The past few weeks have seen some outcry and a petition against the controversial move of the Narendra Modi government to restructure the National Archives of India under the Central Vista Project. Some commentators are of the view that the change is merely a physical relocation of the records. Others are mobilising their resources to protest through professional associations and personal connections. A recent response to these protests in these very pages has taken a critical view of what the author interprets as a liberal “victimhood syndrome”. Additionally, the author’s reading of this new wave of archive activism muddles the aforementioned liberal politics with an appraisal of the handling of historical records.

Yet, the author’s inflammatory charge of “intellectual laziness” on the part of Indian liberalism offers the right provocation for teasing out two important conversations around the future of Indian archives — the public debate on the physical safety of the archive and the academic debate on recovering political traditions via historical records. Both these debates hinge on anxieties regarding archives, but they are separate, and it is not necessary that all those who feel anxious on one account feel that way on both.

The operational anxiety

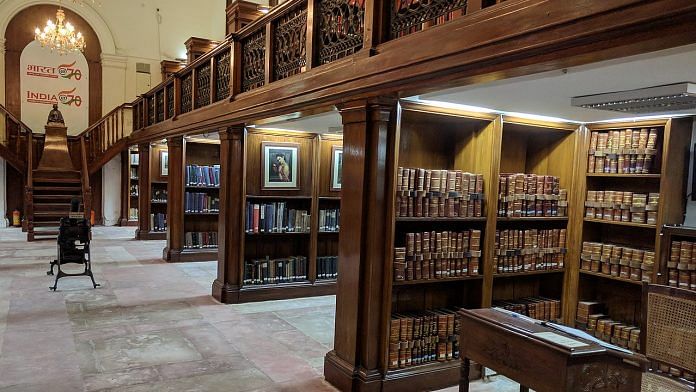

The first anxiety, a more publicly visible lament, is as much about the state of the archives as they were before the proposed changes as it is about their surviving the relocation. Successive governments have failed to address the systemic issues that have plagued archives in India. Even in the blatant neglect they face, archives follow the Centre-state hierarchy – the state archives are much worse off than the national archives ever were. The lack of basic infrastructure, the lethargic digitisation of records but also absence of facilities for scholars to digitise the files they need, restrictions on photography, a totally dysfunctional photocopying system that relies on support staff who are completely overwhelmed by demands on their time and mostly impervious to the enormous significance of the material they are handling, and the literal widespread rot in the form of all kinds of physical and animal residue on the files are some of the problems facing the National Archives of India.

These problems are easily fixed, as is evident from the way the manuscripts section of the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (Teen Murti, as it’s popularly known) is run. These two institutions are the first ports of call for any historian working on India, and the contrast between them could not be more stark. Although Teen Murti may not be exemplary in this regard, it can at least be instructional in how an archive can be successfully managed under specifically Indian circumstances. Given the sheer volume of textual records held at these institutions, they are repositories of the records of independent India, the British colonial period (and by extension, the British Empire), and the pre-colonial period, although that is an entirely inadequate term to describe the vast holdings of the National Archives of India.

Also read: These 12 landmark buildings will be demolished for Modi govt’s Rs 20K cr Central Vista project

The academic anxiety

The second anxiety, a largely academic one, is to do with critical histories of India, and a long overdue, scrutiny of sources and methods. Subversive, combative histories are being written in the current moment on Indian political thought, anti-imperial imagination and historical agency. These histories of ideas, discourses and narratives unite in them questions of legitimacy and State action, no matter the political party in power, but with a keen eye to electoral politics, the features of particular ideologies and processes of exclusion and oppression. In the absence of archives, the fear is that in our understanding of our past, we may produce work that is not only ahistorical, but also possibly anti-historical.

The role of archival material, and the writing up of said material is to thwart attempts at what American commentator Reinhold Niebuhr has called “managing history”. In that same vein, radical political action is also possible and often accompanies the project to widen and deepen the histories we write through the archives we read. Thus, if that may be a personal political choice, then it is entirely possible to agitate against the loss of an archive while holding the position that Hindutva politics does not deserve any legitimacy.

I take exception, therefore, to silencing this critique as housing some sort of parochialism. The odd and excessive hinging on Nehru’s historical method, whatever that may be, is not helpful at all as an analysis. Nehru often wrote in a historical register, yes, but his historical sensibility and its lapses should be the object of historical examination, not his method. The trope of liberals and their triumphalism and/or victimhood, and any charges of partisanship, both from the left and the right, are also, in fact, of very limited use and unfortunately, stem from the assumption that one is approaching the archives from a primordially political locus standi.

The more pressing question is — what is the future of Indian archives now? If plans for the future of the files is undisclosed, or worse, undecided, could the catalogues at least be digitised and made available? Could a team of historians be handed this responsibility? What are the implications of these changes on India’s historiography? How will historians offer any diagnosis of the roots of the present if they are not allowed democratic and full access to the past?

The writing of a nation’s history has deep connections to its resilience as a political entity. The nation asserts its competing identities through contested histories. The illusion that an archive exists, but that its exact form or location cannot be at this point ascertained is an exercise of power by the State. This erasure cannot and should not be conceded. The institution that has long been a keeper of the nation’s history is now under duress and needs active and persistent petitioning for answers. It is poetic justice that the National Archives of India is situated at the intersection of Janpath (People’s Path) and Rajpath (King’s Way). After all, it is the historical archive that is called upon when the government record is at cross purposes with the people’s history.

Swapna Kona Nayudu works on India’s international relations and political thought at Harvard University Asia Center, and tweets @konanayudu. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)