What foreign investors need is certainty in tax laws and not a tax-free environment, the former President and finance minister argues to justify his controversial tax decision.

The UPA government’s decision in 2012 to change the Income Tax Act with retrospective effect is one of the most controversial taxation moves in recent times. Former President Pranab Mukherjee, who was behind the proposal as finance minister, was at the centre of this financial storm. The amendment was branded regressive and it was feared that the move would make India less attractive to foreign investors.

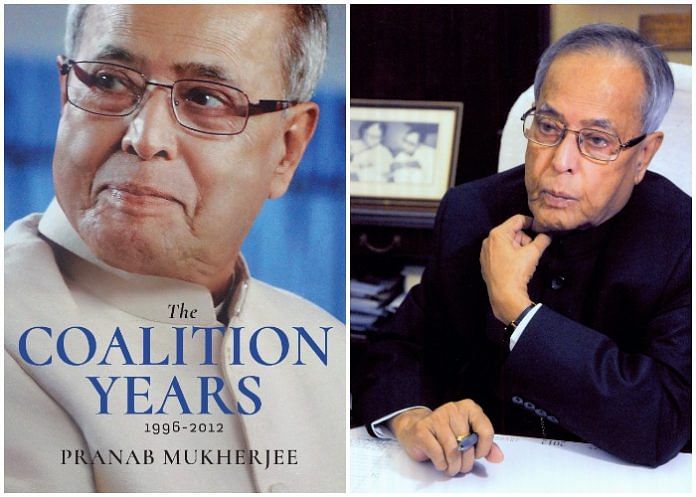

In his latest book The Coalition Years (1996 – 2012) – published by Rupa Publications and released on 13 October – Mukherjee revisits his contentious decision and reveals inside details of what went on behind the scenes in the government.

Edited Excerpts:

FDI policy is entirely the prerogative of the executive

This decision of mine, born out of my conviction that India’s Direct Tax Policy should not discriminate between domestic and foreign entities, was a subject of much debate and remains so to date. The controversy began when I announced in my 2012–13 budget speech that I proposed to amend the Income Tax Act, 1961, with retrospective effect to undo the Supreme Court judgement in the Vodafone tax case.

While the Supreme Court, in an interim order on 15 November 2011, had directed Vodafone International to pay Rs 2,500 crore and provide a bank guarantee of Rs 8,500 crore, its decision of 20 January 2012 directed the tax department to refund Rs 2,500 crore with interest of 4 per cent within two months and asked its registry to return the bank guarantee within four weeks. With the Supreme Court setting aside the judgement of the High Court, it created an unusual situation where the tax department would have to return several thousands of crores to several companies.

One of the major concerns of the Supreme Court while delivering its judgement was the potential effect on FDI. I maintain that these concerns, which might have persuaded them to give a decision against the revenue department, were unfounded. First, this was not a case of FDI. Rather, money was paid by one foreign company to another for purchasing the former’s assets in India. Second, the nature of the FDI policy is entirely the prerogative of the Executive.

Investors need certainty in tax laws, not tax-free environment

It is pertinent to note that FDI investments are not dependent upon tax; rather, crucial deciding factors include the size of the domestic market, low costs of operations and labour and skilled manpower. Competition from relatively low-tax countries without these advantages is unlikely for the location choice of FDI. Since India offers a huge domestic market, low costs of operations and a cheap and skilled workforce, a direct tax policy that does not discriminate between domestic and foreign entities has very little role to play in attracting FDI.

As a matter of policy, the source country should protect its tax base by ensuring that those foreign investors who have earned through their investments in the source country should also pay taxes like any other domestic investor or resident taxpayer. Just because some foreign investors choose to structure their investments through tax havens, they should not, as a matter of policy, get away without paying any taxes.

Also read: Dada don’t preach

What foreign investors need is certainty in tax laws and not a tax-free environment, which no emerging economy can afford. I was convinced that this certainty of payment of taxes needed to be embedded in our tax policy.

The budgetary proposal to amend the Income Tax Act with retrospective effect from 1962 to assert the government’s right to levy tax on merger and acquisition (M&A) deals involving overseas companies with business assets in India was an enabling provision to protect the fiscal interests of the country and avert the chances of a crisis. This retrospective arrangement was not merely to check the erosion of revenues in present cases, but also to prevent the outgo of revenues in old cases. As the Finance Minister, I was convinced of my duty to protect the interest of the country from the revenue point of view.

Manmohan Singh was convinced FDI inflows would be hurt

The budget proposal to undo the Supreme Court judgement evoked sharp reactions, not only domestically but also internationally. Some said that the Indian Government was ‘going back to its old socialist ways.’

[Harish] Salve was deeply critical of the United Progressive Alliance’s budget on the whole. We should show that we have institutions in this country which work. I think the country will pay a dear price for this. I think we are on course for elections this year. It’s a government which is politically rattled. They don’t want to take tough decisions and introduce reformist measures. This is waging war on foreign investment. If a client asked me ‘should I invest in India today? I would say “no”,’ he said.

Manmohan Singh was convinced that the proposed amendment in the IT Act would impact FDI inflows into the country. I explained to him that India was not a ‘no-tax’ or ‘low-tax’ country. Here all taxpayers, whether resident or non-resident, are treated equally. I insisted that as per our country’s tax laws, if you pay tax in one country, you need not pay tax in the other country of your business operation which is covered by the Double Tax Avoidance Agreement (DTAA). But it cannot be a case that you pay no tax at all. I clarified that some entities had done their tax planning in such a way that they didn’t have to pay tax at all. My intention was clear: where assets are created in one country, it will have to be taxed by that country unless it is covered by the DTAA.

Senior colleague came with Vodafone official seeking reconsideration

Later, Sonia Gandhi, Kapil Sibal and P. Chidambaram also expressed the apprehension that the retrospective amendments would create a negative sentiment for FDI. I explained to them that FDI comes when there is profitability and not on account of zero tax. Clarificatory amendments were proposed to make the intent of the legislature clear. This would bring tax certainty and would clarify that India had the right to tax similar transactions. Two more Cabinet colleagues separately advised me to take a middle path, and to reconsider the decision. But I remained resolute.

Days ahead of introducing the Finance Bill in Parliament 2012, several colleagues, including one along with a high-ranking Vodafone official, approached me seeking reconsideration of the move to retrospectively amend laws.

No FM after me has repealed retrospective tax

Despite the angst that my proposal generated at that time, and even now, both from within my party and outside, I wonder why every succeeding finance minister in the past five years has maintained the same stance.