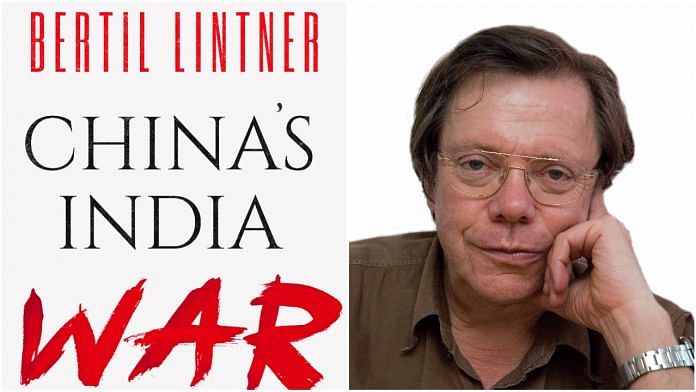

In 1970, journalist Neville Maxwell’s book titled ‘India’s China War’ painted India the provocateur of the 1962 India-China war. Decades later, a book by journalist Bertil Lintner titled ‘China’s India War’ challenges that long-standing narrative and says the attack by China was unprovoked and unexpected.

Excerpt

It was entirely unexpected that the Chinese would attack. The Indians had observed a massive build-up across the border and there had been several encounters between the Indian Army and the Chinese PLA in the days before the main attack, including bombardment of Dhola and Khenzemane on 19 October 1962. But the ferocity and the sheer co-ordination of the Chinese attacks on 20 October 1962 and the days that followed stunned the Indian security establishment as well as international observers. At daybreak on that day, artillery guns and mortars began intense bombardments across the Thagla Ridge.

According to Brigadier John Dalvi,

At exactly 5 on the morning of 20th October 1962, the Chinese Opposite Bridge III fired two Verey lights. This signal was followed by a cannonade of over 150 guns and heavy mortars, exposed on the forward slopes of Thagla…this was a moment of truth. Thagla Ridge was no longer, at that moment, a piece of ground. It was the crucible to test, weigh and purify India’s foreign defence policies.

Dalvi called it ‘The Day of Reckoning—20th October 1962’. The all-out assault on Indian positions north of Tawang was on.

On the western front in Aksai Chin, the fighting was spread out over a swathe of land from north to south, covering a distance of approximately 600 kilometres. But the thrust of the Chinese towards the south was confined to a relatively narrow area, which measured approximately 20 kilometres from west to east. Most of the attacks by the PLA seemed to be confined to dislodging Indian troops from the outposts that had been established as a result of the government’s Forward Policy rather than for capturing territory. According to Indian military analysts, ‘In the Western sector, [the] Chinese had a limited aim. They were already in occupation of most of the Aksai Chin plateau through which they had constructed the Western Highway connecting Tibet and Xinjiang. In this war, their aim was to remove the Indian posts which they perceived were across their 1960 Claim Line.’ They had no intention to move forward deep into Indian territory, as they did in NEFA.

The Aksai Chin plateau was and still is virtually unpopulated; this had made it possible for the Chinese to build their highway there in the mid-1950s without the Indians finding out about it until a year after it had been completed. The name Aksai Chin means ‘the desert of white stones’, and the altitude varies between 4,300 and 6,900 metres above sea level.

In the past, some Ladakhi villagers used the area for summer grazing and made it part of the Cashmere wool trade, but otherwise there has been no commercial activity worth mentioning in the area. Whatever ancient trade routes that existed were secondary, and the only valley, if it may be called such, is along the River Chip Chap that flows from Xinjiang to Jammu and Kashmir. During the 1962 War, the Chinese captured several Indian positions in the valley and have since controlled most of the area.

During the weeks of fighting in this western sector of the theatre of the 1962 War, it became obvious that the Chinese knew exactly where the Indians were, how many there were at each position, and what kind of weaponry they had. As was the case in the NEFA in the east, pre-war intelligence gathering had been carried out in the Aksai Chin area by small teams of surveyors who could move freely and, presumably, undetected on the barren plateau.

A contentious issue on the eastern front was the location of the Indian outpost at Dhola in the River Namka Chu gorge, where the borders of India, Bhutan, and Tibet intersect northwest of Tawang. The post was created on 24 February 1962 and, according to the Henderson Brooks–Bhagat Report, the site ‘was established north of the McMahon Line as shown on maps prior to October/November 1962 edition. It is believed that the old edition was given to the Chinese by our External Affairs Ministry to indicate the McMahon Line. It is also learnt that we tried to clarify the error in our maps, but the Chinese did not accept our contention.’ The Chinese, in any case, would not have paid much attention to Indian maps. Their objective was entirely different: to teach India a lesson.

This remark in the Henderson Brooks–Bhagat Report is anyway a far cry from the claim by Neville Maxwell and others that the establishment of the Dhola outpost triggered the 1962 War and that India was the aggressor. Chinese troops had crossed the Namka Chu on 8 September, surrounded an Indian outpost in the gorge, and destroyed two bridges on the river. The nearby Dhola Post was reinforced and firing from both sides continued in the area throughout September. Three Indian soldiers were wounded when the Chinese threw hand grenades at their position, but otherwise, there were no casualties.

When the final attack came on 20 October, the Indians found that the Chinese had cut all their telephone lines the night before. In preparation for the assault, the Chinese had also taken up positions on higher ground behind Indian defences and were thus able to attack downhill on the morning of the attack. After the Chinese artillery barrage from the Thagla Ridge overlooking the Namka Chu, the PLA destroyed all Indian artillery positions and surrounding fortifications. The Indian border posts as well as Dhola and Khenzemane were overrun by ground forces within hours, and their defenders either lay dead or were captured alive. The strength of the Chinese attacking force was estimated at 2,000, while the Indians at those outposts numbered only 600.

This is an excerpt from ‘China’s India War: Collision Course on the Roof of the World by Bertil Lintner.’ Excerpted with permission from Oxford University Press India.

The Henderson-Brooks Report has still not been released in full by the Indian Government after 55 years.

And regarding war preparations, most nations prepare for war at all times against their perceived enemies, see NATO. Even if China had made preparations in 1959 they didn’t attack India then but only in 1962 after Nehru’s provocative Forward Policy and several ignored warnings from the Chinese including those through diplomatic channels.

The truth is that the Indians gambled thinking the Chinese were in no shape to fight another war after the Korean one and the disaster of their Great Leap Forward. They were proved wrong.