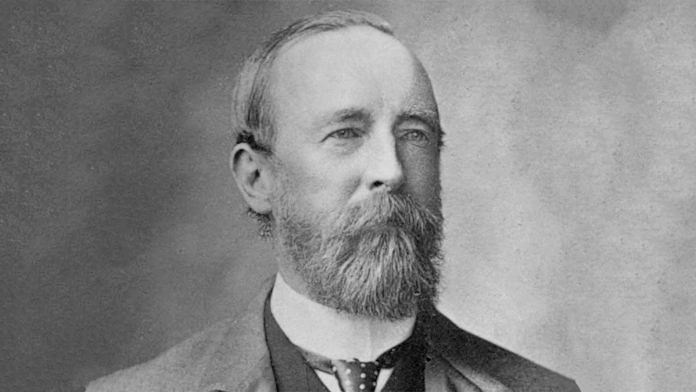

New Delhi: Almost 136 years ago, Allan Octavian Hume, a British civil servant working in India, wrote a provocative letter to the graduates of the University of Calcutta.

“If you, the picked men, the most highly educated of the nation, cannot, scorning personal ease and selfish objects, make a resolute struggle to secure greater freedom for yourselves and your country, a more impartial administration, a larger share in the management of your own affairs, then we, your friends, are wrong and our adversaries right,” wrote Hume in 1883, according to Revival: The Rise and Growth of the Congress in India by C.F. Andrews and Girija Mookerjee.

Two years later, those chosen men of India came together under the aegis of Hume to form India’s first political party — the Indian National Congress. Hume, a member of the Theosophical Society, formed the party because of the influence of the “mystic gurus of the Himalayas”, believe some historians.

But Hume was also a staunch social reformer and worked with leaders like Dadabhai Naoroji and B.M. Malabari, and served as the first general secretary of the party.

Hume’s journey

A.O. Hume was born on 6 June 1829 in Scotland’s Montrose. He came to India in 1849 as an Indian Civil Service employee and quickly rose up the ladder.

As the Sepoy mutiny — known as India’s First War of Independence — broke out in 1857, Hume commanded an irregular force of 650 troops in the Etawah region of modern-day Uttar Pradesh.

“God help the poor cowed villagers I can’t…and nobody else seems inclined to do so,” Hume is said to have written after the revolt.

“Hume never recovered from the shake-up of the revolution — the Indian people had clearly found their rulers lacking. The atrocities committed in war — not least from the British side — demonstrated that a gulf existed between the Indians and the British,” said a piece in digital magazine Madras Courier.

Hume’s criticism of the British Rule for its treatment of the natives only grew after the mutiny — he retired from the services in 1882 and formed the Indian National Congress in 1885.

“The days of despotism and bureaucracies are drawing to a close. The days of democracies are opening out. We may have to wait but we are on the winning side,” Hume is believed to have said about the Congress, according to academic J.P. Mishra.

In 1885, Hume “informed the Governor General (Lord Dufferin) that the bureaucracy was demoralised” and the colonial administration was perpetrating “gross injustice”, Mishra wrote in his book, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress.

According to Mishra, Hume fought against the racial bias of the officers and was a severe critic of “pure absolutism of a foreign official rule”.

Hume’s politics closely mirrored that of his father Joseph Hume, a radical politician who was responsible for a number of social reforms in England.

For the Congress founder, the emancipation of the Indian public was crucial — he introduced secular education in Urdu and Hindi, made agricultural reforms and improved healthcare provisions during his tenure as a civil servant.

In 1886, Hume wrote the poem Old Man’s Hope, urging Indians to make a nation for themselves.

“Are ye Serfs or are ye Freemen,

Ye that grovel in the shade?

In your own hands rest the issues!

By themselves are nations made!

Sons of Ind, be up and doing,

Let your course by none be stayed;

Lo! the Dawn is in the East;

By themselves are nations made!”

Distrust of Hume

Hume’s very vocal criticism of the British Rule earned him many detractors.

His first critic was the “Governor of Bombay, Reay, whom he had invited to preside over the first Congress session”, wrote Mishra.

“C.U. Aitchison, who was often consulted by Dufferin on political issues, described Hume’s principles as “inscrutable”,” added the academic.

An unfortunate incident with Hume’s 1886 pamphlet Rising Tide, which criticised the Viceroy, furthered this distrust among Britishers. Then, according to Mishra, newspapers like The Pioneer and The Times of India, demanded action against Hume.

“The Times of India echoing the official policy branded the leaders of the Congress as “educated agitators”. It pointed out that the Congress movement was fictitious “chiefly manipulated by one English wirepuller”,” wrote Mishra.

But it wasn’t just the British who didn’t trust Hume. The “safety valve” theory — according to which, the Congress was formed to give Indians an outlet for their resentment — also made some Indian leaders treat Hume with scepticism. One of those leaders was freedom fighter Lala Lajpat Rai.

“It has been pointed out that “an Indian National Congress with an Englishman at its head was an unnatural arrangement”. Under his influence the Congress “partook of all the characteristics of English political organisation”. It was due to such a character of the organisation that sufficient number of men did not come forward to support him,” wrote Mishra.

The increasing distrust of him among the British and the waning of his influence over the Congress pushed him to leave for England in 1892.

Of birds and books

Hume, however, was more than just a political figure and administrator. He was also an enthusiastic bird watcher and one of the pioneers of birding in India. He was an ornithologist and wrote many volumes about his experiences in List of Birds in India.

He also authored Agricultural Reform in India, among his many works, apart from writing poetry.

“Retiring to the Dulwich district of London, he participated in and financed radical political causes, serving as president of the Dulwich Liberal Association from 1894 until his death,” according to Britannica.

After founding an Indian party that has now survived 134 years, Hume died in London on 31 July 1912.

Also read: Mrinal Sen, the cinematic genius who had the courage to bring social realities on celluloid

We Indians love foreigners