The cyberspace is now essential to the political management of memory, whether it is dubious historical claims about the Armenian genocide, or Hindu claims about the Taj Mahal.

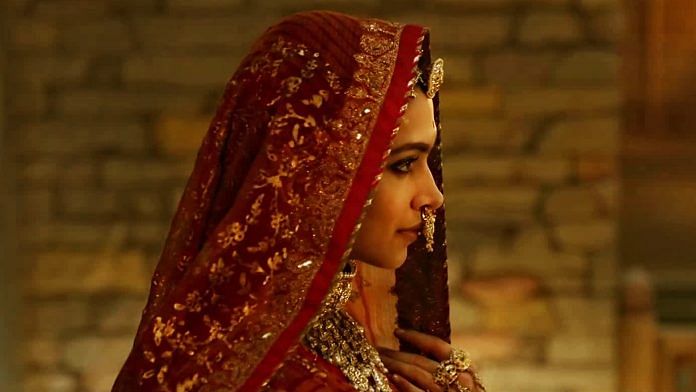

Padmavati, had she existed, would have perfectly understood the problem of fake news that bedevils the profession of journalism, public life, and the institutions of democracy in any number of countries today. She would have understood that established criteria of credibility, such as those that historians and journalists rely on, often ring less true for people than compelling, if factually dubious, narratives about identity, community, and politics.

She might have conjectured that the legend of Padmavati, born of the mind of a 16th century poet writing in Avadhi and sustained by the anti-colonial imagination, was equally a creation of the political power of spectacular media and what the scholar Henry Jenkins calls “spreadable” media.

Historian Partha Chatterjee tell us that anti-colonial nationalism was as much a cultural project as a political one. Colonised Indians did not concede cultural sovereignty to the British even as they were politically subjugated. Autonomy over the realm of culture has then been a fundamental attribute of Indian identity from colonial times onward. And the right to control the representation of the community, in public discourse, documents, and media, has been key to expressions of cultural identity.

That right is now asserted against the postcolonial state as it was earlier against its colonial predecessor. The guardians and spokespersons of community, usually self-appointed, are mostly men and, more often than not, men with a regressive politics. It is this very logic that informed Tilak’s opposition to the Age of Consent Act in 1891, which targeted child marriage, the Muslim male opposition to the Shah Bano case in the 1980s, and the recent opposition of Hindu goons to the film on Padmavati.

To this historical mix, add the pervasive reach of global televisual media. We live, as the French philosopher Guy Debord explained, in the society of the spectacle. The round-the-clock depiction of life on television is key to this condition. This fact informs every act of public violence and is part of the calculation of those who commit such acts of violence, whether the terrorists responsible for 9/11 and 26/11, mass shooters in the US, or the Hindu nationalist groups making threats to the actors and director of Padmavati.

Finally, layer with the internet. The internet has radically transformed our sense of the past, shaping what is remembered and forgotten and how it is remembered and forgotten. In no mean measure, this is thanks to companies like Google, Facebook, and Twitter which are gatekeepers to what we see online of the recent history of the world. With virality or spreadability, a story can easily snowball online into what Cass Sunstein has described as an “informational cyber-cascade”, something that takes on a truth-force of its own as it spreads.

This is why groups that are invested in a particular narrative are keen to establish a presence for their stories online. Cyberspace is now essential to the political management of memory. The problem of fake news about the recent US election on Facebook, or dubious historical claims on Wikipedia about the Armenian genocide, or Hindu claims about the Taj Mahal being a Hindu architectural structure are all manifestations of the same phenomenon.

Historical truth is a modern, post-19th century idea, now complicated – once again — by social media era.

While the idea of the ‘insult’ to Padmavati represented by Bhansali’s film germinated offline, it was no doubt compounded by the discussion of the issue online on Twitter or outrage on WhatsApp groups and the like.

The legend of Padmavati, firmly etched in cultural memory, has now taken on another spectral life online, inextricably tied to controversy. Given the power of cultural memory, the politics of community in India, and the amplificatory power of the internet, this ghost in the machine is unlikely to be vanquished.

Rohit Chopra is an associate professor at Santa Clara University. He tweets @rchops and @indiaExplained

May be she was. But consider the following-

1. That scores of women committed Jauhar after the Khilji’s siege and afterwards is documented.

2. Malik Muhammad Jaisi was the first one to tell the tale of Padmavati- the idea was the provide a human manifestation/symbol of the pain felt by all and sundry.

3. In contemporary India, even the mention of Padmavati as “in some accounts” have been removed from history books, whitewashing History and promoting amnesia.

I doubt Mr Chopra gives two hoots about all this. He is a sepoy, a bootlicker of the West who will do and say whatever pleases them- lest he finds himself out of a job…

Nice article about truth , perception and how internet shaping it.

As far as padmavati goes, only past documentation was Padmavat poem, in 15th century…it could be totally work of fiction or some facts sugar coated with grand tale of rajput valour.

No one alive to tell the facts whay happened..all folklore based on what passed to generations.

All I knew about padmini..was in Amar chitrakatha…Our history book had no mention of this event.

Rest is wikipedia…which is being daily worked ..has that parrot story in it, which is ridiculous.

Dubious claims of the Armenian genocide, the Holocaust, Khmer Rouge genocide of Cambodians, Rwandan genocide of Tutsis…I wonder why the author stops at the Armenian case. I guess, according to the author, only the negation of the Armenian genocide is “real news”.

“Historian” Partha Chatterjee That Duffer is a marxist historian …an oxymoron .. enough said

I don’t know what you mean by Armenian Genocide being fake news. Armnenian genocide is a historically accepted fact. Other than Turkey, most countries of the world officially recognize the mass killings of Armenians as genocide, as have most genocide scholars and historians.