The revival of a new form of constitutional liberalism can be the political glue that binds diverse social forces.

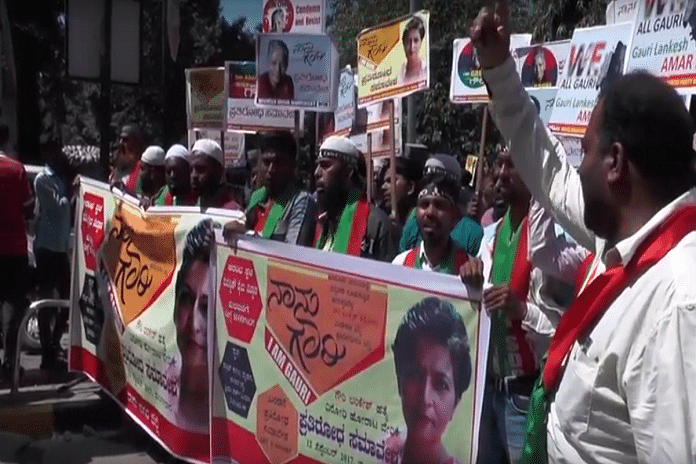

On Tuesday, 12 September, more than 10,000 people gathered in Bengaluru to condemn and protest the brutal killing of Gauri Lankesh. As the procession wound its way from the railway station to the Central College grounds, it became clear that we were witness to the largest and most diverse, voluntary non-party gathering of citizens in Bengaluru in recent memory. What brought such a large group together and can this diverse group fashion an enduring politics robust enough to counter majoritarian political mobilisation in India today?

Is there a common articulation of the political principles that could unite Lingayat pontiffs, Dalit and human rights activists, literary and film artistes, leaders of social movements and representatives of political parties? Clearly all of them had gathered out of a special affection for Gauri Lankesh, and to condemn those who killed her or celebrated her death.

The revival of a new form of constitutional liberalism and its nuanced articulation can be the political glue that binds these diverse social forces. Let’s begin by understanding the evocative power of a simple restatement of the constitutional liberal ideal and recognise its ability to direct political action and counter majoritarian trends in India today. The reason such a large number of people turned out for Tuesday’s rally is that they were disgusted and outraged by the use of organised violence to silence a free spirited and iconoclastic journalist.

However, this should not lead us to the conclusion that there is widespread popular support for the liberal right to free speech in Karnataka. In the recent ‘Politics and Society between Elections’ survey conducted in Karnataka, a majority of respondents agreed that those who refuse to stand for the national anthem, or refuse to chant ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’ or ate beef should be punished by the state. So, Karnataka is no liberal haven that supports untrammeled free speech rights. Nevertheless, there is a genuine outpouring of grief, shock and outrage at the murder of a journalist. This suggests that there is support for the basic liberal and humanistic premise that individual life is precious and that no social or religious group can justifiably extinguish life to prevent free public expression.

I suspect the articulation of liberal values in individualistic terms is likely to draw less popular support in India. However, there is a more willing embrace of the broader social goals of liberalism — namely to build a free, fair and prosperous society.

While there are several paths to achieving these goals and each nation and community may choose its own special and distinctive institutional path, liberalism grounds this pursuit in an institutional design that constrains the exercise of collective political power by protecting individual rights. This essential constitutional restraint on the exercise of majoritarian political power distinguishes a liberal political society from illiberal forms. In 1950, the framers of the Indian constitution deliberately committed us to this liberal constitutional mode of achieving the wider social and economic transformation that drove the freedom movement.

The inextricable link between the achievement of a free, fair and prosperous society and the protection of liberal freedoms maybe axiomatic to some forms of liberal political theory, but is not commonly understood by the public at large. In fact, there are several instances in our contemporary politics where we’re invited to strike a Faustian bargain: to trade our individual freedoms for our collective prosperity, a la Singapore or China. So, it is imperative to show that constitutional liberalism is not confined to postures and gestures towards freedom that excite the classroom, the television studio or the Twitterati. Instead, we need a liberal politics of action and consequence that takes our political and social conditions seriously and offers material and social progress to the most disadvantaged in Indian society. Unless constitutional liberalism can demonstrably show that it can deliver prosperity, fairness and freedom it is likely that some sections of our society will be ready to strike an ugly bargain.

It is not necessary either theoretically or practically for diverse sections of society to agree on the epistemological foundations for the embrace of these principles. As demonstrated by the wide range of actors who came together in Bengaluru: the religious, the Left and Dalit groups can all come together and espouse the constitutional liberal principle without agreeing on their reasons for accepting such a principle.

However, this large tent approach to the restatement of constitutional liberalism should constantly reiterate the core liberal commitment to the protection of life and liberty of citizens above all other political goals. Unless adherence to this core commitment is secured and constantly reiterated we will revert to an ineffective cacophony of disconnected voices who cannot hold firm when threatened by a simplistic yet unified majoritarian nationalism.

The argument that this thin idea of constitutional liberalism has the potential to anchor our politics and weave diverse groups could be attacked as another form of deracinated Western intellectualism that is neither rooted nor expressed in our political and cultural traditions. By implication, this non-native political expression stands no chance when confronted by a belligerent nativist majoritarian nationalism.

This attack misunderstands the hybrid and novel character of the constitutional liberalism that the founders of the Indian republic chose in 1950.

The Indian Constitution draws on and departs from western constitutional history and ideas to develop a uniquely Indian variety of liberalism that is worth defending with all the political resources we can command.