If we look on the bright side of the past two years, Covid should at least mean we’ll be ready for the next major threat from infectious disease. We know how to prepare, we have more advanced technology, we’ve strengthened public-health protocols. And governments have learned just how quickly science can move when offered the right incentives.

All of these learnings are needed already — in the fight against growing antimicrobial resistance (AMR), or infections that don’t respond to drugs.

Antimicrobials is the catch-all term for the many antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals and other drugs that prevent infections in humans, animals and plants. Pathogens naturally develop resistance to antimicrobials as they evolve, but thanks to an overuse of antibiotics and other conditions, the speed of such resistance has become a major global health issue.

Common ailments such as urinary-tract infections, sexually transmitted diseases and sepsis are increasingly able to tough out the drugs developed against them. Some infections develop into superbugs that defy treatment. They cost lives and also impose huge costs on health-care systems and broader economies.

Even at a time when we’re all a bit saturated with health risk news, it’s hard to overstate the urgency of the challenge. Covid-19 has resulted in some 5.6 million deaths, but previous estimates have said AMR will claim 10 million lives annually by 2050 — and that figure already looks low. So much of modern medicine — from surgeries to chemotherapy and organ transplants — requires effective antibiotics. And now there are concerns that hospitalizations from Covid-19 have led to further overuse of antibiotics, which could increase drug resistance.

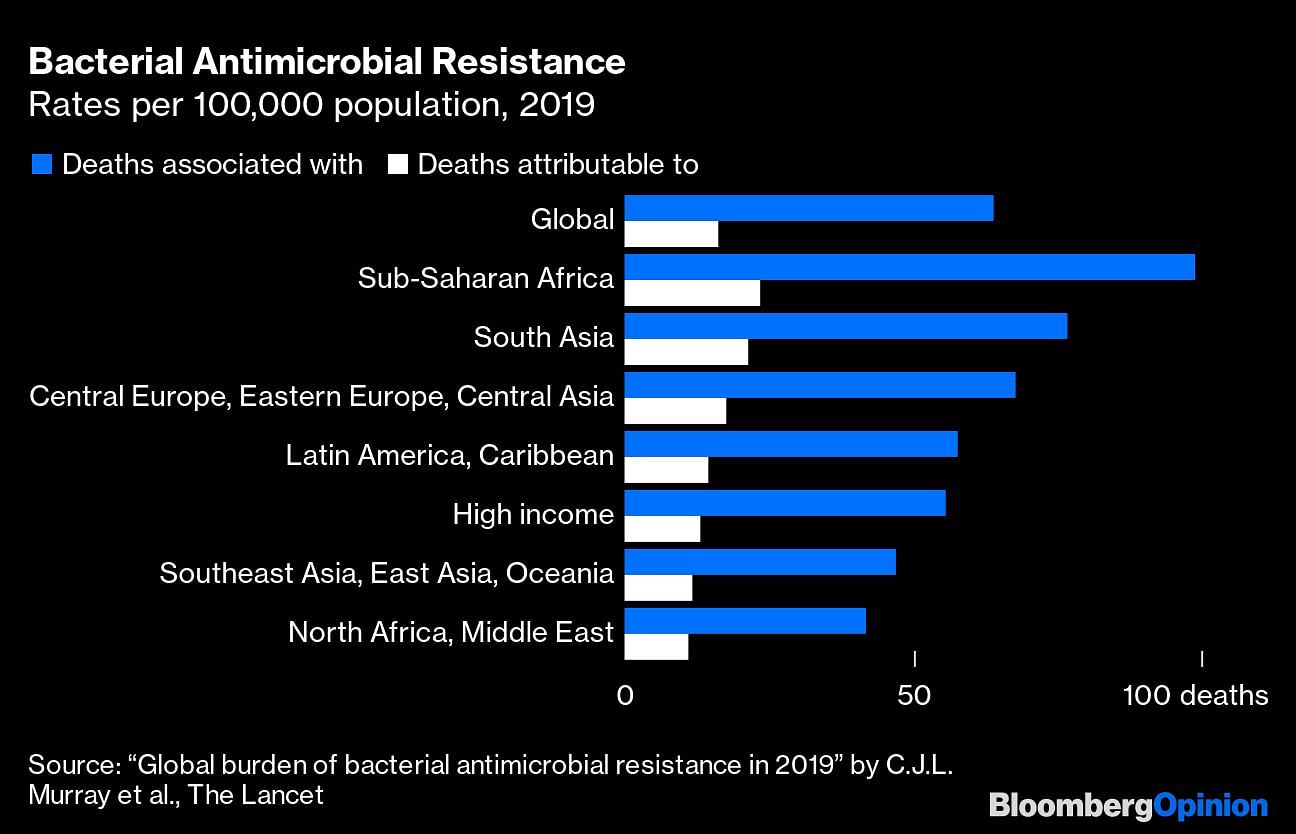

Drug-resistant infections are already killing more people globally than malaria and HIV combined. Though concentrated in low-income countries, the problem is by no means confined there. In the U.S., there are some 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections annually and over 35,000 people die as a result. Resistance to Escherichia coli (E. coli), which causes kidney infections, and Staphylococcus aureus (or staph), which is often picked up in hospitals and the cause of blood infections, has reached high levels around the world.

The more drug-resistant pathogens become, the more they will spread, making ordinary infections potentially deadly and compromising the success of advances in surgery and cancer therapy.

A new study published last week in the Lancet presents the first global estimates of the burden of antimicrobial resistance — and they confirm the worst fears. The authors estimate that in 2019, nearly 1.3 million deaths were directly attributed to infections that were drug-resistant and more than 4.9 million deaths were associated with drug resistance. One in five AMR deaths occurred in a child under the age of five.

The vast majority of the deaths, nearly 79%, were attributed to three syndromes: lower respiratory and thorax infections, bloodstream infections and intra-abdominal infections. Six pathogens were responsible for more than a quarter-million deaths globally.

Also read: US study on drug resistance says it led to 1.27 million deaths in 2019, more than HIV/AIDS

It’s hard to imagine these numbers shrinking without immediate intervention. Better education, sanitation, surveillance and innovation in diagnostics are all urgent — and our experience with Covid should help us in all of these areas. If fewer people get infections in the first place, fewer antibiotics are needed and there’s a lower prospect for drug-resistance. But new drugs also need to be part of the solution, and that will take nudges from governments to turbo-charge both innovation and launches.

While there are science challenges here too, it’s the warped incentives when it comes to developing commercializing new drugs that explain why there have been no truly new antibiotics in the past 30 years.

Drugs are commercially successful if pharma companies can make enough money on them to recoup their development. But the cost of developing an antibiotic has been estimated at around $1.5 billion, while average revenue is estimated at around $46 million a year. (By one estimate cited in Nature, a new antibiotic needs to make at least $300 million a year to keep going). Indeed, the net present value of a new arthritis drug is estimated at $1 billion at discovery, while a new antibiotic can often deliver negative value to the developer or a modest value of up to $37 million, according to one study.

An ironic twist is that doctors are discouraged from prescribing new antibiotics unless absolutely necessary (to cut down on AMR), and this drives down sales and discourages investment. The price of new antibiotics also looks uncompetitive when compared to existing generics.

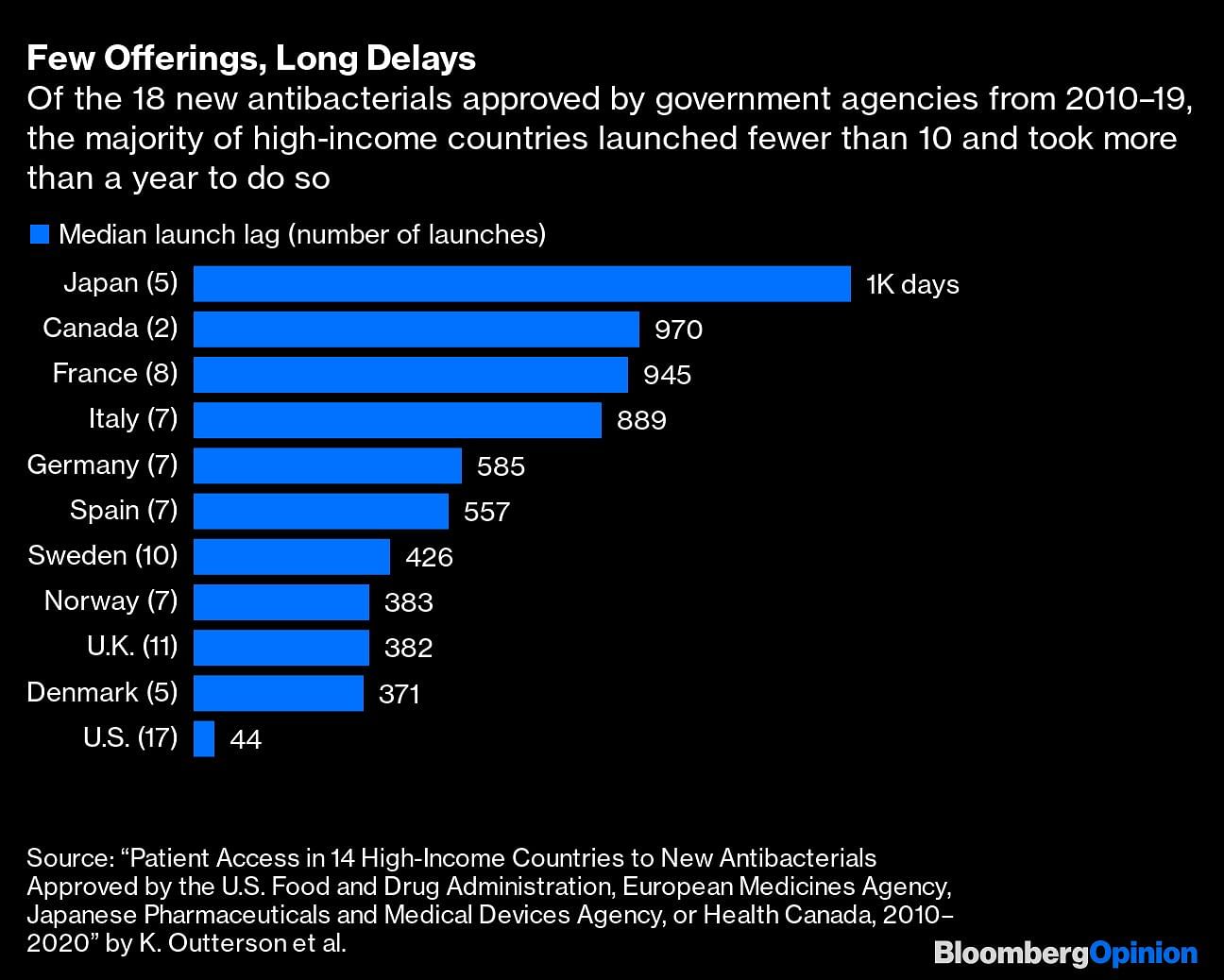

Of 15 new antibiotics that earned FDA approval in the decade to 2020, five were shelved as companies applied for bankruptcy or were sold. Researchers last year noted that while 18 antibacterials had been approved and launched in the G7 and other high-income European countries between 2010 and 2020, the majority were accessible in only three nations — Britain, the U.S. and Sweden. There are also often long delays before a drug is launched.

Many companies have decided to delay or give up commercialization altogether, especially considering oncology and other areas provide incomparably higher returns. Switzerland’s Novartis AG pulled the plug on its antibiotics research in 2018, saying it preferred to focus on cancer treatment. France’s Sanofi and the U.K.’s AstraZeneca Plc have as well.

The OECD estimated in 2017 that it would take an extra $500 million per year over 10 years to bring to market four new first-in-class antibiotics in the next 10 years. A major U.K. government report in 2016 led by former Goldman Sachs chief economist Jim O’Neill concluded that it would cost $16 billion to overhaul the antibiotic pipeline to bring 15 new antibiotics to market over the next decade.

Given the poor market incentives, a problem on this scale requires a coordinated multilateral approach. “How many decades of work went into mRNA vaccines; how many scientists around the world, how much money from governments? This wasn’t a miracle; it was built on clever funding,” says Kevin Outterson, a law professor at Boston University and the executive director of CARB-X, a non-profit that is a major investor in antimicrobials. “With vaccine development, the U.S. government took all the commercial questions off the table.” Antimicrobials deserve similar and with a better funding model, investors will come too, he says.

A combination of what health economists call push incentives and pull incentives are needed. Governments could offer push incentives — tax credits or direct R&D funding — to subsidize developments costs, as well as pull incentives, which reward companies that make it through regulatory approval and launch products.

The challenge is designing a system that ensures access to medicines without encouraging overprescription. Slowly, a number of countries are trying to address the issue. A U.K. pilot program pays companies for antimicrobials on a subscription basis, not on volumes used. (It’s referred to as a Netflix model.) In the U.S., the bipartisan Pasteur Act also uses a “delinking” system to fund subscription contracts. But the U.K. pilot is too limited at present to incentivize new development, and the U.S. legislation has yet to pass Congress. France, Germany and Sweden all have initiatives too, but a more coordinated approach is missing.

There may be glimmers of hope on the scientific front. Earlier this week, a group of Australian scientists said they found a way to defeat superbugs that had developed a resistance to antibiotics. Their approach was using treatments combining nanoparticles (ultrafine particles) with antibiotics. The use of nanotechnology to reduce the dose of antibiotics could help reduce the need for new antibiotic treatments, the authors said.

The pandemic has taught us about the high cost of delayed action to global health crises — as well as the enormous gains to be made when governments ensure that scientific innovation is incentivized. Our next test is to see whether we can remember those lessons.—Bloomberg

Also read: World has taken over 10 billion Covid vaccine doses, rich nations used 71%: Bloomberg tracker