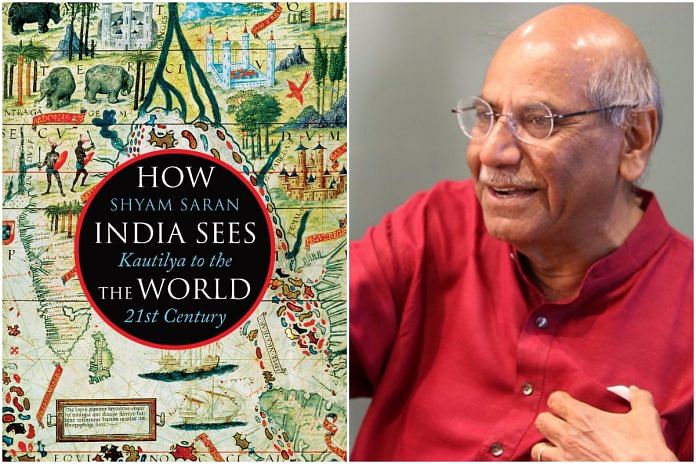

The book ‘How India Sees The World’ traces the roots of Indian quest for multipolarity in and strategic autonomy to Kautilya and Kamandaki.

Shyam Saran’s book, ‘How India Sees The World’, is a must read for diplomats, and those in the wider academic and policy community. The book provides insights into the broad consensus in the Indian diplomatic establishment on critical issues, and the collective osmosis through which succeeding generations are trained.

Tracing the roots of Indian strategic thinking to Kautilya and Kamandaki, he has shown its relevance to India’s striving for multipolarity in international relations, and “strategic autonomy” in its decision-making. This “strategic autonomy” is traced to ancient Indian statecraft, and the colonial as well as post-Independence experience in the subcontinent. He has persuasively argued that challenges in the South Asian subcontinent need to be addressed based on an approach that goes beyond the traditional and narrow confines of sovereignty and national boundaries, given the deep cultural and other interlinkages.

Based on his personal involvement, Saran has dwelt at length on the complex domestic and foreign policy dynamics that impacted the conclusion of the civil nuclear cooperation agreement with the US in 2008, and the Paris climate change agreement in 2015. In the bilateral context, he has elaborated on the evolution of some aspects of India’s relations with Pakistan, China and Nepal.

Differences, doubts and dilemmas that dogged both the US and Indian governments at that time about the longer term reliability of the new partnership, reveals the importance of leaders’ visions and endurance when an existing template is sought to be changed by overcoming “hesitations of history”.

Both President Bush and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh had to intervene personally and repeatedly to instruct their negotiators to find a creative way out when existing norms and attempts to minimize the inevitable disruption led to logjams. India’s approach was also conditioned by the memory of US reneging on its commitment to the Tarapur plant after our test in 1974. Norm-changing negotiations between two democracies brought suspicions in legislatures and predispositions in the wider policy world into play.

Following the agreement, defence cooperation, through purchases, technology partnerships, joint exercises and policy dialogues expanded. Through the framework of newly minted strategic dialogue, counter-terrorism, homeland security, renewable energy, trade and investment got renewed attention. The new relationship expanded also opportunities for India in Europe, Japan, Australia, among others. Those with an adversarial approach to India also recognized the constraints imposed on their global options.

Saran’s narration of the climate change negotiations from Copenhagen in 2009 to Paris in 2015, from “failure” to an agreed outcome, from “shared but differentiated responsibility” to peer evaluation of nationally determined contributions, is a riveting account. At the 1992 Rio conference, India’s economic reform process had just begun, China’s economy had not yet transformed itself, and the developing countries as a group had held firm, with some signs of dissension among the small island developing states.

By 2015, China had emerged as the largest current polluter, had announced a separate bilateral deal with the US for emissions, many developing countries had become part of the group of those “ambitious” for a successful outcome. Even in India, many questioned if it made sense to hold out and be blamed for failure when the underlying dynamics had changed. Saran writes that “it is within a zone of relativity that diplomacy can enable accommodation, compromise and conciliation among states”.

The chapters on bilateral relations offer insights into the border issues with China, India’s role in transition from monarchy to democracy in Nepal, and the process of the Musharraf- Vajpayee joint statement of January 2004.

I had supported, as joint secretary in the ministry, his efforts with Pakistan. The relative success of the “peace process” between 2004 and 2007 has lessons for subsequent efforts. Musharraf and Vajpayee wanted to make progress, and put behind them the memory of their failed Agra summit of 2001. They were both strong and confident in their internal positions. Musharraf’s dual role as President and Army Chief enabled him to transcend the usual weakness handicap that civilian leaders face in Pakistan. Empowered back channels, representing strong leaders, smoothed out formal or public disagreements. Step by step efforts to reconstruct the architecture of the relationship — after the stopping of the bus, train, and air services, recall of high commissioners and 50 per cent reduction in mission strengths following the terrorist attack on our Parliament in December 2001 — gave sufficient time to sustain a sense of positive momentum. The process ended when political compulsions prevented progress, and Musharraf was weakened internally in Pakistan.

Written with an engaging flow, the book is an enjoyable read, and provides a perceptive account of the compulsions and motivations driving India’s foreign policy.

(Arun Singh is the former Indian ambassador to the US.)