time when wounds were raw and the pressure on the first BJP PM to build the temple was at its peak.

The call the Modi government takes, starting with its approach in the Supreme Court, will be among the most significant ones in his term. One thing is clear. From here on, it will be a political call at every stage, including the decision to hide behind legal cover.