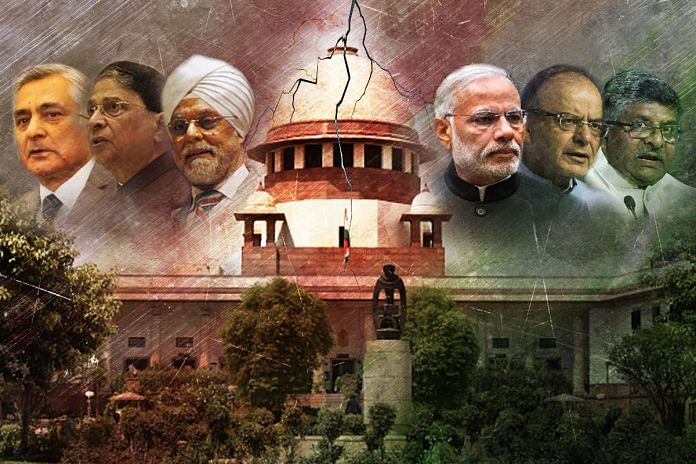

There’s much room for reform in the government-judiciary relationship. But first, both need to speak the same language.

If there was one issue on which the BJP and the Congress were ready to bury their differences even after the bitterly fought 2014 Lok Sabha elections, it was on establishing legislative superiority in the selection and appointment of judges.

The National Judicial Appointments Commission Bill was the first productive political conversation between the two parties – Congress was in a majority in the Rajya Sabha then – after the swearing-in of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. A consensus was fast emerging that the collegium system no longer inspired the requisite trust.

And just then, the government decided not to grant leader of opposition status to the Congress in the Lok Sabha because it had won less than 10 per cent of the seats. With that ended the possibility of any consensus, or as a senior parliamentarian put it: “The opportunity of Parliament to assert (itself) before the judiciary was lost.”

Since then, the Modi government’s efforts to introduce judicial reforms through persuasion have met with frustration. This is only made worse by the fact that it has failed to do so despite its handsome majority in the Lok Sabha.

The second frustration on this score is the inability to restore balance into an institutional relationship where the judiciary had come to enjoy the upper hand when relatively weak, unstable coalition governments were in power.

The Supreme Court then went on to knock off the NJAC Bill and brought forward a new Memorandum of Procedure for the collegium to appoint judges. This too has got stuck with the government insisting on a screening process to shortlist candidates for selection of judges plus a national security clause for the government to overturn a proposal.

This resulted in a stand-off where the government first held up appointments but couldn’t do so for long because litigants would get affected. The judiciary, sadly, saw this as an opportunity to go back to its old ways, adding fuel to the government’s frustration and anger.

So what’s the big picture on appointments today? There are only 679 high court judges against a sanctioned strength of 1,079. Collegiums of high courts have moved only 115 proposals against the 400 vacancies that exist. Of these, 56 are pending with the Supreme Court collegium while the rest are at different stages of government approval.

Even on the improbable assumption that all 115 will be appointed, there will still be 285 vacancies across high courts. It’s important to note that no selection-cum-appointment process can start without high court collegiums making their proposals.

And here again the rough calculation is that on an average the SC collegium turns down 30 per cent HC proposals. The law ministry then sends it back to the concerned HC for a fresh panel.

In this entire effort, the government may rightly feel that it has turned into a post office of sorts, relaying messages without any say except, perhaps, being able to say ‘no’ once to any collegium proposal for a SC judge. The government has to concur if it’s sent back.

Even in the SC, there are currently six vacancies and on 4 December, there will be nine ‘acting’ CJs in different high courts because the SC collegium is yet to send its proposal. With over 3 crore cases pending across the country, the big picture isn’t encouraging even though the government appointed a record 126 judges last year.

Now, there’s also a story on the other side. The government is the biggest litigant across Indian courts. And quite a few times, one department of the government is fighting the other. To make matters worse, government agencies tend to go through all stages of appeal, making it an even more tedious process. In fact, the SC has conveyed its concerns rather candidly on this front to the central government.

This prompted the PMO to issue orders that two wings of the government will not file petitions against each other, without first bringing the matter to the Cabinet Secretary, who is expected to make every effort to resolve it amicably.

Recently, instructions have gone out to re-examine all old laws from the perspective of reducing litigation. For instance, it emerged that nearly 60 per cent cases in the courts relate to the Motor Vehicles Act and largely to challaning or imposing a fine under Section 5 of the act. So, district police heads were given powers to dispose of them through an amendment.

Essentially, reform is needed on both sides but what’s important is to first change the grammar of the conversation among institutions.

The government needs to understand that it can’t introduce transformational changes on its own. There are only two ways to do it – either by forging a consensus with other political parties or by striking a ‘deal for change’ with the judiciary.

The first option is more or less closed with opposition parties now gearing up for the 2019 elections. The second alternative is an ongoing conversation, where the government will have to cede some space because the judiciary is better placed to weather a stalemate.

At the same time, the judiciary needs to introspect hard on its own public credibility given that there’s a mountain of data to bare its inefficiencies. Higher courts will have to prioritise basic judicial work like disposing of appeals over the temptation of indulging in increasing their territories of influence in other domains.

If not, there could arise a graver, more undesirable, situation of over-correction through legislative diktat in the future. And that certainly won’t be acceptable.

In short, what’s needed is institutional self-restraint. And while political temperatures may continue to rise, the next year or so is a good time for calm minds to get down to the quiet, serious work of repairing, and may be recasting, this relationship for better results.

The solution to Judicial Overreach and the Collegium system is to make the procedure for the removal of SC judge easier and that process lies entirely with the power of the Legislature . So while the Judiciary may appoint its own people – the Legislature must be able to FIRE them on its own should the people loose confidence in the rectitude and competence of the SC judge or Judges in question.