As rivers and taps run dry, trouble is brewing over hydroelectric projects India is building along the Chenab River that Pakistan says will impact its water supply.

As rivers and taps run dry, water has the potential to become a major flash point between arch-rivals India and Pakistan.

Women and children walk miles each day in search for water in a crowded, downtrodden district of Pakistan’s financial capital, Karachi — a scene repeated in cities throughout the country.

Across the border in India, government research indicates about three-quarters of people don’t have drinking water at home and 70 percent of the country’s water is contaminated.

As rivers and taps run dry, water has the potential to become a major flash point between arch-rivals India and Pakistan. Both have repeatedly accused each other of violating the World Bank-brokered 1960s Indus Waters Treaty that ensures shared management of the six rivers crossing between the two neighbors, which have fought three major wars in the past 71 years.

The latest dispute is over hydroelectric projects India is building along the Chenab River that Pakistan says violate the treaty and will impact its water supply. Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan is sending inspectors to visit the site on Jan. 27. Indian leader Narendra Modi — who faces elections in the next few months — has vowed to proceed with construction, and it remains unclear how the impasse will be resolved.

“Tensions over water will undoubtedly intensify and put the Indus Waters Treaty — which to this point has helped ensure that they have never fought a war over water — to its greatest test,” Michael Kugelman, a senior associate for South Asia at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington said by email.

“The prospect of two nuclear-armed rivals becoming enmeshed in increasing tensions over a critical resource like water is unsettling and poses highly troubling implications for security in South Asia and the world on the whole,” he said.

For now, relations between India and Pakistan appear to be stable, and even looking more positive. Khan’s six-month-old Pakistani government has sought to mend ties with India, and has said the country’s powerful military supports those efforts — a notion greeted with skepticism in New Delhi.

Still, all sides see the long-term risks of a conflict over water: Khan himself is attempting to raise $17 billion via the world’s largest crowd fund for the construction of two large dams, one of which would be built in the disputed territory of Kashmir. In a region that’s home to about a quarter of the world’s population, failure to manage water shortages could be catastrophic.

“Any future war that happens will be on these issues,” Major General Asif Ghafoor, Pakistan’s military spokesman, told reporters last year, referring to water issues. “We need to give it a lot of attention.”

The most serious threat to the water agreement of late followed a terrorist attack on an Indian army camp in September 2016, when Modi stated that “blood and water and cannot flow together” and vowed to review the treaty.

If Modi is re-elected “there’s a possibility that water may become a tool to try bring Pakistan to heel,” said Ashok Swain, professor of peace and conflict research and the director of research at the School of International Water Cooperation at Uppsala University in Sweden.

“He may not do something immediately after resuming power but if relations with Pakistan deteriorate, by 2020-21, it’s a possibility,” Swain said. And although Pakistan’s new political leaders are aware the two dams being built by India are only one part its problem, “a water conflict with India can be a good way to hide their own mismanagement.”India’s Ministry of Water spokesman Sudhir Pandey didn’t respond to phone calls, while Pakistan’s Commissioner for Indus Waters Syed Muhammad Mehar Ali Shah was unavailable to comment.

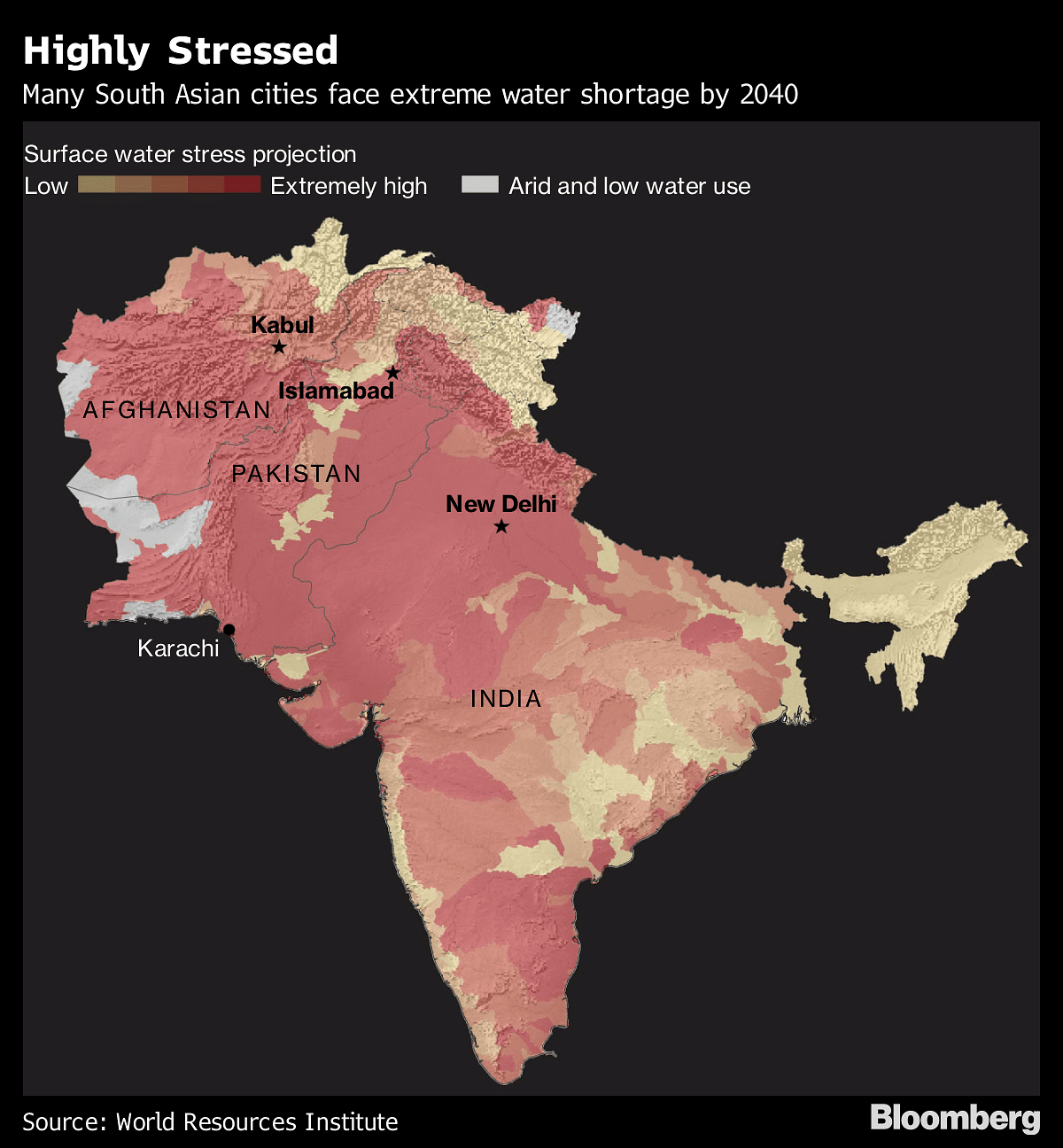

Pakistan, India and Afghanistan are among the world’s eight most water stressed countries. Waiting for hours or going days without water supply is the new normal in some crowded South Asian cities. The Indus river, one of Asia’s longest that originates in the Tibetan Plateau and flows into the Arabian sea near Karachi, has shriveled to a shadow of its former self. Water scarcity has led to regular protests in cities from Shimla in India to Lahore in Pakistan.

Most South Asian nations are heavily dependent on agriculture that consumes the majority of fresh water supply. Rice and sugarcane are grown by flooding the entire area with more than four feet of water. About 60 percent of households in India rely on agriculture while about half of Pakistan’s labor force is employed by the industry.

“South Asia has a water crisis,” said Pervaiz Amir, a regional expert for the Stockholm-based Global Water Partnership, pointing to the cities of Karachi and India’s capital, New Delhi. “You immediately start a ripple effect, first it is poverty that will increase. In the southern areas of Pakistan, extremism and terrorism will increase.”

Global agencies have made dire predictions that Pakistan — despite having the world’s largest glaciers — will face mass water scarcity by 2025. Already availability per capita has dropped by a third since 1991 to 1,017 cubic meters, according to the International Monetary Fund.

In most areas of Karachi flowing piped water is a rarity and its more than 15 million residents receive less than half of their daily needs. Even when it is supplied in the densely populated district of Lyari it only reaches a handful of houses through a leaking line that passes through mounds of garbage and leaves it smelling of sewage.

“When water comes, women come from far, far away to fill water,” said 30-year-old fisherman Abdul Qadir, pointing out dilapidated pipelines in Lyari’s Khadda Market area. “There is a line of more than 200 people here.”

Last year a judicial report showed that 91 percent of Karachi’s water was unsafe to drink. Pakistan’s poorest urban dwellers have access to only 10 liters per capita — just one fifth of the requirement, according to James Wescoat, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The World Economic Forum rates the water crisis as the biggest risk in Pakistan, with terrorist attacks third on the list. Waseem Akhtar, Karachi’s mayor, told Bloomberg the city needs to fix widespread leakages and theft, but funding is scarce.

Neighboring India’s water demand is projected to be twice the available supply by 2030 and will lead to a six percent loss in the country’s economic growth by 2050, according to the New Delhi-based government think-tank NITI Aayog.

While a solution will need regional cooperation, there’s been little coordination between India and Pakistan apart from their decades-old river-sharing agreement. Still, officials on both sides of the border recognize they need to act with urgency.

“We have a near crisis,” said S. Massod Hussain, chairman of India’s central water commission. “We need better management of our water resources.”-Bloomberg

Upcoming Water Crisis in Pakistan

Pakistan is not only financially stressed, militarily stressed, but a dangerous water shortage is on the horizon. Inside five years, there likely is either rationed drinking water or agriculture will receive lesser water resulting in lower food production.

Pakistani Punjab has four rivers crisis-crossing its land mass. Monsoon rains are in abundance, except during El-Nino year. Also rivers are fed by glaciers melt, hence water has been all year around and in abundance. That had been true for the last many millennia. Now comes the human intervention of the last 60 years – the Global Warming is affecting the Monsoon pattern, like this year these are erratic but still in abundance. The Global Warming is also melting away the glaciers which feed the rivers. Initially the flow increased, but as the glaciers melt away the water flow has decreased, as much as 50%. These two are the half the problems which Pakistan is facing. The others are the inefficient use of water and design of canals which irrigate the grain fields.

These canals were built by the British in the late eighteen hundreds. They found the excellent top soil and flat topography to build canals. These canals were built from west to east, hence the water of the Jhelum River will irrigate land to the east right up to Chenab River and the water of Chenab will irrigate land to the east all the way to Ravi River etc. There was a deliberate scheme in the British mind. They did not wish to hand over control of River and canal water to the local governments. They wished people to the east be dependent on water immediately to the west, least one day the locals grab the water as well as canals, the rivers and declare themselves independent. The British kept the capability to turn off the water flow from the river immediately to the west. Had it been the other way around then at any given time they could have faced a nearly independent farm economy and a state. Water flow kept the control in their hands.

These canals were built with 1800s technology, hence were not lined letting more than half the water to seepage during its flow to the farms. Since water was in abundance, nobody thought about the seepage issue at all, even after the British left. Today 85% of available water in Pakistani Punjab is used for agriculture, of which 55% is lost in seepage. Remaining 15% is used for domestic, industrial and construction purposes.

Since after the signing of Indus Water Treaty in the early sixties, Pakistan was allowed to build storage capacities to store excess water for the dry season. This they did not do, as much of the cash was spent on military and other useless ventures like intervention in Afghanistan, hence capability to store surplus water was ignored. This was not a serious issue until global warming melted away the glaciers which were feeding the rivers, hence the river water flow declined to half to what it was in early to mid nineteen hundreds.

Now the water scarcity problems of today.

In fact, Pakistan has no abundant water storage capacity, except two large dams. Also, it has the most inefficient canal systems feeding the agricultural land and bad….. bad management for the available water. Rising population has put a huge pressure on domestic use water. If it was one season or two due to the failure of rains, it is understandable. But it is not, if it is bad management.

Compared to that Indian Punjab have newly built dams, canals (all partially lined to prevent seepage) and can store water for 100 days as opposed to just 15 days in Pakistani Punjab. …… what a contrast. Before partition, the Pakistani Punjab was twice more prosperous than Indian Punjab. Now it is the other way around. Monsoon vagaries affect both Punjab the same way, hence other than bad management, there is no other reason for the decline of Pakistani Punjab.

What can be done?

That excessive emphasis on Military in Pakistan has to stop. Even if the World Bank or India or China extend their helping hand to fix the problem, that hidden hand of the Pakistani military to grab the money will have to be removed, rather the military has to be confined to the barracks. The economy will have to play a dominant role with civilian authority in charge. They should copy the Indian model to build dams on the rivers for water storage and power generation. India has built or building three dams on River Chenab to store water and generate power. Pakistan has none in 800km run of the river thru Pakistani Punjab. Their focus is about picking up a fight on water issues with negative results and themselves do nothing.

Time is fast passing and thirsty and hungry people will be running around in search of food and water and create another refugee problem for somebody else to come and fix it. Hence, begin now or wait for the people to swallow you in a revolution. The key is to begin with downsizing the military and remove them power. Make Kashmir as a non issue and learn from India. In five years time, India will be $5 trillion economy. Pakistan will be stuck at the low end on the economic scale.

God bless the people of Pakistan and help them remove military from the power equation.

Real journalism. Well researched. The world needs to know this. Immediate next steps could be doing R&D on better methods to filter and purify water. One example is point of use purification rather than bottled water. Such technologies tend to be ineffective toys. However, the science and tools exist so that really good, cost effective, and safe devices could be developed, with reasonable effort.

Very well written ,an eye opening and honest assessment, It’s time to forget Kashmir and think about the future and human race survival,Stop developing weapons, pay attention to basic human needs. Its a shame that in both countries the poor are suffering, in both countries, the poor needs water, toilets , Education and all other basic human needs.